by Emrys Westacott

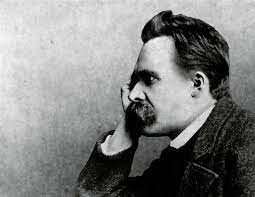

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

But why? It certainly isn’t because he’s the thinker I agree with most. In fact there are many aspects of his thought that are silly, hopelessly outmoded, or morally objectionable. Some of his observations about women, about racial types, about democracy, and about liberal values in general, for instance, are about as misguided as its possible to be––at least from the standpoint of anyone who endorses said liberal values. His unabashed elitism, and occasional apparent indifference to the suffering so often inflicted on the many by the powerful few, would be almost laughable if it weren’t for the fact that we still live in a world were such suffering abounds.

Finding examples in Nietzsche’s writings of propositions that are awful-going-on-horrible is like looking for a needle in a tin of needles. On women, for instance:

When a woman has scholarly intentions there is usually something wrong with her sexually.[1]

On how the ruling class may and should treat those beneath them:

The essential characteristic of a good and healthy aristocracy …is that it experiences itself not as a function (whether of the monarchy or the commonwealth) but as their meaning and highest justification–that it therefore accepts with a good conscience the sacrifice of untold human beings who, for its sake, must be reduced and lowered to incomplete human beings, to slaves, to instruments.[2]

Or on what constitutes progress:

The magnitude of an “advance” can… be measured by the mass of things that had to be sacrificed to it; mankind in the mass sacrificed to the prosperity of a single stronger species of man–that would be an advance.[3]

Given such sentiments, why on earth do I like Nietzsche so much? After all, I like most of Nietzsche readers–and today he is probably the most popular of the “great” philosophers–would almost certainly be judged by him to be “herd” or “rabble,” self-interestedly promoting the values of what he calls “the last man”–viz. safety, comfort, contentment, and mediocrity. Read more »

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed. The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.

The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.

Early in the story of

Early in the story of

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows.

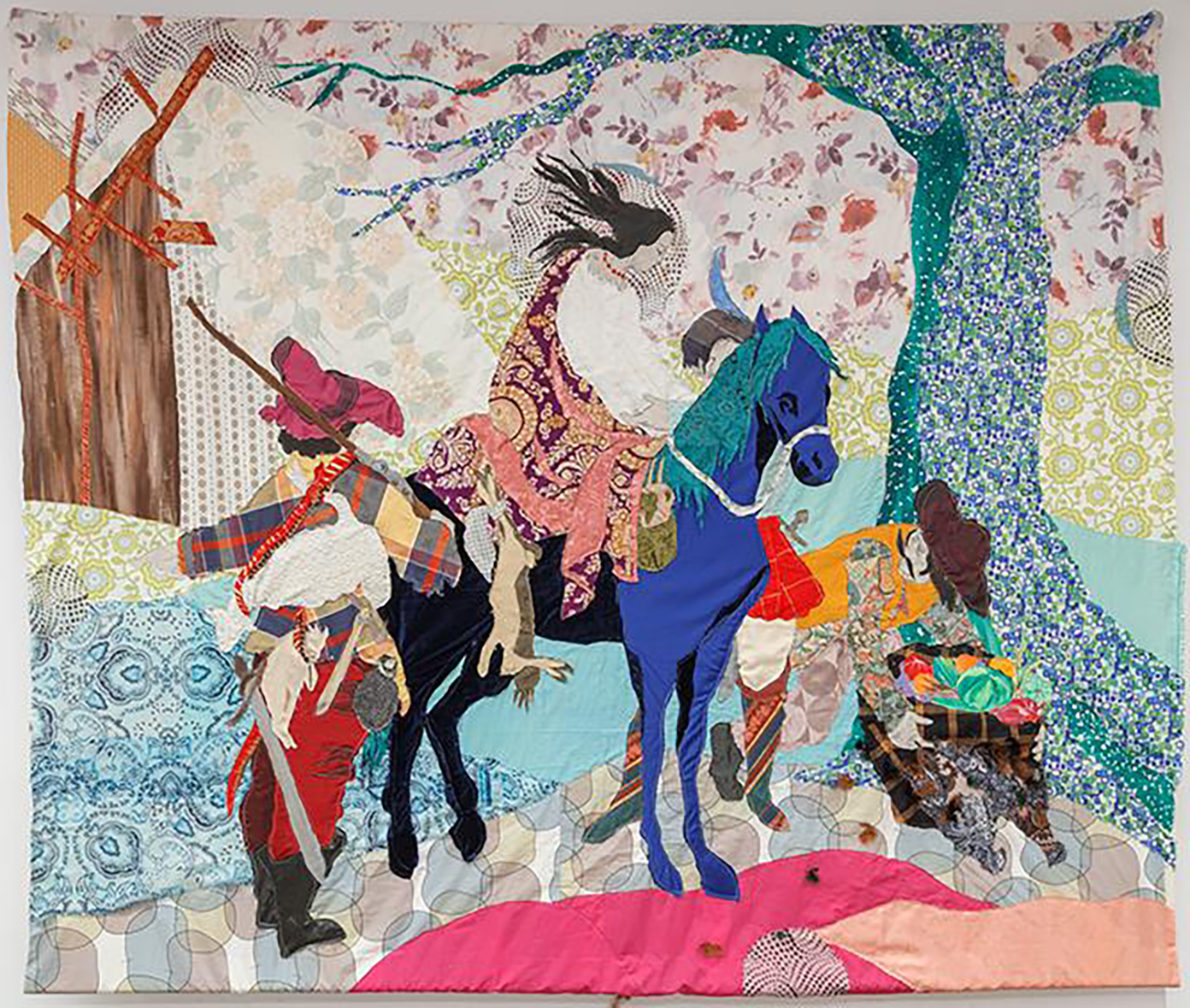

You’ve heard the story before. The poet Orpheus, celebrated for the enchanting quality of his voice, is grieving the sudden death of his young wife Eurydice. In his despair he resolves to harrow the Underworld, where he so impresses the god Hades with his singing that he is permitted to retrieve the shade of his bride and return with her, newly embodied, into the light—on one condition: that he not look back at Eurydice until they have attained the realm of the living. All is proceeding according to plan, and the pair have nearly made it to the world above, when Orpheus, overcome by the suspicion that he has been swindled, turns to assure himself that his silent wife is still following him—only to see her flee away, this time forever, back into the shadows. Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Out of Egypt. 2021

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Out of Egypt. 2021 Death was already about me. I’d recently written two death songs. Not mournful, but peaceful and welcoming. No reason. They just seeped out of me. Then came the Covid infection. It must’ve found me in upstate New York while vacationing with friends.

Death was already about me. I’d recently written two death songs. Not mournful, but peaceful and welcoming. No reason. They just seeped out of me. Then came the Covid infection. It must’ve found me in upstate New York while vacationing with friends.