by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Bill Murray

I

Russia’s war on Ukraine is realigning geopolitics everywhere you look. The Germans and French want the conflict to end immediately. Others won’t be heartbroken to see fighting continue to degrade Russian capabilities. The UK, Poles and Balts come to mind here. An idea is settling in that the US, too, doesn’t entirely mind fighting Russia to the last Ukrainian. There’s no denying the war is less painful from forty five hundred miles away.

Look north and if Finland and Sweden join NATO, overnight the Baltic Sea becomes the beating heart of European security. The shallow, enclosed Baltic hasn’t played such a heady role since the days of Napoleon. Vilnius and Riga never dreamed of such proximity to power.

In 2019 Mikhail Saakashvili, a previous victim of Russian aggression, predicted Russia’s next attack would come against Finland or Sweden. He was wrong, but he might not be wrong forever. That’s the fear that fuels an astonishing rush toward strategic realignment around the Baltic Sea.

Finnish President Sauli Niinistö is two years shy of wrapping up his second six year term. The 73 year old son of a newspaperman and a nurse from Finland’s southwest coast, Niinistö consistently polls as the country’s most revered figure.

He was in Washington a week and a day after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, already working to insure the American administration’s blessing for Finland’s accession to NATO. The Finns hold their president in such regard that his backing of Finland’s coming NATO application should insure the peoples’ approval.

Niinistö put it this way: “Sufficient security is where Finns can feel that there is no emergency and there won’t be one.” Joining NATO, he said, would be “most sufficient.” Read more »

by R. Passov

After Steve Jobs hit his VP of development on the forehead, called him a stupid fuck, then stormed out of a meeting that had been set up to see George’s invention, everything changed.

The invention, George said, was on the motherboard. Dell and HP were buying 40 million so that no matter where you were in the world you could grab the local, over-the-air broadcast signal and with a little software, read the signal by the hardware, turning your computer into a TV.

By 2005, Jobs didn’t want anyone reaching out over the air. He wanted everyone to come through the Apple store. Apparently, neither his VP of development or George knew that. On its way toward bankruptcy, CrestaTech ate a fortune.

* * *

Back in the early 1990’s, before one of Sun Microsystems frequent purges forced me out, I shared an office with George and a fellow named Hung Gee. I came to understand something of what George labored on; learning the arc of his career from Daisy Systems – an innovator in microchip design tools – through to Sun where he managed a small corner of the Scalable Processor Architecture or SPARC Chip. As the geometry of microprocessors shrank, electrons traveled shorter distances. The non-intuitive result was to ask less of the hardware (the microprocessor) and more of the software.

Hung Gee was harder to pierce. George believes he can trace Hong Gee’s path to the parking lot of MIPS, another architectural innovator, and to the day in that parking lot when a man with the same name as Hong Gee shot his boss.

What is the blues? It is a mood, a feeling, a sensibility. Feeling blue. Feeling blue?

It is a musical form, existing in its own tradition, but also as a form within the jazz tradition. The latter is what this series article is about, the blues as it functions within the evolving context of jazz.

The blues is also an object of wonder, fascination, and mystery. Back in the middle of the 20th century some curious and well-meaning white folks went looking for the blues. Marybeth Hamilton wrote a book about their quest, In Search of the Blues:

Leadbelly, Robert Johnson, Charley Patton-we are all familiar with the story of the Delta blues. Fierce, raw voices; tormented drifters; deals with the devil at the crossroads at midnight.

In this extraordinary reconstruction of the origins of the Delta blues, historian Marybeth Hamilton demonstrates that the story as we know it is largely a myth. The idea of something called Delta blues only emerged in the mid-twentieth century, the culmination of a longstanding white fascination with the exotic mysteries of black music.

Hamilton shows that the Delta blues was effectively invented by white pilgrims, seekers, and propagandists who headed deep into America’s south in search of an authentic black voice of rage and redemption. In their quest, and in the immense popularity of the music they championed, we confront America’s ongoing love affair with racial difference.

That’s from the publisher’s blurb. It sounds about right, though I’ve not read the book. I’ve read other books. I know a thing or two. In 1966 a man named Charlie Keil published Urban Blues. It blew the doors off that myth. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Gérard Roland came to Berkeley only around the turn of this century. He grew up in Belgium, was a radical student, and after the student movements of Europe subsided, he supported himself for a time by operating trams in the city. When he was wooing his girlfriend (later wife), Heddy, she used to get a free ride in his trams. (A few years back when I visited them one summer in their villa in the Italian countryside near Lucca, Heddy told me in jest that those days she was content with a free tram ride, but now she needed a house in Tuscany to be placated). Gérard is also a good cook.

Gérard Roland came to Berkeley only around the turn of this century. He grew up in Belgium, was a radical student, and after the student movements of Europe subsided, he supported himself for a time by operating trams in the city. When he was wooing his girlfriend (later wife), Heddy, she used to get a free ride in his trams. (A few years back when I visited them one summer in their villa in the Italian countryside near Lucca, Heddy told me in jest that those days she was content with a free tram ride, but now she needed a house in Tuscany to be placated). Gérard is also a good cook.

As with Andreu, my special link with Gérard was based on our shared interests in history, politics and culture. In addition, his research involves analyzing institutional rules in the economic development process and issues of comparative economic systems, which have also been part of my own research themes. He comes to this set of issues from his long-run interest in Russia in its process of economic transition after the fall of Berlin wall, and later in China.

At this point I might as well give some perspective for my interest in institutional and comparative-systemic issues in the context of the subsequent developments in the discipline of Economics. By institutions economists do not necessarily mean an establishment or organization. They apply the term to imply general rules and practice and custom in economic arrangements. I have earlier talked about my interest in and detailed empirical work on agrarian relations in Indian villages—these relations are often examples of small-scale economic institutions at the micro-level. Thus sharecropping, that my early work was concerned with, is a prime example of an age-old economic institutional arrangement. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

The New York Times’ columnist who thought that a good way to capture the interconnectedness of the modern world was to say that “The World is Flat” – an idea, arguably, better captured by saying that the world is round (which it is) – recently joined the chorus of pundits saying, yeah, Putin started the war in the Ukraine, but the U.S. is also to blame – or at least, “America is not entirely innocent of fueling [Putin’s] fires.”

Former Kremlin advisor Sergey Karaganov has been widely quoted (more quoted, than vetted, I think) as saying “For 25 years, people like myself have been saying that if NATO and Western alliance’s expand beyond certain red lines, especially into Ukraine, there will be a war. I envisioned that scenario as far back as 1997.” Envisioned, maybe, is not the right word. As an influential advisor to Putin, it seems he advised Putin that destroying the Ukraine was necessary to prevent NATO expansion. In an interesting turn of phrase Karaganov now says that what Russia “needs is a kind of solution which would be called peace.” Which would be called peace? Right. That doesn’t sound ominous, at all.

There are plenty of other examples of the argument that the West, the U.S., and/or NATO, share blame for the war for not making clear that they would never, ever going allow the Ukraine to join NATO – even if that would have been good for both parties (absent Russian aggression). What if anything is wrong with this style of argument? Scholars and theorists of foreign affairs call the view represented “realism”. Personally, I’m against it. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Scientists like to think that they are objective and unbiased, driven by hard facts and evidence-based inquiry. They are proud of saying that they only go wherever the evidence leads them. So it might come as a surprise to realize that not only are scientists as biased as non-scientists, but that they are often driven as much by belief as are non-scientists. In fact they are driven by more than belief: they are driven by faith. Science. Belief. Faith. Seeing these words in a sentence alone might make most scientists bristle and want to throw something at the wall or at the writer of this piece. Surely you aren’t painting us with the same brush that you might those who profess religious faith, they might say?

But there’s a method to the madness here. First consider what faith is typically defined as – it is belief in the absence of evidence. Now consider what science is in its purest form. It is a leap into the unknown, an extrapolation of what is into what can be. Breakthroughs in science by definition happen “on the edge” of the known. Now what sits on this edge? Not the kind of hard evidence that is so incontrovertible as to dispel any and all questions. On the edge of the known, the data is always wanting, the evidence always lacking, even if not absent. On the edge of the known you have wisps of signal in a sea of noise, tantalizing hints of what may be, with never enough statistical significance to nail down a theory or idea. At the very least, the transition from “no evidence” to “evidence” lies on a continuum. In the absence of good evidence, what does a scientist do? He or she believes. He or she has faith that things will work out. Some call it a sixth sense. Some call it intuition. But “faith” fits the bill equally.

If this reliance on faith seems like heresy, perhaps it’s reassuring to know that such heresies were committed by many of the greatest scientists of all time. All major discoveries, when they are made, at first rely on small pieces of data that are loosely held. A good example comes from the development of theories of atomic structure. Read more »

isn’t it a miracle that

three atoms have combined

in chemical love to become

the slippery substance of that which

both bears and wrecks ships,

of bays that breed and

shelter life —sustain it,

of that essential stuff of bodies,

of billows of mist that rain

and surge through taps,

of glaciers that have weighed

upon continents for millennia,

until now

?

Jim Culleny

4/13/22

by Ethan Seavey

Every hour of every day I hear the pulsating rush of le Periph and I am reminded that Paris is dead. My dorm is at the very bottom of Paris such that if the city were a ball I’d be the spot that hits the ground. I sit in my windowsill. I watch cars drive on the highway in an unending flow, like blood in veins, fish in streams, but they’re all metal idols of life. Life does not go this fast. Life stops to take a rest.

Every hour of every day I hear the pulsating rush of le Periph and I am reminded that Paris is dead. My dorm is at the very bottom of Paris such that if the city were a ball I’d be the spot that hits the ground. I sit in my windowsill. I watch cars drive on the highway in an unending flow, like blood in veins, fish in streams, but they’re all metal idols of life. Life does not go this fast. Life stops to take a rest.

It seems to me that Paris died forty years ago and is now taxidermic like the fawn I saw guarding an antique shop in the 9th arrondissement. Someone must have prepared the fawn’s body to be preserved, then sewn a tailored military uniform for its cartoonish appearance. Through the window it looks perfectly reanimated and proud to be enlisted in the French infantry. Up close it’s just dusty and reminds me that it has been dead for a long time.

Something stopped in Paris in the 1980s. I think it happened when Parisian food stopped developing. You love French food until you live in Paris and then you decide you can’t have another meal of meat, cheese, butter and bread. A waiter in a French café will serve you a brown omelette, ignore you until you’ve properly begged for the check, and proceed to charge you 14 euros. Paris is proud of its food. They won’t change it any time soon. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Color Burst, Costa Rica 2003.

Sughra Raza. Color Burst, Costa Rica 2003.

Analog photo, digitally edited.

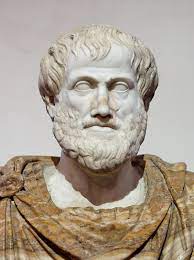

by Dwight Furrow

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life has been revived in recent years.

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life has been revived in recent years.

However, if philosophy is to be successfully conceptualized as a way of life, it will have to overcome that legacy of modern moral philosophy which has little to say about life as lived. You can sift through the works of Hume, Kant, Mill, and their heirs without discovering much that is practically useful. Of all the mainstream views in ethics, one has to return to the ancient philosophers, most notably Aristotle, and their modern interpreters to find discussions of the nature of human flourishing, practical wisdom, and the qualities of character required to achieve it. But alas, it seems to me, even that return to Aristotle is not sufficient to make the argument for philosophy as a way of life. Despite Aristotle’s laudable sensitivity to practical concerns, his work is afflicted with idealizations that limit its value for everyday moral reflection. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Chris Horner

Two Scenarios

First scenario: you attempt to criticise, condemn or otherwise focus on an unjust regime, act of aggression, atrocity, or cruelty. An example: a school has been bombed and children have died. It is a war crime and you name it as such as an evil, criminal thing. Soon after the words leave your mouth, or get posted online, someone responds with something along these lines: yes, that’s all very well, but why just condemn that? What about..? They then name some other, maybe similar atrocity that you haven’t mentioned. The case you wanted to draw attention to is lost, displaced and deferred to other examples that your interlocutor claims you should be equally concerned about. This is what aboutism, and it can be quite annoying.

Second Scenario: someone criticises, condemns or otherwise focuses on an unjust regime, act of aggression, atrocity, cruelty. Let’s say a school has been bombed and children have died. It is a war crime and they name it as such, as an evil, criminal thing. But it is quite obvious to you that they are being selective in their outrage: they don’t seem to care about the times schools have been bombed in other places, by other militaries. Why just this example? So you point this out. All children matter, and not just the ones your interlocutor seems to care about. This is selective outrage, and it can be quite annoying, to put it mildly.

Clearly, one can find oneself on either side of this kind of exchange. One person’s demand for ethical or political consistency can be just a case of what aboutism to another. So is it just the effect of where one is positioned in an argument? Perhaps, but it would be useful to know how to think things through in such a way as to avoid both selective outrage (where only X seems to matter, but not similar cases Y or Z), and mere ‘what aboutism’, which demands an interest in not only case X but in all the other cases that could be considered – an infinite demand that can never be met. Read more »

by David Oates

Full of good cheer – when does walking not perk me up? – on a too-cool March morning, past houses nicer than mine by several hundred grand with wide verandahs and Craftsman gables, and through a deep urban forest of elms, I make my way towards church.

Church!

Not exactly my normal behavior – not for lo these many decades since achieving my apostasy, my ex-Baptist-ness, and then at length making peace with it. I carried no axe to grind. Though I walked right past a low-slung building with a sign reading – no kidding! – “Chinese Baptist Church.”

I’ll return to that. But today my destination is yet more exotic, you could say, though just one more block away. “St. Sharbel Catholic Church, Maronite Rite” it proclaims itself. Whatever that might mean. My mission was to find out by attending the eleven-o’clock service.

This neighborhood, which I live right next to though not quite in – seems oddly attractive to churches. One of the oldest planned developments in the western US, called “Ladd’s Addition” after its 1891 developer, former mayor William S. Ladd, it forms a square just a half-mile on a side, yet is studded with temples and houses of worship, sanctuaries grand or cozy, surprising or predictable . . . so many varieties of religious belief, so many flavors and even hues. Even in ethnically-challenged Portland.

To what end? Serving what need or what god (or gods)? Who can say. Answer: Me. Or I can try, anyway. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Andreu Mas-Collel, a mathematical economist from Catalonia, came to Berkeley before I did. He was a student activist in Barcelona, was expelled from his University for activism (those were the days of Franco’s Spain), and later finished his undergraduate degree in a different university, in north-west Spain. When I met him in Berkeley he was already a high-powered theorist using differential topology in general-equilibrium analysis, in ways that were far beyond my limited technical range in economic theory. But when we met, it was our shared interest in history, politics, and culture that immediately made us good friends, and his warm cheerful personality was an added attraction for me. (His wife, Esther, a mathematician from Chile, was as decent a person as she was politically alert).

Andreu Mas-Collel, a mathematical economist from Catalonia, came to Berkeley before I did. He was a student activist in Barcelona, was expelled from his University for activism (those were the days of Franco’s Spain), and later finished his undergraduate degree in a different university, in north-west Spain. When I met him in Berkeley he was already a high-powered theorist using differential topology in general-equilibrium analysis, in ways that were far beyond my limited technical range in economic theory. But when we met, it was our shared interest in history, politics, and culture that immediately made us good friends, and his warm cheerful personality was an added attraction for me. (His wife, Esther, a mathematician from Chile, was as decent a person as she was politically alert).

A few times it so happened that when I went to see some obscure Latin American film in a special showing at a remote movie hall in Berkeley, at the end when the lights came up, I discovered that Andreu was also in the audience, and then we sat down somewhere to discuss the film animatedly. We used to frequently visit each other’s home. One time Romila Thapar, the eminent historian of ancient India, came to visit us from Delhi, and we asked Andreu and Esther to join us. Later he told others about meeting ‘this very impressive woman’ at our place.

When, after a few years, he left Berkeley, first for Harvard, and then in 1990’s back to Barcelona, I sorely missed him. At Harvard Andreu co-authored what is probably the most used graduate textbook in microeconomic theory in the world. In Barcelona he was a Professor at the Pompeu Fabra University. He later joined politics, serving the Catalonian government in different capacities, including as the Minister of Economy and Knowledge in 2010-16. In 2021 he was slapped with a multi-million-euro penalty by the Spanish Court of Auditors for allegedly participating as Minister in activities that led to the abortive Catalonian bid for independence; I believe the case is still pending. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

After sort-of dissing James Joyce last time around – 0 comments, though! I expected Colm Tóibín to demur or something – this month I was meant to outline what the language of thought is supposed to be like, thus bringing to an end this series on the relationship between language and thought. But before getting to the details of the representational-conceptual system with which we think our thoughts, and in view of the posts I have devoted to claiming that we don’t think in any natural language – that we really don’t think in any language! – I ought to at least discuss the possibility that different languages may well have an effect on the sort of thoughts available to their speakers.

That there might be cross-linguistic differences in cognition is a rather common belief, in fact – who hasn’t been told that this or that word in this or that language is impossible to translate, for instance? – and it has received quite a bit of attention in both academia and the popular science press. Read more »

by Mark Harvey

Out of the blue, between the sea and the sky,

Landward blown on bright, untiring wings;

Out of the South I fly –Maurice Thompson

One of my sisters who is a wildlife biologist often leaves the cinema with an entirely different take on the virtues of any particular movie if it’s set on a natural landscape. Be it an epic love story on the plains of Montana or a character-driven film taking place in the Cascade mountains of the northwest, she and her biologist friends see things through a different lens than you or I. While we might be moved by a love story between a cabin dweller scrapping out an existence while courting a fetching lass from an adjoining homestead, they often leave the same film frustrated and grouchy about how badly and unscientifically the natural world is cast.

“Did you hear that bald eagle?” They’ll say. “That’s not the sound a bald eagle makes! They obviously dubbed the call of a red-tailed hawk over that bald eagle. Who’s going to miss that?”

Well, about 99% of the audience still dabbing their eyes from the happy ending when the homesteaders requite their epic love on the epic landscape.

One thing that seems to really drive my sister and her biologist friends mad is when the director gets the phenology wrong. Phenology, to remind you, is the natural cycle and timing of nature. For example, every spring there is a certain pattern and time frame of flowers blooming, birds returning to the north, insects hatching, and bears coming out of hibernation. So when a film director has the male hero shyly offering flowers to his love interest in one scene and bodice busting in the next, my sister and her crew will cast a clinical eye on the Indian ricegrass and its development between scenes. Read more »

so much depends upon the tale we tell ourselves,

words have the force of love or death,

they can raise or raze. In fact, the typhoon of

a single letter, incessantly said,

can ruin nations

the simplest vertical stroke

“I”

or its Russian solo

“Я”

not to mention the tiny bleating duo

“ME”

in the minds of megalomaniacs, or anyone

who stumbles or steps willfully into a cage of mirrors,

can make a hell of families, countries, churches, schools,

because “me” loves the taste of power

while “we” tastes the power of love

Jim, 4/10/22

(“Я” translation: “I”; Pronunciation: Ya)