by Jochen Szangolies

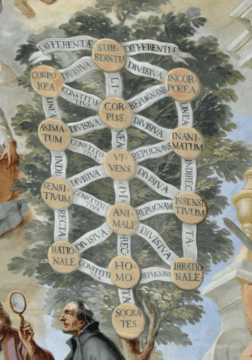

The arbor porphyriana is a scholastic system of classification in which each individual or species is categorized by means of a sequence of differentiations, going from the most general to the specific. Based on the categories of Aristotle, it was introduced by the 3rd century CE logician Porphyry, and a huge influence on the development of medieval scholastic logic. Using its system of differentiae, humans may be classified as ‘substance, corporeal, living, sentient, rational’. Here, the lattermost term is the most specific—the most characteristic of the species. Therefore, rationality—intelligence—is the mark of the human.

However, when we encounter ‘intelligence’ in the news, these days, chances are that it is used not as a quintessentially human quality, but in the context of computation—reporting on the latest spectacle of artificial intelligence, with GPT-3 writing scholarly articles about itself or DALL·E 2 producing close-to-realistic images from verbal descriptions. While this sort of headline has become familiar, lately, a new word has risen in prominence at the top of articles in the relevant publications: the otherwise innocuous modifier ‘general’. Gato, a model developed by DeepMind, we’re told is a ‘generalist’ agent, capable of performing more than 600 distinct tasks. Indeed, according to Nando de Freitas, team lead at DeepMind, ‘the game is over’, with merely the question of scale separating current models from truly general intelligence.

There are several interrelated issues emerging from this trend. A minor one is the devaluation of intelligence as the mark of the human: just as Diogenes’ plucked chicken deflates Plato’s ‘featherless biped’, tomorrow’s AI models might force us to rethink our self-image as ‘rational animals’. But then, arguably, Twitter already accomplishes that.

Slightly more worrying is a cognitive bias in which we take the lower branches of Porphyry’s tree to entail the higher ones. Read more »

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

“

“ In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor.

In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor. Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got.

Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got. Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.

Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn. As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch

As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch  I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.

I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.  I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days.

I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days. Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.