by Paul Braterman

New Zealand is taking measures to reduce the amount of methane and nitrous oxide generated by the flatulence and urinations of its vast flocks of sheep and cattle. No joke; molecule for molecule, methane is about 80 times as effective a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide, while nitrous oxide (laughing gas, an anaesthetic and euphoric) is 300 times as effective.

Such action, according to Ken Ham in Answers in Genesis on 17 October, is not a good idea. As always, the AiG arguments are a hodgepodge of standard denialist pseudoscience, repeatedly rebutted but endlessly recycled, to which I will return at the end of this article, together with a top dressing of biblical references forced into a libertarian straitjacket and mislabelled as religious, leading up to the final conclusion that action on greenhouse gas emissions is misdirected because

“The real problem facing New Zealand and the rest of the world isn’t an emissions problem—it’s our sin problem.”

On a whim, I decided to test this appraisal by collecting just those articles regarding climate change that happened to pop up in my newsfeeds, in the ten days immediately following AiG’s article, and the results are given below. Spoiler: emissions are repeatedly mentioned, but our sin problem is mysteriously absent. Read more »

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous.

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous. Sughra Raza. Valparaiso Expressions. Chile, November 2017.

Sughra Raza. Valparaiso Expressions. Chile, November 2017.

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.

Now there is a

Now there is a

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

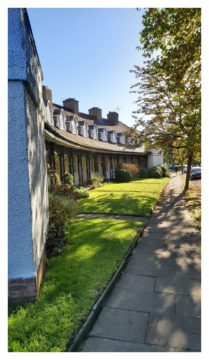

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.