by Christopher Horner

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.

Near the centre of the place is the Lady Lever Art gallery. In there is a large collection of art objects, much of it reflecting the taste, as one might expect, of the times – pre raphaelites art, heavy ‘historical paintings and more. There is also some some art from other periods, including the 18th century. And it’s here I was startled when I visited the place. For one painting depicts a lady of that time, with a black slave. Now there were many people of African origin in England in the late 1700s, perhaps up to three percent of the total population of London (estimates vary a lot). And there are plenty of paintings of the noble and landed gentry and their ladies featuring a black boy or girl as a kind of accessory, perhaps signalling the status of the main subject of the portrait. But this image – of a French mistress and slave, the only one in the gallery to feature a person of colour, was particularly egregious. To quote the Liverpool museums website:

Near the centre of the place is the Lady Lever Art gallery. In there is a large collection of art objects, much of it reflecting the taste, as one might expect, of the times – pre raphaelites art, heavy ‘historical paintings and more. There is also some some art from other periods, including the 18th century. And it’s here I was startled when I visited the place. For one painting depicts a lady of that time, with a black slave. Now there were many people of African origin in England in the late 1700s, perhaps up to three percent of the total population of London (estimates vary a lot). And there are plenty of paintings of the noble and landed gentry and their ladies featuring a black boy or girl as a kind of accessory, perhaps signalling the status of the main subject of the portrait. But this image – of a French mistress and slave, the only one in the gallery to feature a person of colour, was particularly egregious. To quote the Liverpool museums website:

The oil painting, created in 1705 and attributed to Jean Baptiste Santerre (1658-1717), is the Gallery’s only work of art from the 18th century which depicts a person of colour. It shows an enslaved African boy, brought from a plantation to work as an unpaid house servant. His name is not known, and he wears a degrading metal collar around his neck which was used to mark enslaved people as property. Catherine-Marie Legendre (d.1749), was the wife of French nobleman, Claude Pecoil (1629-1722), Marquise de Septème.

At this time, it was not uncommon for wealthy white women to be painted with an enslaved Black servant in a way that signified her position in society. Often dressed in ornate outfits, they were depicted as trappings of wealth. Furthermore, their dark skin was often used in portraiture to highlight the paleness of the sitter’s skin, as pale skin was considered a sign of beauty. Here, the boy is offering a bowl of rare and exotic fruit, while Legendre’s hand rests on the boy’s head to signify her ownership.

On the website, and in the gallery itself, we read these words:

Does this portrait belong on the walls of the gallery today? Does it help us understand and tell the history of slavery or does it continue to honour someone who benefited from the slave trade?

Viewers are then invited to email their comments.

Yes: it does need to be shown. We need more awareness and discussion of the history of slavery, not less, for it still marks our world in many ways, and Liverpool was a major contributor to the slave trade of the 18th century. Fortunately, Liverpool museums seem to have worked with the local Black Lives Matter movement in coming to the design to show it. Alyson Pollard, Head of the Lady Lever Art Gallery writes (and this is on the wall in the gallery, as well):

The Lady Lever Art Gallery is seeking to display, more openly, the Black histories and stories linked to the Transatlantic Slave Trade and its legacies which are not currently transparent in the collections. Displaying this disturbing painting prominently, and acknowledging its context is the beginning of a long-term project to ensure our collections are not seen and viewed through a single historic lens but instead reflect multiple histories. The painting was previously displayed high up on a wall in the William and Mary room and under reflective glass. Its depiction of life for the very wealthy and of the injustices suffered by people of colour at this time make this a very significant image and one which we felt needed to be in a more prominent location.

A short walk from the Lady Lever Art Gallery takes you to the Port Sunlight Museum, where there is more to learn about the economy of empire. Here we learn that the ‘enlightened’ Lever drew on forced labour in the Belgian Congo to supply the palm oil for his soap. And he was an enthusiastic liberal imperialist: the resources for his manufacture lay in the places he wanted to see the empire expanded into. The website adds:

This re-display is one of several actions which the Lady Lever Art Gallery is taking in response to Black Lives Matter and the death of George Floyd. This includes openly acknowledging Lord Lever’s activities in West Africa during the period 1911 to 1925 and beginning the process of reinterpreting its collection.

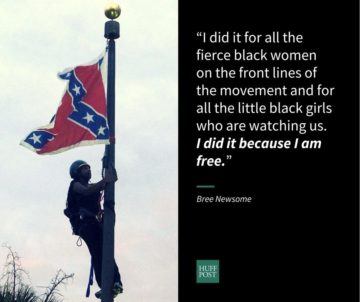

Some people will argue that ‘the past cannot be judged by todays standards’. I disagree. Firstly, ‘todays standards’ where shared by many people in the time of slavery: it was denounced and fought against at the time. That is one of the reasons it doesn’t exist now. It’s also the case that the racism of slavery continues to have its long afterlife. The killing of black men and women by the law enforcement agencies in the USA, UK, France and beyond tell us something about where we are, or aren’t, when it comes to race and justice.

Some people will argue that ‘the past cannot be judged by todays standards’. I disagree. Firstly, ‘todays standards’ where shared by many people in the time of slavery: it was denounced and fought against at the time. That is one of the reasons it doesn’t exist now. It’s also the case that the racism of slavery continues to have its long afterlife. The killing of black men and women by the law enforcement agencies in the USA, UK, France and beyond tell us something about where we are, or aren’t, when it comes to race and justice.

The BLM movement, and others like it, have forced a discussion about that past, and what it means. BLM is not ‘identity politics’: it is a universalistic demand for justice for all: black lives clearly have not, do not, matter to too many of those with the power of life and death. BLM is the latest example of the way in which what we do now helps change the meaning of the past. The aim, that of justice, surely casts a light back on to the numberless others who were used and crushed by chattel slavery – among whom that boy in the picture was one. Let them come from the shadows. Let him be seen.

Walter Benjamin famously wrote that “There is no document of civilisation that is not at the same time a document of barbarism,” and the Santerre painting can surely stand as an example of of that. But there is another insight that occurs to me in this context: that the meaning of the past, including identity of the winners and losers of past struggles, is not settled. What we do now changes the meaning of what went before:

Walter Benjamin famously wrote that “There is no document of civilisation that is not at the same time a document of barbarism,” and the Santerre painting can surely stand as an example of of that. But there is another insight that occurs to me in this context: that the meaning of the past, including identity of the winners and losers of past struggles, is not settled. What we do now changes the meaning of what went before:

Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious. [1]

[1] Benjamin, W: On the Concept of History https://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/books/Concept_History_Benjamin.pdf