by Andrew Bard Schmookler

[This is the sixth and final entry in the series I’ve offered here.]

Please Permit Me to Talk as if Compelled by Truth Serum

It’s an awkward position to be in. Much of what I’ve spent more than a half century creating would likely die with me if I died now. Which would be no big deal except that I have long strongly believed it could prove valuable to a human future I care deeply about.

That has driven me, in my mid-70s, to throw caution to the wind. Which means doing everything in my power to get this creation of mine out into the world far enough that it would survive my own death.

The awkwardness involves my having come to the judgment that this “everything” includes my making claims that some may dismiss as grandiose. But my conviction of the validity of those claims compels me to take that risk.

What I feel impelled to get out into other people’s minds – so it would not die with me – is what I call an “integrative vision” for understanding the human story: a way of seeing things whole that has important implications for how we see ourselves as a species, how we understand what we see in the pages of human history, and how we perceive the challenges humankind must meet if our civilization is to survive for the long haul.

For a while, I tried to resign myself to the reality that, despite my efforts, most of that “integrative vision” would disappear with me. That would have worked, had I been able to look at it just in terms of my life, and my desires. I’ve had my share of wishes come true.

But that’s never been what it’s mostly about. Since the first big piece of that integrative vision came to me in 1970, I have always been driven by the conviction that there was something here that might help humankind survive for the long haul, rather than end our species’ story in self-destruction. Read more »

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough.

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough. Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import.

Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import. Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

Soon after the pandemic commenced its

Soon after the pandemic commenced its  There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published

There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published  This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s.

This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s.

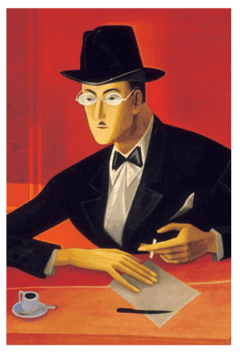

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.