by Dwight Furrow

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

While all these factors contribute to one’s identity, they don’t reach what makes each of us a distinct individual. Why should that matter? It matters in part because we want to be treated as an individual not a type, but also because having an understanding of one’s distinctive identity might help us decide what kind of life to live. It might help us guide our self-formation by reinforcing decisions tailored to one’s very specific needs, values, and aspirations.

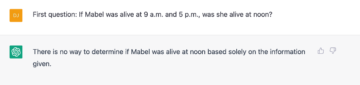

So what does constitute our distinctiveness as persons? We might try to answer this by thinking about cases in which one’s identity is missing—what is commonly called an identity crisis. In an identity crisis we question our purpose in life, what our role or place in society is, what values we ought to be committed to, or the meaning and significance of our activities. But having purpose, meaning, and a commitment to certain values doesn’t quite individuate us either. We share values, commitments, and meanings with many others. These all seem necessary to us as individuals but aren’t sufficient to explain what makes us the distinctive selves we are.

When confronted with such puzzles we might hope that philosophy could straighten us out. However, the results of philosophical inquiry into questions of personal identity are mixed, although I think in the end helpful. Read more »

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

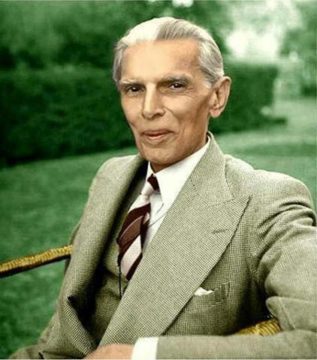

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes.

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes. Ideas often become popular long after their philosophical heyday. This seems to be the case for a cluster of ideas centring on the notion of ‘lived experience’, something I first came across when studying existentialism and phenomenology many years ago. The popular versions of these ideas are seen in expressions such as ‘my truth’ and ‘your truth’, and the tendency to give priority to feelings over dispassionate factual information or even rationality. The BBC is running a radio series entitled ‘I feel therefore I am’ which gives a sense of the influence this movement is having on our culture, and an NHS trust has apparently advertised for a ‘director of lived experience’.

Ideas often become popular long after their philosophical heyday. This seems to be the case for a cluster of ideas centring on the notion of ‘lived experience’, something I first came across when studying existentialism and phenomenology many years ago. The popular versions of these ideas are seen in expressions such as ‘my truth’ and ‘your truth’, and the tendency to give priority to feelings over dispassionate factual information or even rationality. The BBC is running a radio series entitled ‘I feel therefore I am’ which gives a sense of the influence this movement is having on our culture, and an NHS trust has apparently advertised for a ‘director of lived experience’.