by Eric Bies

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

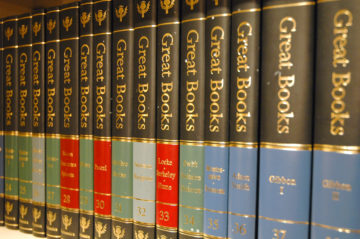

A week later, John Gardner turned 44—a fortuitous number, for the American novelist and medievalist was on a roll. That year alone he was set to see the publication of two children’s books, a collection of short stories, a work of criticism, and a biography. Six years had passed since the release of a short novel, Grendel, his ingenious Frankenstein-ing of the Beowulf myth that is read in American high schools to this day. Eleven years later, at the age of 49, Fate would see fit to fling him from his motorcycle and strike him dead. But first, in 1977, he had to publish his Life and Times of Chaucer. Owing to novelistic tendencies, the work has probably received more admiration from laymen than academics (rather redemptive as far as literary legacies go, actually). It is one of those books, unhampered by its erudition, that is a joy to read all the way through to the bitter end, and its final paragraph, as Steve Donoghue has pointed out, remains one of the strangest, strongest, and most memorable deathbed scenes in our literature:

When he finished he handed the quill to Lewis. He could see the boy’s features clearly now, could see everything clearly, his “whole soul in his eyes”—another line out of some old poem, he thought sadly, and then, ironically, more sadly yet, “Farewell my bok and my devocioun!” Then in panic he realized, but only for an instant, that he was dead, falling violently toward Christ.

The “bok” to which Chaucer says his goodbye is, of course, The Canterbury Tales. Had he had the time, Chaucer would have gladly doubled the length of his book. Who knows what he must have truly felt to take leave of his Knight, his Miller, his Pardoner, his Monk? Readers of this magnificent story cycle will readily sympathize. For even a writer as self-assured as Chaucer could not have anticipated how well and how dearly his countrymen would come to know his characters. The fact that the book remained unfinished at the time of his death did practically nothing to impede its momentous rise. Thankfully, just sixteen years after Chaucer fell violently toward Christ, England got its Gutenberg. When William Caxton set up press in Westminster, the first pages he printed were wet with the ink of Chaucer’s quill. Read more »

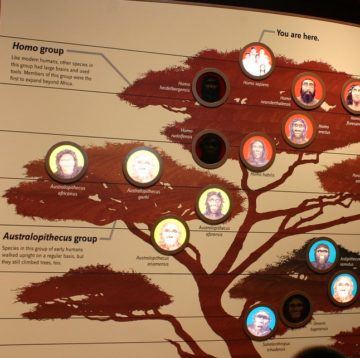

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

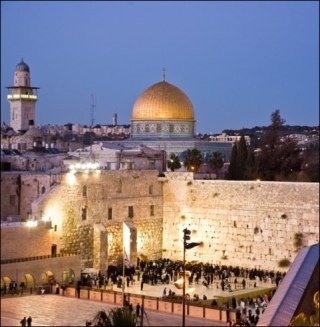

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

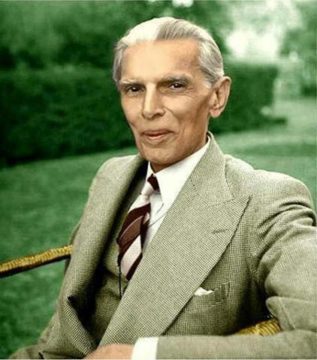

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944