by Tim Sommers

Here’s the gist of it. I think a recent declaration on animal consciousness, being signed by a growing number of philosophers and scientists, is largely correct about nonhuman animals possessing consciousness, but misleading. It insinuates that animal consciousness is a recent discovery – made in the last five to ten years – based on new experimental work. As exciting and revelatory as recent work on the minds of nonhuman animals is, animal consciousness is hardly a new discovery. In fact, I am not sure the declaration is really a scientific manifesto so much as a moral one. We ought to be treating nonhuman animals better because many seem to have some level of consciousness, but implying we should do so because of new “scientific evidence” may be a mistake.

NBC recently reported that “discoveries…in the last five years” show that a “surprising range of creatures” exhibit “evidence of conscious thought or experience, including insects, fish and some crustaceans.”

“That has prompted a group of top researchers on animal cognition to publish a new pronouncement that they hope will transform how scientists and society view — and care — for animals.”

“Nearly 40 researchers signed The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness, which was first presented at a conference at New York University.” Many more have signed the Declaration since then, and many more are likely to sign it in the near future.

Here is The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness in its entirety.

“Which animals have the capacity for conscious experience? While much uncertainty remains, some points of wide agreement have emerged.

First, there is strong scientific support for attributions of conscious experience to other mammals and to birds.

Second, the empirical evidence indicates at least a realistic possibility of conscious experience in all vertebrates (including reptiles, amphibians, and fishes) and many invertebrates (including, at minimum, cephalopod mollusks, decapod crustaceans, and insects).

Third, when there is a realistic possibility of conscious experience in an animal, it is irresponsible to ignore that possibility in decisions affecting that animal. We should consider welfare risks and use the evidence to inform our responses to these risks.”

When I read this my first reaction was “I can’t believe it, they’ve solved the ‘other minds’ problem!” A leading problem in philosophy, after all, has been ‘How do we even know other humans have consciousness?’ – much less nonhuman animals. In fact, one of the signatories to the declaration, leading philosopher of mind David Chalmers, is well-known for arguing that there might be beings (“philosophical zombies”) that look and behave just as we do, but have no consciousness. In other words, recognizing there is a philosophical problem about how we can be justified in attributing consciousness to others. Read more »

Once again the world faces death and destruction, and once again it asks questions. The horrific assaults by Hamas on October 7 last year and the widespread bombing by the Israeli government in Gaza raise old questions of morality, law, history and national identity. We have been here before, and if history is any sad reminder, we will undoubtedly be here again. That is all the more reason to grapple with these questions.

Once again the world faces death and destruction, and once again it asks questions. The horrific assaults by Hamas on October 7 last year and the widespread bombing by the Israeli government in Gaza raise old questions of morality, law, history and national identity. We have been here before, and if history is any sad reminder, we will undoubtedly be here again. That is all the more reason to grapple with these questions.

Sughra Raza. Light Play in The Living Room, November 2023.

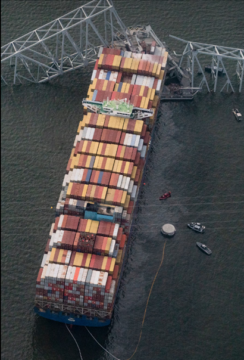

Sughra Raza. Light Play in The Living Room, November 2023. One of nature’s most endearing parlor tricks is the ripple effect. Drop a pebble into a lake and little waves will move out in concentric circles from the point of entry. It’s fun to watch, and lovely too, delivering a tiny aesthetic punch every time we see it. It’s also the well-worn metaphor for a certain kind of cause-and-effect, in which the effect part just keeps going and going. This metaphor is a perfect fit for one of the worst allisions in US maritime history, leading to the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge after it was hit by the container ship MV Dali on the morning of March 26, 2024.

One of nature’s most endearing parlor tricks is the ripple effect. Drop a pebble into a lake and little waves will move out in concentric circles from the point of entry. It’s fun to watch, and lovely too, delivering a tiny aesthetic punch every time we see it. It’s also the well-worn metaphor for a certain kind of cause-and-effect, in which the effect part just keeps going and going. This metaphor is a perfect fit for one of the worst allisions in US maritime history, leading to the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge after it was hit by the container ship MV Dali on the morning of March 26, 2024.

No matter where you go, Aristotle believes, the rich will be few and the poor many. Yet, to be an oligarch means more than to simply be part of the few, it means to govern as rich. Oligarchs claim political power precisely because of their wealth.

No matter where you go, Aristotle believes, the rich will be few and the poor many. Yet, to be an oligarch means more than to simply be part of the few, it means to govern as rich. Oligarchs claim political power precisely because of their wealth.

Editor-in-chief Sarahanne Field describes herself and her team at the Journal of Trial & Error as wanting to highlight the “ugly side of science — the parts of the process that have gone wrong”.

Editor-in-chief Sarahanne Field describes herself and her team at the Journal of Trial & Error as wanting to highlight the “ugly side of science — the parts of the process that have gone wrong”. Richard Pithouse: Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, suddenly opening up the field of political possibility after a long and exhausting stalemate between the progressive forces, which were largely organized in two groups: the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the trade unions, and the apartheid state. What did Mandela’s release mean to you?

Richard Pithouse: Mandela was released from prison on February 11, 1990, suddenly opening up the field of political possibility after a long and exhausting stalemate between the progressive forces, which were largely organized in two groups: the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the trade unions, and the apartheid state. What did Mandela’s release mean to you? In the years following American independence, many questions would be asked, in different spheres, of what it meant to be a citizen, and

In the years following American independence, many questions would be asked, in different spheres, of what it meant to be a citizen, and  Longevity and eternal youth have frequently been sought after down through the ages, and efforts to keep from dying and fight off age have a long and interesting history.

Longevity and eternal youth have frequently been sought after down through the ages, and efforts to keep from dying and fight off age have a long and interesting history.