by Anitra Pavlico

I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.

I recently read Simone Weil for the first time after having come across numerous references to her over the past year. I broke down and bought Waiting for God despite the intimidating and frankly confusing title. I was not disappointed. One of her essays in particular, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies in View of the Love of God,” has opened and focused my thinking on education and learning in general, whether for children or later in life for the rest of us.

Weil writes that “prayer consists of attention. . . . Although today we seem ignorant [of] it, the formation of the faculty of attention is the true goal and unique interest of all studies.” She explains that by developing our capacity for attention, we can enhance our spiritual practice. Leaving that aside for the moment, it is nonetheless worth exploring what she means by attention. I am very interested (along with countless others) in how we in the internet era are maintaining our ability to focus given ever-multiplying distractions. As a mother of a school-age child, I also have a particular interest in how children are developing their ability to focus in this distracting climate.

Weil essentially promotes a meditative or mindful attitude for children facing challenging subject matter in school:

If someone searches with true attention for the solution to a geometric problem, and if after about an hour has advanced no further than from where they started, they nevertheless advance, during each minute of that hour, in another more mysterious dimension. Without sensing it, without knowing it, this effort that appeared sterile and fruitless has deposited more light in the soul.

Weil’s approach is timely because it makes learning less stressful and more enjoyable for students. Even if it does not seem as if the student is mastering the material, in Weil’s view she is coming closer to understanding by virtue of having focused her attention on it. In an age when students are sleep-deprived and unduly anxious about exams, college prep, and living up to parents’ lofty and usually unreasonable expectations, students may be comforted to hear from Weil that “we confuse attention with a kind of muscular effort. [. . .] Fatigue has no relationship to work. Work is useful effort, whether there is fatigue or not.” What is happening today in our schools is not your typical adolescent turmoil–it is a mental health epidemic. Suicide rates have surged; two-thirds of college students report “overwhelming anxiety.” [1] Clearly, merely applying more effort is backfiring. Read more »

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

When it comes to evil, nobody beats Hitler. He committed the biggest mass murder of innocent humans in all of history.

When it comes to evil, nobody beats Hitler. He committed the biggest mass murder of innocent humans in all of history.

Many years ago in 1991, in my first job out of college, I worked for a small investment bank. By 1994, I was working in its IT department. One of my tasks was PC support and I had a modem attached to my computer so that I could connect to Compuserve for research on technical issues. Yes, this was the heydey of Compuserve, the year that the first web browser came out and a time when most people had very little idea, if any, what this Internet thing was.

Many years ago in 1991, in my first job out of college, I worked for a small investment bank. By 1994, I was working in its IT department. One of my tasks was PC support and I had a modem attached to my computer so that I could connect to Compuserve for research on technical issues. Yes, this was the heydey of Compuserve, the year that the first web browser came out and a time when most people had very little idea, if any, what this Internet thing was.

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there. In the fall of 1971, I set out from the small New Hampshire town where I’d spent the first 17 years of my life and rode a Greyhound bus to New Haven. I had a trunk of clothes, a portable stereo housed in a red Samsonite suitcase, and a couple dozen vinyl albums—Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, the Rolling Stones—that I hauled up three flights of stairs to a fourth-floor dormitory room. Yale had gone coed two years before, but ours was the first class in which women would complete the full four years.

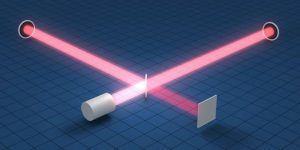

In the fall of 1971, I set out from the small New Hampshire town where I’d spent the first 17 years of my life and rode a Greyhound bus to New Haven. I had a trunk of clothes, a portable stereo housed in a red Samsonite suitcase, and a couple dozen vinyl albums—Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, the Rolling Stones—that I hauled up three flights of stairs to a fourth-floor dormitory room. Yale had gone coed two years before, but ours was the first class in which women would complete the full four years. Light always moves at the same, constant speed: c, or 299,792,458 m/s. That’s the speed of light in a vacuum, and LIGO has vacuum chambers inside both arms. The thing is, when a gravitational wave passes through each arm, lengthening or shortening the arm, it also lengthens or shortens the wavelength of the light within it by a corresponding amount.

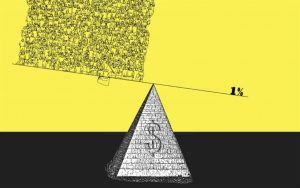

Light always moves at the same, constant speed: c, or 299,792,458 m/s. That’s the speed of light in a vacuum, and LIGO has vacuum chambers inside both arms. The thing is, when a gravitational wave passes through each arm, lengthening or shortening the arm, it also lengthens or shortens the wavelength of the light within it by a corresponding amount. After the crash of 2008, the language of inequality began to trickle into the popular discourse. Then the Occupy movement launched it into the mainstream; the fall of 2011 was the first time in generations that concerns about distributive justice drove crowds into the streets and made front-page news. Scholars, pundits, and politicians all took note, and before long, Gornick and her colleagues found themselves at the center of what President Barack Obama

After the crash of 2008, the language of inequality began to trickle into the popular discourse. Then the Occupy movement launched it into the mainstream; the fall of 2011 was the first time in generations that concerns about distributive justice drove crowds into the streets and made front-page news. Scholars, pundits, and politicians all took note, and before long, Gornick and her colleagues found themselves at the center of what President Barack Obama  In his appearance before the Senate Judiciary Committee last week, Brett Kavanaugh put on a prodigious display of vacuity and mendacity. Kavanaugh is the retrograde jurist picked by Donald Trump to fill the Supreme Court vacancy that arose when the Court’s “swing vote,” Anthony Kennedy, retired. His politics is god awful, but that is hardly news. It was a sure thing that Trump would nominate someone with god-awful politics. Because he knows little and cares less about the judicial system, except when it impinges on his financial shenanigans, and because, as part of his pact with “conservatives” Trump outsourced judicial appointments to the Federalist Society, anyone he would nominate was bound to come with god-awful politics. At least, this particular god-awful jurist is well schooled, well spoken (in the way that lawyers are), and intelligent enough to talk like a lawyer or judge, while dissembling shamelessly and saying nothing of substance. That puts him leagues ahead of Trump. It also puts him head and shoulders above the average Republican. But let’s not praise him too much on that account; much the same could be said of Ted Cruz. Because politically the two of them are so much alike, it is instructive to compare Kavanaugh with that villainous Texas Senator.

In his appearance before the Senate Judiciary Committee last week, Brett Kavanaugh put on a prodigious display of vacuity and mendacity. Kavanaugh is the retrograde jurist picked by Donald Trump to fill the Supreme Court vacancy that arose when the Court’s “swing vote,” Anthony Kennedy, retired. His politics is god awful, but that is hardly news. It was a sure thing that Trump would nominate someone with god-awful politics. Because he knows little and cares less about the judicial system, except when it impinges on his financial shenanigans, and because, as part of his pact with “conservatives” Trump outsourced judicial appointments to the Federalist Society, anyone he would nominate was bound to come with god-awful politics. At least, this particular god-awful jurist is well schooled, well spoken (in the way that lawyers are), and intelligent enough to talk like a lawyer or judge, while dissembling shamelessly and saying nothing of substance. That puts him leagues ahead of Trump. It also puts him head and shoulders above the average Republican. But let’s not praise him too much on that account; much the same could be said of Ted Cruz. Because politically the two of them are so much alike, it is instructive to compare Kavanaugh with that villainous Texas Senator. How can arts respond to conflict, human rights violations and impunity? What role can they play in peace building and reconciliation? These questions are raised by Milo Rau’s Congo Tribunal, a multimedia project, consisting of a film, a book, a website, a 3D installation, an exhibition in The Hague and, most centrally, a performance that took place in Bukavu and Berlin. The project has an ambitious bottomline: “where politics fail, only art can take over.” The failure of politics, in this case, lie in the blatant impunity and perpetuation of the violence that engulfs eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since more than twenty years. Milo Rau is very explicit in his political aims,

How can arts respond to conflict, human rights violations and impunity? What role can they play in peace building and reconciliation? These questions are raised by Milo Rau’s Congo Tribunal, a multimedia project, consisting of a film, a book, a website, a 3D installation, an exhibition in The Hague and, most centrally, a performance that took place in Bukavu and Berlin. The project has an ambitious bottomline: “where politics fail, only art can take over.” The failure of politics, in this case, lie in the blatant impunity and perpetuation of the violence that engulfs eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since more than twenty years. Milo Rau is very explicit in his political aims,