by Dave Maier

A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with that or similar titles, related by their authors with varying degrees of chagrin. We all know the ultimate, or at least proximate, source of this concern: that fount of untruth which is Donald Trump’s Twitter feed (with a side of Brexitmania for those across the pond). Even among his supporters – and this is indeed, I think, the most charitable interpretation of the phenomenon in question – Mr. Trump is, as his aide Ms. Conway has put it, best taken “seriously but not literally.” That is, he is not particularly concerned with whether what he says is true, but instead with its effect on his readers and listeners, friendly or hostile.

A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with that or similar titles, related by their authors with varying degrees of chagrin. We all know the ultimate, or at least proximate, source of this concern: that fount of untruth which is Donald Trump’s Twitter feed (with a side of Brexitmania for those across the pond). Even among his supporters – and this is indeed, I think, the most charitable interpretation of the phenomenon in question – Mr. Trump is, as his aide Ms. Conway has put it, best taken “seriously but not literally.” That is, he is not particularly concerned with whether what he says is true, but instead with its effect on his readers and listeners, friendly or hostile.

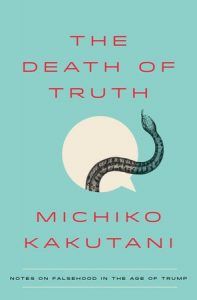

I’m not going to defend this attitude toward truth-telling, which has become known, thanks to philosopher Harry Frankfurt, as “bullshitting,” and in fact dates back to the ancients, when Plato’s Socrates criticized what were called “sophists” for similar attitudes. However, it does seem that some of today’s self-appointed defenders of truth can paint their targets with an excessively broad brush. Naturally there is a lot of complaining about “postmodernist skepticism about truth,” but since most of our writers are not philosophers, their somewhat vague griping is hard to evaluate. (Michiko Kakutani, for example, clearly doesn’t like Derrida; but that’s just about all I got out of what she said.) But I’m not here to defend postmodernism any more than I am to defend “alternative facts.” Read more »

In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”