by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Jeroen Bouterse

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature.

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature.

All of this may be true. As of recently, however, I can’t help but think of him as that guy who spent dozens of pages (more than 80, in a modern printed edition) yelling at a physician.

Or yelling at all physicians, possibly. Petrarch is slightly abstruse about the extent to which he seeks to put down physicians in general, or some subclass of physicians, or this singularly annoying physician in particular.

Petrarch never set much store by physicians. He lived through the horrors of the Black Death, and seems to have concluded from the destruction caused by the Plague that medical professionals were as powerless as anyone against the will of God. When the pope in Avignon fell ill (with a different illness), Petrarch thought it prudent to advise him, in writing, against relying on his doctors. The doctors were none too pleased, and one of them must have written a rebuttal of Petrarch’s letter. It is to this doctor that Petrarch devoted what grew into four books of seething invective. Read more »

Translating a Few Lines by Rehman Rahi

(With a news peg in parenthesis)

Melting snow

a breeze,

(a car explodes,

flesh and bones

litter the road,

the bomber

spliced

to a metal chunk.)

The breeze is a spy.

Here, can’t even

Wailaikum

someone,

and they speak

of dialogue.

To live,

people die.

O Spring

be a witness:

Dumbstruck,

we sing.

—Kashmir, 14 February 2019

Rehman Rahi, b.1925, recipient of several top literary awards in India, is the greatest living poet of the Kashmiri language. He has published five collections of poems and seven books of literary criticism. Rahi lives in Srinagar.

Translated from the original Kashmiri by Rafiq Kathwari / @brownpundit

by Adele A Wilby

History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events.

History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events.

Akkerman’s Invisible Agents is ‘the first full-length study of women’s espionage in seventeenth century Britain…arguably the decades that witnessed a significant increase of female participation in the trade of confidential information.’ Indeed, Akkerman asserts that, ‘female spying activities were at the very heart of British international relations in the mid-seventeenth century’. Her book therefore, has significance for a wider understanding of just how far women were instrumental in shaping the politics of the time. Read more »

by Gabrielle C. Durham

A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

What constitutes cursing? The intention I have in mind is not the imprecations hurled in movies at unsuspecting victims to drag down imminent posterity. No, I mean uttering profanities. Delicious four-letter words that got our knuckles rapped, our mouths washed out with soap, and led to smirking asides through our intentional and unintentional double entendres as teenagers. An excellent overview of dirty words, aka vulgarity, is the classic George Carlin bit on the seven dirty words. Read more »

An ocean of alps visible from airplane window just after takeoff from Innsbruck in December of 2018.

by Christopher Bacas

“I don’t think everyone should have money. It shouldn’t be for everybody—you wouldn’t know who was important. How boring. Who would you gossip about? Who would you put down? Never that great feeling of somebody saying “Can I borrow twenty-five dollars” —Andy Warhol

It starts with the phone. On a nightstand, in the pocket, or ringing under a falling tree in that hypothetical forest. If they offer a gig, unless it’s on a sacred day, you take it. No, is the road less travelled, yes, an adventure. Not often the trailblazing kind. You may work for intrepid souls, but you’ll be chopping wood or carrying quarter notes.

I got a preparatory call. A pianist buddy sounded me about dates, explaining that Billy, a singer, had been off the scene for a while. He sold me on the band, a very strong lineup. The pay was above average, too. Billy called me in a few minutes. We hadn’t met and he never heard me play, but he piled up awkward compliments.

Billy was the son of diplomats, educated in the finest schools and an attorney. Past, present, future, he never once mentioned his own work. The first gigs were an education. We packed a sextet around a piano bar in the city’s fanciest hotel. Attending, high rollers and local television personalities. Joining us, duetting singers and jazz royalty. The duets weren’t rehearsed, a fact Billy aggressively promoted. The other singers were always so highly skilled and poised that his apologies came off as false modesty. The jazz greats were gracious. Billy also introduced any substitute players with the unsmiling caveat “I don’t know him. My pianist recommended him.” Read more »

by Max Sirak

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann)

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann)

All of our contact with the world starts with our feet… (Yoga Ranger Studio, Aprille Walker)

They are our vehicle. They move us in any direction we choose. They are the first impression we make. They are our calling card, hug, and handshake with the world.

They are our feet.

It Was A Day Like Any Other

I needed a new pair of shoes. Need is the appropriate word. Despite my intellectual acceptance of  impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt? I bought it at a concert in high school.)

impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt? I bought it at a concert in high school.)

It’s also fair to note – sartorial excess isn’t a vice I embrace. For example, I own a single pair of jeans. When they begin to fall apart, I’ll get a new pair. This is the general way I approach my wardrobe.

So, as I was trying to tape my left shoe back together, it became apparent the time for patchwork fixes had come and gone. There was no re-attaching my sole.

It was time to discard the old that I might regard new.

My first instinct was to go online. It is, after all, 2019. I have the power to click buttons and make things appear, as if by magic, at my door. However, having been burnt once or twice (three times a lady?), I’m wary when it comes to ordering online the wears I wear. Read more »

by Thomas R. Wells

There are people living among us who have done terrible things to other human beings – murder and rape, for example – yet who nonetheless deserve society’s forgiveness. They have been convicted for their crimes and punished by the laws we collectively agreed such moral transgressions deserve. Now they deserve something other than punishment. They deserve to be treated with respect rather than resentment, contempt, and suspicion. They deserve a real chance to overcome their history and make something of their life.

I

When someone commits a morally terrible act against another that is a concern for the whole society rather than only the victim. Hence the institutions of police, courts and prisons administered by the state on behalf of the people. These systems are designed to discover the moral facts of each case: how bad the crime was, how responsible the perpetrator, and how much they deserve to be punished. This is important to make sure that we punish the people who do terrible things (and only those people), and also that we punish them to the degree that they deserve it and no more.

The last point is essential. We have a duty to punish the people who do bad things, but we have no right to punish them more than they deserve. For the same reason that it is wrongful to punish the wrong person for a crime, it is wrongful to punish the right person in the wrong way. This is why it is important for us to leave the judging to specialist institutions with the resources and authority to do it properly. When we try to do it ourselves we get mob justice – i.e. punishment only stops when those with the most extreme feelings about the case are satisfied.

In most developed countries the criminal justice system is trusted well enough to decide who is guilty and deserves punishment, i.e. who is a criminal. However, it seems that some people hold a lingering belief in their personal right to decide how much punishment criminals deserve to receive, and to inflict that privately if they have the chance. Thus, people with convictions for murder are routinely harassed and denied employment or access to opportunities like university education. Read more »

by Abigail Akavia

As was to be expected, artists are now calling to relocate the next Eurovision Song Contest, which is to be held in Israel in May. No less predictably, supporters are saying, more or less, “let’s leave politics out of it”. As if the Eurovision is nothing but a celebration of music, a friendly competition where sportsmanship is what counts above else. As if, indeed, athletic competitions have nothing to do with politics. The Eurovision has been described as the “Gay Olympics” or the “Gay World Cup.” The analogy brings to mind the controversies surrounding Russia’s hosting of the 2018 world cup games, despite the country’s well-documented violations of human rights. The example of Russia is telling, since there was quite a lot of criticism aimed at FIFA this summer, not for allowing Russia to host per se, but for failing to secure the games as a racism-free zone. In the 2014 Eurovision held in Copenhagen, the Russian representatives were loudly booed in response to Russia’s recent annexation of Crimea and its stance on gay rights. Like it or not, Eurovision participants are held as representatives of their nation, and are judged as such. Thus, even though Eurovision fans display a “playful nationalism” in their celebratory participation in the events, and often support not only their nation’s song but also the one they deem most worthy, the Eurovision remains an overt political arena where two issues are at stake: nationalism and queerness.

A local controversy surrounding one of the runner-ups to become Israel’s contestant to the Eurovision illuminates these two contexts and how they intersect. The next performer to represent Israel on the Eurovision Song Contest will be chosen in a pre-competition reality show called “The Next Star.” Since the competition began two and half months ago, one of the contestants has gained particular attention. Rotem Shefi, a Jewish Israeli singer, performs under the stage-persona of Shefita, an Arab diva, whose props include tacky gowns, heavy jewelry, a glittery walking-cane (yup), and, the most important in her toolbox, a thick Arabic accent. Shefi’s songs in the competition have so far been almost exclusively covers, remakes of rock and pop hits rendered in a non-specific Middle Eastern, pseudo-Arabic sound, performed in English. Despite some signs of unease, especially among one of the show’s judges, Shefita is consistently voted up, and is still presented as a likely contender to win and become Israel’s representative to the Eurovision. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Fire in the Mangrove Swamp. Yucatan, Mexico, October, 2018.

Digital photograph.

by Shawn Crawford

If T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” is the sacred text of Modernist poetry (With Joyce’s Ulysses the sacred novel), then his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” provides the theology to interpret and understand the poem’s byzantine lines and obscure references. How we pored over both, seeking to fathom the mysteries locked inside.

For a Kansas kid raised in a strict Baptist home, the delight of not only reading literature but being surrounded by others with the same desire, cannot be adequately described. “What are you going to do with an English degree?” people would always ask. I knew exactly: I was going To Know, to master the most beautifully written words–the ones that gave me an electric thrill and transcended my shyness and fears—words that provided a solace from the nagging worry about the disposition of my eternal soul. Those words offered salvation of an entirely different kind than the Bible.

Eliot seemed to offer up the perfect life; like many converts to a new religion or culture, he became more British than the British. He had achieved inclusion in the Norton Anthology of English Literature as well as the American Literature anthology. Eliot’s family came from St. Louis, and he was born there. My girlfriend’s family lived in St. Louis. Shocking. Unlike Ezra Pound, who always played with a bumpkin persona he called Uncle Ez, Eliot worked to obliterate all traces of his American identity.

How could he achieve this as an artist, and in his case, as a person? Read more »

by Joan Harvey

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.

I began to think more about the social aspects of illness when today’s usual protocol was not followed. It’s a truism to say we often notice things more in their absence, and it was the lack of shared information when someone I cared for was dying that made me aware how accustomed we are to being included in the progress (or lack thereof) of the cancer patient and how we come to depend on receiving a steady stream of updates on the ill. When this doesn’t happen and we aren’t notified of all the steps toward healing or death along the way, we feel cut off, and this can create a sense of deprivation. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Samia Altaf

“Let’s go look at the flowers outside,” I say, as I sense Dad sinking into the recesses of his fading memory. I wheel him out. Look at the petunias. What a riot—purple, pink, white, that ordinary pedestrian flower in such abundant glory. I hold a bunch to his nose and he takes a deep breath. “Wow,” he says, and opens his eyes. The misty and faraway look hits me hard. It is like looking inside a bombed-out building that has few windows left intact and very little light. But he tries, never having been one to give up; he blinks shortsightedly at the greenery, the flowers, and the blue sky, and shakes his head at the wonder of it all—and of him being there in the middle of it. He struggles to say something but gives up halfway—words too have faded. “Wow,” he says again.

Dad has steadily and imperceptibly lost all memory to Alzheimer’s. Memories of his children, friends, family, his wife now gone. Only shards of crystallized knowledge—encoded so deeply—remain beyond the cognitive deterioration, He recognizes the simple beauty of flowers, they are still real. We look at the yellow rose bush, the petunias and the marigolds, this lovely spring evening. His face lights up. “Wow,” he says, over and over. And then: “I have these in my house” and “when will I go there?” He asks, a complete sentence, and looks anxiously at me, his brow scrunched with a look fit to break your heart. That he remembers—his house and the feeling of wanting to go there. One he had to leave when he and mom got to be too sick to live on their own. Do memories plague his ears, like flies?

“Do memories plague their ears like flies?

They shake their heads. Dusk brims the shadows.

Summer by summer all stole away,

The starting gates, the crowds and cries.”

(Philip Larkin)

“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

“Luddite” is a word that is thrown around a lot these days. It signifies someone who is opposed to technological progress, or who is at least not climbing on board the technological bandwagon. 21st century luddites tend to eschew social media, prefer presentations without PowerPoint, still write cheques, and may even, in extreme cases, get by without a cell phone. When used in the first person, “luddite” is often a badge of honour. “I’m a bit of a luddite,” usually means “I see through and am unimpressed by the false promise of constant technological novelty.” Used in the third person, though, it typically suggests criticism. “So-and-so’s a bit of a luddite,” is likely to imply that So-and-so finds the latest technology confusing and has failed to keep up with it, probably due to intellectual limitations.

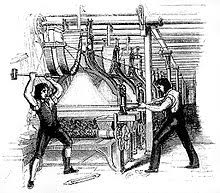

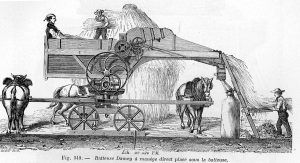

The original Luddites were English textile workers in the Midlands and the North who organized themselves in secret and destroyed machines in the newly established factories and mills. They were called “Luddites” after their fictitious leader, “General Ludd.” Peak Luddism occurred around 1812-1813, although there were incidents of machine breaking before and after then. The most notable of these were the Swing riots that swept across parts of Southern England in 1830 when impoverished agricultural labourers, sometimes carrying out threats issued by the fictitious Captain Swing, smashed threshing machines, burned barns, and demanded higher wages.

A common view today of these machine-breakers in the early stages of the industrial revolution is that they represent a clearly futile attempt to block technological innovation. One can sympathize with their plight, of course. Weavers who were proud of skills they had spent years mastering could now be replaced by relatively unskilled workers operating the new machines. Agricultural labourers who counted on threshing with hand flails for several months of employment following the harvest now faced winters without work or wages. But the times they were a-changing. Quite simply, the new methods of production could produce much more in less time and at lower cost. Trying to halt progress of this sort is as pointless as ordering back the tide. Resistance is futile.

But this view of the people who smashed stocking looms and threshing machines is oversimplified and somewhat unjust. It also carries some questionable ideological freight. Let me explain. Read more »

Savannah grasslands in Murchison Falls National Park in Uganda at sunrise one morning in December of 2018.

by Liam Heneghan

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow.

The traffic had been slow all day but by four pm, it was reduced to a trickle. Those cars that passed him on the street did so in two and threes as if they were sticking together for safety like lumbering animals caught out in a storm. It was, in fact, a very harsh winter day. The afternoon temperatures dipped well below zero: one of the coldest days ever recorded in Chicago. The only sounds now were from an occasional plane passing overhead, and from distant cackling from those venturesome neighbors who had left snug homes to experience the cold. He could hear the sound of his feet crunching through the snow.

The husband and wife had left the house to drop off a bag of groceries to a nearby homeless shelter. Peanut butter, cans of peaches, mandarin oranges in a light syrup, crackers, nuts, and so on: things that people accumulate in abundance for emergencies that rarely materialize. He stepped out of the car to drop off the goods, and walked down the short flight of stairs into a reception area in the basement of the church. The volunteer welcomed him with gusto; she had said “Welcome”, rather grandly, and looked at him expectantly. She seemed confused when he extended his shopping bag. “Donations,” he said. “Ah…!” she replied as she realized that he would not be staying. Another volunteer elaborately produced a receipt and he was required to jot down the list of items he was leaving behind. He found that he could not remember all the items, and made a few of them up.

As he left the shelter, he suppressed a smile and once back in the car he and his wife laughed at the confusion as she drove them away. It seemed like the sort of thing that always happened to him. The sort of thing that would also happen to his father, he reflected. After a few minutes, they fell silent, both ruminating, no doubt, on those now suffering without shelter. The husband abruptly declared he wanted to walk home and got out of the car. “I am looking more and more like my father,” thought the husband. The wife drove on. Read more »

by Joseph Shieber

One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism.

One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism.

Roughly, according to verificationism, a claim has meaning just in case it is possible to verify the claim — either through empirical evidence or logical proof.

Now here’s the problem for a claim that expresses belief in God. There is no empirical evidence that can prove the existence of God, nor is it possible, purely through logic alone, to prove God’s existence. So, according to verificationism, a claim like “God exists” is quite literally meaningless. It’s just nonsense. Though grammatical, it’s no more meaningful than “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously”.

What made me think of verificationism and theism recently is the fact that, in the last couple of weeks (and, indeed, years), a number of religious people have claimed that God had a particular interest in the outcome of the 2016 United States Presidential election.

Now it seems to me that we can show that such claims are pretty obviously nonsensical. And it seems to me that we can do this without accepting anything as strong as the verificationist thesis. In fact, we can do this even according to the standards of a committed religious believer. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As I noted last month, agency in the wine community is dispersed with many independent actors having some influence on wine quality. This dispersed community is held together by conventions and traditions that foster the reproduction of wine styles and maintain quality standards. Most major wine styles are embedded in traditions that go back hundreds of years and are still vibrant today. Although the genetic instability of grapes and their sensitivity to minor changes in weather, soil and topography are agents of change, most of these changes are minor variations within a context of stability. We create new varietals, discover new wine regions, and develop new technologies and methods but these produce minor deviations from a core concept that sometimes seems immune to radical change. There are, after all, only so many ways to ferment grape juice. Red and white still wine, sparkling wine, and fortified wine have been around for centuries and are still the main wine styles on offer. Every wine we drink is a modification of those major themes.

The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As I noted last month, agency in the wine community is dispersed with many independent actors having some influence on wine quality. This dispersed community is held together by conventions and traditions that foster the reproduction of wine styles and maintain quality standards. Most major wine styles are embedded in traditions that go back hundreds of years and are still vibrant today. Although the genetic instability of grapes and their sensitivity to minor changes in weather, soil and topography are agents of change, most of these changes are minor variations within a context of stability. We create new varietals, discover new wine regions, and develop new technologies and methods but these produce minor deviations from a core concept that sometimes seems immune to radical change. There are, after all, only so many ways to ferment grape juice. Red and white still wine, sparkling wine, and fortified wine have been around for centuries and are still the main wine styles on offer. Every wine we drink is a modification of those major themes.

Nevertheless, sometimes wine styles change, often massively. In a community so bound by tradition how does that change take place? One example of a massive change in taste took place in the U.S. in the decades following WWII, where in the course of about twenty years American wine consumers changed their preference from sweet wine to dry. How did such a revolution in taste occur in such a relatively short period of time? Read more »