by Dave Maier

In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative.

In the Third Essay of On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche levels a powerful attack on the modern Platonistic conception of mind and nature, urging us to reject such “contradictory concepts” as “knowledge in itself,” or the idea of “an eye turned in no particular direction, in which the active and interpreting forces, through which alone seeing becomes seeing something, are supposed to be lacking.” More recently, Donald Davidson’s attack on the dualism of conceptual scheme and empirical content, and thus of belief and meaning, requires us to see inquiry into how things are as essentially interpretative.

This idea can seem to conflict with our natural conception of the world as objective, fundamentally independent of what we say or think. In a similar context, Wittgenstein has his imaginary interlocutor challenge him (Philosophical Investigations §241): “So you are saying that human agreement decides what is true or false?” The implication is clear: if your position requires that what we say makes things true, rather than simply mirrors it, then that is an unacceptably irrealist result; how the world is cannot depend on what we say about it.

The suspicion can also arise – especially when the relevant reflections about language come from those steeped in literary theory – that “interpretivists” have mistakenly extrapolated from what may very well be true in the specific case of artistic interpretation and its objects to any discourse about the world at all. Similarly, defenders of the traditional view of objectivity such as John Searle (following John Austin here) have suggested that it is the specific cases of “illocutionary acts” such as “I hereby pronounce you man and wife,” which do indeed cause their objects to be thus truly described, that have unwittingly led to the interpretivist heresy. Read more »

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text?  “[T]here is in fact nothing that can alleviate that fatal flaw in Darwinism” says Professor Behe,

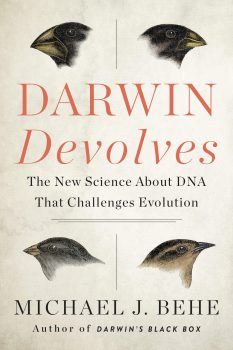

“[T]here is in fact nothing that can alleviate that fatal flaw in Darwinism” says Professor Behe,  rapture, claiming that “Michael Behe’s Darwin Devolves Topples Foundational Claim of Evolutionary Theory” and that “Anyone interested in knowing the truth about the design/evolution debate will find Darwin Devolves a must read.”

rapture, claiming that “Michael Behe’s Darwin Devolves Topples Foundational Claim of Evolutionary Theory” and that “Anyone interested in knowing the truth about the design/evolution debate will find Darwin Devolves a must read.” I wonder whether Behe’s most vociferous supporters actually understand his position. Unlike them, he

I wonder whether Behe’s most vociferous supporters actually understand his position. Unlike them, he

I was lugging several superheavy boxes of dishes up the concrete stairs from the sidewalk to the front door when a guy in a silver suit materialized in front of me. The first rule of moving is that when you pick something up, you don’t put it down until you have it where it goes. This is because picking it up and putting it down are half the battle. So, I tried to go around him.

I was lugging several superheavy boxes of dishes up the concrete stairs from the sidewalk to the front door when a guy in a silver suit materialized in front of me. The first rule of moving is that when you pick something up, you don’t put it down until you have it where it goes. This is because picking it up and putting it down are half the battle. So, I tried to go around him.

The Alps are much grander this morning. I like to think they tiptoed closer in the night, but it’s only an optical illusion created by a local high-pressure system called föhn, which magnifies them and everything else on the horizon. Sitting outside in the loggia, a spacious recessed balcony that resembles a box at the opera, I am audience to many forms of entertainment—weather theater, rainbow theater, sunrise theater, moonrise theater, but best of all, avian theater with its motley cast of bird species performing their life cycles like variations on a theme, in full view.

The Alps are much grander this morning. I like to think they tiptoed closer in the night, but it’s only an optical illusion created by a local high-pressure system called föhn, which magnifies them and everything else on the horizon. Sitting outside in the loggia, a spacious recessed balcony that resembles a box at the opera, I am audience to many forms of entertainment—weather theater, rainbow theater, sunrise theater, moonrise theater, but best of all, avian theater with its motley cast of bird species performing their life cycles like variations on a theme, in full view. When one makes an artwork, something flows from artist to audience. The thing flowing is actually several: concepts, ideas, aesthetic experiences, duration itself, beliefs, attitudes, and probably much more. Artworks work in a similar way to language, although it would be foolish to believe that artworks are language. Their similarities to language end at the transmission from one to another of the things flowing. That’s how language works as well. But for art, as with something like emotion, the flow is vague in how it is sent and received. It seems to me that the best linguistic analogy for what artworks do is located in assertion. Artworks assert a position. Of course it is entirely possible, and even the norm, that their version of assertion is cryptic to the point of being sometimes unintelligible. But assertions don’t need to be crystal clear. One can assert their dominance over another through a series of non-linguistic subtle bodily movements. Likewise, artworks can make assertions through their physical presence.

When one makes an artwork, something flows from artist to audience. The thing flowing is actually several: concepts, ideas, aesthetic experiences, duration itself, beliefs, attitudes, and probably much more. Artworks work in a similar way to language, although it would be foolish to believe that artworks are language. Their similarities to language end at the transmission from one to another of the things flowing. That’s how language works as well. But for art, as with something like emotion, the flow is vague in how it is sent and received. It seems to me that the best linguistic analogy for what artworks do is located in assertion. Artworks assert a position. Of course it is entirely possible, and even the norm, that their version of assertion is cryptic to the point of being sometimes unintelligible. But assertions don’t need to be crystal clear. One can assert their dominance over another through a series of non-linguistic subtle bodily movements. Likewise, artworks can make assertions through their physical presence. Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

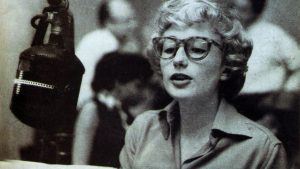

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.