by Brooks Riley

For most of us, the act of looking at a painting is, and should be, subjective. The baggage we bring to the confrontation–how we see, what we notice, what we know, how we feel, what we like or don’t like—is as individual as a finger print, and often highly idiosyncratic. Like the proverbial horse, we can be led to a painting, but we cannot be made to like it—if we’re honest. We may well like it, or appreciate it (divorcing ‘like’ from ‘value’), even if we’ve been led to it. But we can also be cajoled, or conned, into liking it or appreciating it because we’ve been told it’s a masterpiece.

For most of us, the act of looking at a painting is, and should be, subjective. The baggage we bring to the confrontation–how we see, what we notice, what we know, how we feel, what we like or don’t like—is as individual as a finger print, and often highly idiosyncratic. Like the proverbial horse, we can be led to a painting, but we cannot be made to like it—if we’re honest. We may well like it, or appreciate it (divorcing ‘like’ from ‘value’), even if we’ve been led to it. But we can also be cajoled, or conned, into liking it or appreciating it because we’ve been told it’s a masterpiece.

Sometimes I feel I’m being stalked by Leonardo da Vinci. He tiptoes in and out of my life at irregular intervals, calling attention to himself and exhorting me to believe in his painterly genius. It’s aesthetic harassment, and he’s had plenty of enablers over the centuries, telling me I should give in to him.

The first time I saw the Mona Lisa, at 14, the first thing I noticed were her eyebrows, or rather the lack of them. Like a homing pigeon, my attention swiftly bypassed the painting as gestalt and zoomed directly into a detail that delivered a personal shock of recognition. I didn’t see the smile, I didn’t try to read her expression, I didn’t try to see where she was looking, I didn’t notice the landscape outside the window behind her. I was fixated on that delicate bone along which her eyebrows might have stretched like a delicate punctuation mark on an expression.

In spite of my dark brown hair, I was born with almost no eyebrows, only a few beige weeds scattered helter-skelter in a landscape of pale skin, invisible even from a short distance. At 14, when all my friends had lovely, well-defined brows, my lack of them was a source of adolescent insecurity that eventually faded when the teasing stopped.

By the time I saw the Mona Lisa for the second time, at 22, I’d found out that Lisa shaved off her eyebrows according to Renaissance fashion–I was born too late. This may be what led bandleader Mitch Miller to tell me, when we met, that I looked like a few Madonnas he’d seen at the Frick. It had to be the eyebrows, or the lack of them.

Da Vinci showed up again while I was living in the tiny principality of Liechtenstein for a few months, just as its prince was selling the family’s only da Vinci painting, the Ginevra de’ Benci, to the National Gallery in Washington for a tidy sum that seems like peanuts today. Seeing it on the front page of the International Herald Tribune, I found it refreshingly different from the Mona Lisa, Ginevra’s hard sullen stare somehow more intriguing and mysterious than Mona Lisa’s placid smile over our right shoulder. At the time I was surprised that such a national treasure could be sold away without local protest. When I posed the question, the news dealer in Vaduz shrugged. ‘The prince can do what he wants.’ As I’ve since learned, the prince needed the money.

Back in Washington, I made the pilgrimage to see the Ginevra de’ Benci. There was something exquisitely delicate and old-fashioned about it, like a painting from an earlier century of someone portrayed as an icon of herself. And I sent a postcard of it to my brilliant, neurotic, decades-older half-sister Jane, a successful songwriter who happened to be obsessed with Leonardo da Vinci. Convinced that a certain painting attributed to someone else was, in fact, a true da Vinci, she plunged into research, hand-wrote an 800-page manuscript and left Texas for the first time in her life to take it to a NY publisher. Told that her theory would need to be vetted by experts, Jane, already in the throes of serious paranoia, took the manuscript back to Texas and burned it. There’s more to this story, but it’s safe to say that da Vinci ruined her life.

He wasn’t done with me, either. A few years ago, approached to translate a German novel in which Mona Lisa comes alive to haunt and taunt a contemporary painter—Woody Allen’s The Kugelmass Episode without the humor—I was less than enthusiastic, horrified at the thought of spending serious time with a painting I grudgingly admired whose protagonist I found woefully uninteresting.

Now he’s back, with another questionable work, the Salvator Mundi, which just sold last month for $450 million. To try to understand what it is that bothers me about da Vinci, I’ve spent the intervening weeks immersing myself in his paintings (I just can’t seem to shake this guy.). My conclusions might seem superficial, especially to art historians, but it would take another lifetime to properly prove them. I’d rather spend the rest of this life with Albrecht Dürer.

In spite of his genius, Leonardo lacked a personal aesthetic sense, or an own style. Not a metteur en scène, he was a bricoleur en scène, tinkering around with elements of a painting without paying much mind to its aesthetic whole. Given his prodigious talent, he could have been a great artist. But as a polymath without equal, his interest in painting was scientific, analytical, experimental, but not necessarily artistic. It’s not an accident that he put his ability to paint at the bottom of his qualifications when he applied for a post with the Duke of Milan. He had other things on his mind. As Jean-Pierre Cuzin, a former curator at the Louvre aptly put it, ‘For him the painting doesn’t count. What counts is the knowledge.’

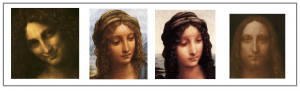

By the time he became obsessed with sfumato—a technique that renders paintings more realistic by ‘smoking’ away the lines of demarcation, creating the illusion of reality through a suggestion of 3-dimensionality—his descent from greatness was precipitate. Sfumato à la Leonardo is a two-dimensional form of embalming that turns everyone into generic figures, like Madonna Barbie dolls against backdrops that often look like back projections. Through his application of sfumato, the faces lose character, becoming waxy figures in a Renaissance Madame Tussaud’s gallery, or in the case of the Salvator Mundi, the Shroud of Turin. The ragazzo pazzo posing as John the Baptist in his last painting also belongs to this sfumato festival.

By the time he became obsessed with sfumato—a technique that renders paintings more realistic by ‘smoking’ away the lines of demarcation, creating the illusion of reality through a suggestion of 3-dimensionality—his descent from greatness was precipitate. Sfumato à la Leonardo is a two-dimensional form of embalming that turns everyone into generic figures, like Madonna Barbie dolls against backdrops that often look like back projections. Through his application of sfumato, the faces lose character, becoming waxy figures in a Renaissance Madame Tussaud’s gallery, or in the case of the Salvator Mundi, the Shroud of Turin. The ragazzo pazzo posing as John the Baptist in his last painting also belongs to this sfumato festival.

It’s no wonder that authentication of da Vinci’s works is so difficult. No two paintings are related in any discernable way unless he painted them twice, which he seems to have done more than once. He’s a painter without a style—essentially a jack-of-all-styles.

It all started well enough. Early works like The Annunciation (in collaboration with Verrocchio) with its cinemascopic one-point perspective seem to suggest a desire to find a style or at least a completed unified image. Early on he also painted my favorite, the Lady with an Ermine, a painting I love in spite of that right hand on steroids (An L.A.M. scan of the painting reveals an earlier hand that’s smaller and a scrawny grey weasel instead of the ermine.). Here I recognize a potential for mise-en-scene in the dynamic polyhedron-esque variation on portraiture with a protagonist whose alert curiosity, aimed off-stage left, immediately invites us to wonder, ‘What is she looking at?” If there’s a masterpiece lurking in da Vinci’s oeuvre, it’s this one. That gaze, clear and unsullied by sfumato, could almost stand as a metaphor for the painter’s own constant distractions, off-stage from painting.

It all started well enough. Early works like The Annunciation (in collaboration with Verrocchio) with its cinemascopic one-point perspective seem to suggest a desire to find a style or at least a completed unified image. Early on he also painted my favorite, the Lady with an Ermine, a painting I love in spite of that right hand on steroids (An L.A.M. scan of the painting reveals an earlier hand that’s smaller and a scrawny grey weasel instead of the ermine.). Here I recognize a potential for mise-en-scene in the dynamic polyhedron-esque variation on portraiture with a protagonist whose alert curiosity, aimed off-stage left, immediately invites us to wonder, ‘What is she looking at?” If there’s a masterpiece lurking in da Vinci’s oeuvre, it’s this one. That gaze, clear and unsullied by sfumato, could almost stand as a metaphor for the painter’s own constant distractions, off-stage from painting.

Leonardo da Vinci was not a consummate painter. He was first and foremost a scientist, inventor and experimenter, with an excess of artistic talent to help pay the rent and a trove of notebooks to document his true obsessions. What I admire and envy about him is that thirst and drive to know everything, and his inventive imagination. I’d prefer to curl up with his codices, which is how I’d probably feel most at ease with him.

Leonardo’s talent allowed him to delve into the mechanics of life and body, the techniques of a craft, including painting, and bold imagined mechanisms of the future. It’s not difficult to detect a case of ADD to a rarified degree. Endowed with extraordinary capabilities, polymaths get easily distracted. They experiment feverishly on one or three things before rushing off to some other new challenge. Da Vinci once said that no painting is ever finished, only abandoned. I rest my case.

Disclaimer: My opinion is defiantly subjective, probably not at all original, and all too brief, but is informed by considerable time and energy spent looking at the forest as well as the trees.