by Joseph Shieber

One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism.

One of the biggest early 20th century philosophical challenges to the belief in God stemmed from the doctrine of verificationism.

Roughly, according to verificationism, a claim has meaning just in case it is possible to verify the claim — either through empirical evidence or logical proof.

Now here’s the problem for a claim that expresses belief in God. There is no empirical evidence that can prove the existence of God, nor is it possible, purely through logic alone, to prove God’s existence. So, according to verificationism, a claim like “God exists” is quite literally meaningless. It’s just nonsense. Though grammatical, it’s no more meaningful than “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously”.

What made me think of verificationism and theism recently is the fact that, in the last couple of weeks (and, indeed, years), a number of religious people have claimed that God had a particular interest in the outcome of the 2016 United States Presidential election.

Now it seems to me that we can show that such claims are pretty obviously nonsensical. And it seems to me that we can do this without accepting anything as strong as the verificationist thesis. In fact, we can do this even according to the standards of a committed religious believer. Read more »

The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As

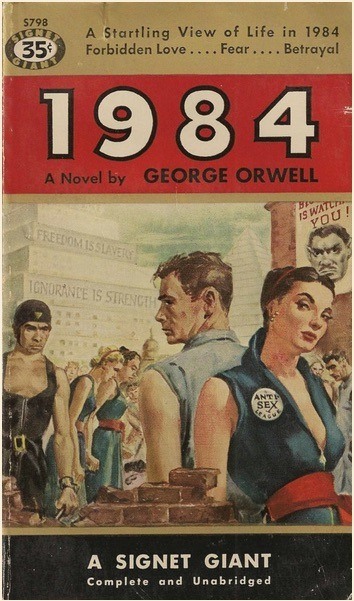

The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As  A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with

A contemporary truism, ironically enough, is that we now live in a “post-truth” era, as attested by a number of recent books with  In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

In October of 1859, Abraham Lincoln received an invitation to come to New York to deliver a lecture at the Abolitionist minster Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

47-year old Teburoro Tito stood at the head of his delegation on an island way out in the Pacific Ocean. At the stroke of midnight on January 1

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”