by Niall Chithelen

1) I got to see a different side of the Forbidden City when I brought visitors to there on a Monday and learned that the Forbidden City is not open to the public on Mondays. The side of the city that I saw was the outside, because Plan B (improvised) was to walk around the Forbidden City to the park behind it, which amounts largely to walking alongside a large, wide gray wall. Truly remarkable, you know, the immaculate geomancy, the imperial wonders and golden roofs. And then the wall and then us on the other side, strolling around as though I did not just commit a grave and truly ignominious error—strolling in pained, weak silence.

2) On any informal tour I lead, I like to show people the real China, you know, not just the tourist spots. Some people might like to see the inside of the Forbidden City, but for most of its existence, common people could not see the Forbidden City, and so it is more appropriate, I think, to walk around it, as a person would have two or three hundred years ago in order to do whatever business or activity people did at that time in this city—perhaps involving carts, or administration, or workplace conflict resolution. I am not sure about this. This is a more legitimate experience—no ticket required—just a channel into Beijing, feet on the ground in this old city, eyes on those old buildings that have seen so many years of change, an injection of pure Beijing right into your goddamn veins, really. And I try to be informative and even-handed as I dole out history and explain contemporary developments. Is China perfect? No. Is the US perfect? Also no. It is so difficult to judge these things. Read more »

No one knows if it was really in the state prison, the ruins of which are visible today outside the ancient Agora of Athens, that Socrates was kept during the final days before his execution, so many times has the area been destroyed and reconstructed— walking past it sends a chill down my spine. Ancient Greece is visceral and vivid because it entered my imagination early in life; some of the most cherished tales of my childhood came from the crossovers of Hellenistic history and legend, such as the one in which Sikander (Alexander the Great) is accompanied by the Quranic Saint Khizr, in pursuit of “aab e hayat,” the elixir of immortality, or the one about the elephantry in the battle between Sikander and the Indian king Porus, or of the loss of Sikander’s beloved horse Bucephalus on a riverbank not far from Lahore, the city where I was born. I became familiar with ancient Greece through classical Urdu poetry and lore as well as through my study of English literature in Pakistan, but I would read Greek philosophers in depth many years later, as a student at Reed college; I would subsequently discover Greek influence on scholars in the golden age of Muslim civilization while working on a book on al-Andalus— the overlooked, key contribution of Arabic which served as a link between Greek and Latin, and its later offshoots that came to define the cultural and intellectual history of Europe.

No one knows if it was really in the state prison, the ruins of which are visible today outside the ancient Agora of Athens, that Socrates was kept during the final days before his execution, so many times has the area been destroyed and reconstructed— walking past it sends a chill down my spine. Ancient Greece is visceral and vivid because it entered my imagination early in life; some of the most cherished tales of my childhood came from the crossovers of Hellenistic history and legend, such as the one in which Sikander (Alexander the Great) is accompanied by the Quranic Saint Khizr, in pursuit of “aab e hayat,” the elixir of immortality, or the one about the elephantry in the battle between Sikander and the Indian king Porus, or of the loss of Sikander’s beloved horse Bucephalus on a riverbank not far from Lahore, the city where I was born. I became familiar with ancient Greece through classical Urdu poetry and lore as well as through my study of English literature in Pakistan, but I would read Greek philosophers in depth many years later, as a student at Reed college; I would subsequently discover Greek influence on scholars in the golden age of Muslim civilization while working on a book on al-Andalus— the overlooked, key contribution of Arabic which served as a link between Greek and Latin, and its later offshoots that came to define the cultural and intellectual history of Europe.

1. “…And I, who timidly hate life, fascinatedly fear death.” Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet.

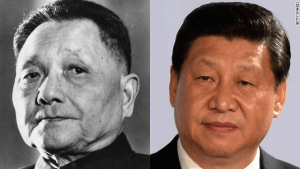

1. “…And I, who timidly hate life, fascinatedly fear death.” Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet. This is the 40th anniversary of the onset of economic ‘reform and opening-up’ (gaige kaifang) in China under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, which eventually led to a dramatic transformation of its economy and global status. It is, however, remarkable that China’s current supreme leader, Xi Jinping, marked the anniversary in a speech in the Great Hall of People in Beijing mainly emphasizing the Party’s pervasive control. It is also remarkable that in recent years this leadership seems to have forsaken Deng’s earlier advice of tao guang yang hui (“keep a low profile”). In the flush of Chinese nationalist glory, Xi explicitly stated in the 19th Party Congress that China has now entered a “new era”, when its model “offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”. Many people both in rich and poor countries seem to be already awe-struck by this model.

This is the 40th anniversary of the onset of economic ‘reform and opening-up’ (gaige kaifang) in China under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, which eventually led to a dramatic transformation of its economy and global status. It is, however, remarkable that China’s current supreme leader, Xi Jinping, marked the anniversary in a speech in the Great Hall of People in Beijing mainly emphasizing the Party’s pervasive control. It is also remarkable that in recent years this leadership seems to have forsaken Deng’s earlier advice of tao guang yang hui (“keep a low profile”). In the flush of Chinese nationalist glory, Xi explicitly stated in the 19th Party Congress that China has now entered a “new era”, when its model “offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”. Many people both in rich and poor countries seem to be already awe-struck by this model.

I wrote the first draft of this post on my typewriter. Like much of my other writing, this piece began as handwritten notes and drafts typed on a nice little portable typewriter, which is a little younger than I am and which I expect to use for the rest of my life.

I wrote the first draft of this post on my typewriter. Like much of my other writing, this piece began as handwritten notes and drafts typed on a nice little portable typewriter, which is a little younger than I am and which I expect to use for the rest of my life.

The traveler comes to a divide. In front of him lies a forest. Behind him lies a deep ravine. He is sure about what he has seen but he isn’t sure what lies ahead. The mostly barren shreds of expectations or the glorious trappings of lands unknown, both are up for grabs in the great casino of life.

The traveler comes to a divide. In front of him lies a forest. Behind him lies a deep ravine. He is sure about what he has seen but he isn’t sure what lies ahead. The mostly barren shreds of expectations or the glorious trappings of lands unknown, both are up for grabs in the great casino of life. Although we know bias and racism exists in most societies, when put into coherent terms in the form of research the impact is stark and exposes just how much a part of life racism is for so many people. Booth and Mohdin’s (The Guardian 2018) article ‘Revealed: the stark evidence of everyday bias in Britain’ setting out the findings of a poll on the levels of negative experience, more often associated with racism, by Black, Asian and minority and ethnic groups in the United Kingdom(UK) does just that. Thus, for example, from amongst its many findings the survey revealed that 43% of those from a minority background had been overlooked for work promotion in the last five years in comparison with only 18% of white people who reported the same experience. Likewise, 38% of people from ethnic minorities said they had been wrongly suspected of shop lifting in the last five years, in comparison with 14% of white people. Significantly, 53% of people from a minority background believed they had been treated differently because of their hair, clothes and appearance, in comparison with 29% of white people. In the work-place also 57% of minorities said they felt they had to work harder to succeed in Britain because of their ethnicity, and 40% said they earned less.

Although we know bias and racism exists in most societies, when put into coherent terms in the form of research the impact is stark and exposes just how much a part of life racism is for so many people. Booth and Mohdin’s (The Guardian 2018) article ‘Revealed: the stark evidence of everyday bias in Britain’ setting out the findings of a poll on the levels of negative experience, more often associated with racism, by Black, Asian and minority and ethnic groups in the United Kingdom(UK) does just that. Thus, for example, from amongst its many findings the survey revealed that 43% of those from a minority background had been overlooked for work promotion in the last five years in comparison with only 18% of white people who reported the same experience. Likewise, 38% of people from ethnic minorities said they had been wrongly suspected of shop lifting in the last five years, in comparison with 14% of white people. Significantly, 53% of people from a minority background believed they had been treated differently because of their hair, clothes and appearance, in comparison with 29% of white people. In the work-place also 57% of minorities said they felt they had to work harder to succeed in Britain because of their ethnicity, and 40% said they earned less. In the immortal words of Prince Rogers Nelson’s party gem from 1982:

In the immortal words of Prince Rogers Nelson’s party gem from 1982:

first day. To the ancients, the sun was God Himself–the Egyptians had Ra, and the Aztecs,

first day. To the ancients, the sun was God Himself–the Egyptians had Ra, and the Aztecs,  monuments to track it. In the dark days of winter we brighten our homes with candles and holiday lights. Winter religious holidays like Christmas and Chanukah emphasize lights and candles to brighten the darkness, while other holidays come during spring, when the days get longer. Many of us feel the need to travel south in

monuments to track it. In the dark days of winter we brighten our homes with candles and holiday lights. Winter religious holidays like Christmas and Chanukah emphasize lights and candles to brighten the darkness, while other holidays come during spring, when the days get longer. Many of us feel the need to travel south in  the dead of winter, to get a few days of bright light and longer days.

the dead of winter, to get a few days of bright light and longer days. “Eets beeg place. Millennium Theater. Brighton Beach. You see it. We start seven. Very good band. Leader has gigs coming up. I tell him you coming.”

“Eets beeg place. Millennium Theater. Brighton Beach. You see it. We start seven. Very good band. Leader has gigs coming up. I tell him you coming.”