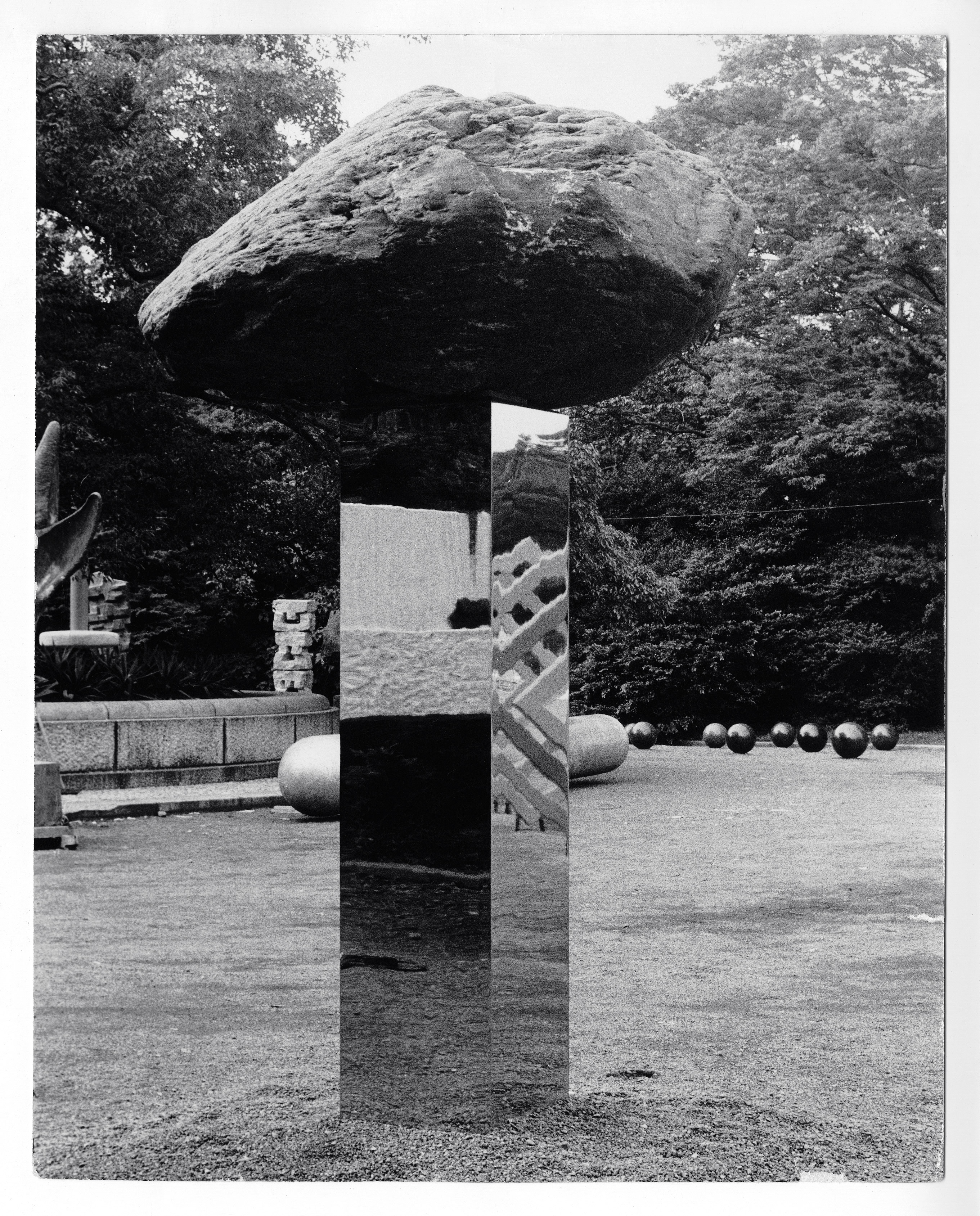

Nobuo Sekine. Phase of Nothingness, 1969-70.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Akim Reinhardt

Several co-workers, all of whom have Ph.D.s. An old friend who’s a physicist. Scads of family members of both blue and white collar variety. Numerous neighbors. And of course the well dressed, kindly old women who occasionally show up at my door uninvited, pamphlets in hand.

Several co-workers, all of whom have Ph.D.s. An old friend who’s a physicist. Scads of family members of both blue and white collar variety. Numerous neighbors. And of course the well dressed, kindly old women who occasionally show up at my door uninvited, pamphlets in hand.

One can point to general trends about the powerless, the vulnerable, and the less-educated as likelier to believe in God than those full of book learnin’ or living the good life. But But when the vast, vast majority believe, the believers represent a thorough cross-section of society. And so my daily existence, and that of many if not most atheists, involves sharing interactions and ideas with all sorts of people, wealthy and poor, old and young, male and female, well educated and not, who embrace magical thinking to one degree or another. Who believe either quite vividly or a bit vaguely in a supreme, celestial being or force with at least some degree of sentience and even an agenda. A god who sees and hears us. And perhaps a soul or spirit within in us that lives on after our bodies have given out, some ethereal expression of immortality, some mechanism of continuity after this go-around is done, some medium of transcendence into a heavenly (or hellish) destiny, or perhaps into another corpus, whether animal or human yet unborn, and from there a fresh start.

We, the atheists, the ones who, if you are anything like me, cannot believe even if we desperately want to because we find it patently unbelievable, are a small minority around the world. Here in the Untied States we number a scant 3%. All around us, a great majority run the gamut: agnostics (only 4%) who may one day end up like us; a growing number of people who just don’t think about it all that much until they end up in some proverbial foxhole; conscious believers, such as my friend the physicist, who might be like us in countless other ways; hardier believers hungrily gulping up the magic; and ever up the scale eventually peaking with a small number of badly broken and certifiably insane people who think they themselves are this or that saint or such and such deity. Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

One God, One Farinelli…

Stepping onto the stage, the singer draws in a long breath as he gazes out across the audience. For a moment, he is blinded by the light of innumerable candles. So lavishly lit, it is a miracle that the theater didn’t burn down more than it did over the years. Over a hundred boxes rise up in six tiers in front of him; each box with a mirror affixed on the front reflecting the twinkling light of the two candles placed on either side. The singer can just make out the bejeweled king and queen sitting in their royal box with its gigantic gold crown hovering above. This was the Teatro di San Carlo in the Kingdom of Naples, considered during the 18th century to be the greatest opera house in the world. And on this night, people had come from far and wide to hear Farinelli sing— Farinelli, the famed castrati singer, who drew great crowds and commanded princely sums wherever he performed.

But what a price he had paid to stand on this stage.

The deplorable practice of mutilating young boys to preserve their adolescent voices began in Italy as early as the 12th century. But castrati voices are something we associate most closely with 17th-18th century Baroque music. At that time, women were not allowed to sing in church or on stage in the Papal States, and so the practice began of seeing men singing the roles of women. But this was not like in Japan in Kabuki theater, where you still see men exclusively performing the roles of women; for in Italy these were not men dressed up as women –but rather were those who had undergone castration as children. The church alone cannot explain the huge popularity of their voices throughout Europe. In Naples or London, for example, women had never been banned from appearing on stage, and yet castrati regularly appeared alongside female sopranos.And they were wildly popular. Rock stars, is how we would describe them today. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Robert Fay

Kit Moresby, the enigmatic heroine of Paul Bowles’ novel The Sheltering Sky sits in a café in a French colonial city in North Africa. It’s 1949 (or thereabouts) and on the terrace Arab men wearing fezzes drink mineral water and swat flies. Kit and her American companions have just arrived by freighter and they sip Pernod and discuss their initial impressions. They are planning on traveling into the Bled, the vast interior, where they hope to find lands and people untouched by the war and the contaminates of European civilization.

These three are the opposite of the “ugly American” stereotype of the post-war era. They are pessimistic, worldly and bored with America. If anything, their Americanness is revealed in their unwillingness to accept that life and suffering could possibly be synonymous. They are world-weary Bohemians who recognize the America of the 1950s will be a consumer-orientated project. These characters are, in a certain sense, proto-Beats, and in fact the actual Beat writers, men like William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac admired Bowles and eventually befriended him.

“It seems as though there might be some place in the world they could have left alone,” Kit says. She is a woman of omens. A person of great strength, yet because of the restraints of the era, must admit “other people rule my life.” She wants to truly live, to push aside the veil separating her from raw experiences, but she is fearful and superstitious. “The people of each country get more like the people of every other country,” she says. “They have no character, no beauty, no ideals, no culture—nothing, nothing.” Read more »

by Dave Maier

Ted Chiang’s (very) short story “What’s Expected of Us” (collected in his recent Exhalation) tells of an unusual device called a Predictor:

Its only features are a button and a big green LED. The light flashes if you press the button. Specifically, the light flashes one second before you press the button.

Most people say that when they first try it, it feels like they are playing a strange game, one where the goal is to press the button after seeing the flash, and it’s easy to play. But when you try to break the rules, you find that you can’t. If you try to press the button without seeing a flash, the flash immediately appears, and no matter how fast you move, you never push the button until a second has elapsed. If you wait for the flash, intending to keep from pressing the button afterward, the flash never appears. No matter what you do, the light always precedes the button press. There’s no way to fool a Predictor.

This is because the device sends a signal back in time, flashing at time t if and only if you press the button at time t + 1 second. Your push causes the flash, even though the flash appears first. No guesswork necessary; that’s how the device works.

In the story, many people, including the narrator himself, take the Predictor to be a demonstration of the unfortunate fact that they have no free will, and that, as the narrator puts it, “their choices don’t matter.” I can see why they think this, but I’d like to try to undermine that intuition here if I can, since it underlies much of the non-science-fictional debate about free will and physical reduction that we started last time. (Note: we will not be solving the free will problem here today, nor do I claim originality for this line of thought; on the other hand, all infelicities in the exposition are my own.) Read more »

In January of this year I was walking along the main road in the small village of Klerant up in the mountains above Brixen, in the Südtirol, when I heard a rooster crowing loudly. I looked up to see these two posing perfectly for a portrait in this window. One can also see part of the steeple of the village church in the reflection in the window.

by R. Passov

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.

One day I watched a conversation that confirmed my suspicions. Johnny had returned from somewhere Big Greg had sent him. He danced as he spoke, swinging a long arm up over his head, around and down.

“The dude’s wife’s right there. I grab his guitar and bust it all up. Broke that shit right in front of em. Yeah, I said, this is what I mean.”

He had tried to be violent but in the retelling I could see his heart wasn’t in it. “Davy doesn’t play guitar,” Big Greg said. “Where the hell did you go?”

To the wrong house.

He was tall but thin. Black, but feline. Not black like the men he hosted when he had his apartment. Men who turned the living room into a weight room, sitting on benches all day doing curls, out of prison but still in. Johnny wasn’t like that.

Though I didn’t know of Lou Reed, didn’t have a radio, or a stereo or even a record, Johnny belonged in a Lou Reed song. He wanted to be a colored girl.

I know that now. Then I spied his gentleness, his out of place-ness, his role playing, that he lived between lives. Someone with you and somewhere else at the same time. Something children see but not adults.

He and Big Greg wore their green shirts, sleeves cut off, Alexander and Diles marked in black over their hearts. I decided to believe their experience in war freed them of law. Read more »

I was improvising before I’d learned the word, but I wasn’t systematic about it until years later. I suppose for a time the word had a bit of a mystique about it, as it does for many. After all, the norm in Western musical practice has been to read music that someone else, the composer, had written. The composer is the authority; you are a mere conduit; and improvising, where you (shudder) make it up yourself, that’s VERY mysterious.

* * * * *

You mean, no notes in front of you. Just make it up?

Yes.

And it comes out OK?

Sometimes, sometimes not. It depends.

Isn’t that very brave and dangerous?

No. Do you speak from a script?

No.

Well then, there you have it. Don’t need a script for music either.

* * * * *

I started taking music lessons when I was ten years old. My earliest teachers taught me to read music, and only to read music. So that’s what I did. But at some point, I forget just when, I decided I wanted to play simple tunes that weren’t in lessons. I decided, well, I’ll just have to figure out how to do it. I do remember that, when I was in sixth grade, I was particularly taken with the theme song to a series that played on Walt Disney’s Sunday night TV show. I forget the name of the series, but it was about mountain men and the song had wistful lyrics about living in the mountains. Read more »

by Bill Murray

What you pay attention to depends on where you are.

What you pay attention to depends on where you are.

“In an old city, a tourist hears the rumble of wheels over cobblestones that the native does not and notices sound bouncing differently between walls more tightly constructed than in spacious American cities.” – Alexandra Horowitz

She’s right. With the clatter of hoofs from horse-drawn carriages-for -hire in the tourist-center of Dresden a couple of weeks ago, you could see it; the locals plodded on; the tourists perked up and searched out their source.

With sound, personal space is different in different places, too. On the 13th floor of a 21-floor building in Ho Chi Minh City in April, we might as well have been invited guests in the skybar above us. Live Viet Pop invaded our personal earspace the same way a plane flies over your house’s airspace. With utter impunity.

Something else about listening: silence is a sound of its own. After a month in Vietnam, the silence of the Finnish lakeshore, where we are now, is music I was overdue to hear.

Not that it’s entirely silent. Birch leaves rustle like fresh linen sheets. Gulls shriek and shriek at constant calamities. Is there a more easily affronted creature?

On our waterfront this year we have three flocks of ducks, a grebe with an astonishing trail of a dozen babies, and a swan couple with a brood of five. They are doing what they do, growing kids each day, adults teaching kids how to be water birds. Read more »

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Everybody knows what real-world political disagreement is like: shouting, name-calling, dissembling, browbeating, mobbing, and worse. As it is practiced, deliberation in actual democracy has little to do with collective reasoning about the common good; it’s instead a constrained, but nevertheless ruthless, struggle for power. Notice, however, that hardly anyone embraces this condition. When people describe democracy in such terms, they are most often complaining. But notice that lamentations over the cut-throat nature of politics make sense as criticisms only against the backdrop of an aspirational alternative. Our forthcoming book, Democracy in a Divided World, develops a democratic ideal worth aspiring to. According to that ideal, democracy is a system where political equals govern together by means of well-run political argument.

This ideal is admittedly distant, but it hasn’t been plucked from thin air. Despite the condition of our democracy, citizens and officials alike hold one another to high standards of civil conduct. When the President characterizes those he perceives to be his critics as “very dishonest people,” he appeals to the public virtue of honesty. Charges of bias uphold the related public virtue of evenhandedness. When one criticizes a news organization for being slanted, one is insisting upon a public virtue of fairness. Note, too, that it is common now for the word “partisanship” to be used as a criticism; when one official charges another with being “partisan,” she is claiming that the other is dogmatically committed to a party line. Such charges uphold the ideal of proper argumentation. The fact is that real world politics, warts and all, is still animated with the aspiration to democracy as a system of well-run argumentation.

This occasions a puzzle. We all embrace the same democratic ideal of well-run argument and joint governance. And no one wholeheartedly approves of the political status quo. So why is our democracy so dysfunctional? Call this the debasement puzzle. Read more »

by Anitra Pavlico

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5 trillion. Average debt per student is $37,000, and over 44 million Americans have student loan debt. Default rates are rising. The situation is unsustainable on a grand scale, and on a personal scale is causing millions of people untold stress. At the same time, the prospect of debt cancellation seems too good to be true.

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5 trillion. Average debt per student is $37,000, and over 44 million Americans have student loan debt. Default rates are rising. The situation is unsustainable on a grand scale, and on a personal scale is causing millions of people untold stress. At the same time, the prospect of debt cancellation seems too good to be true.

There are some interesting parallels to the housing market of last decade and some key differences. (This is a non-economist’s view from someone who has worked on litigation arising from defective mortgage-backed securities.) One parallel is that demand has pushed the costs of college higher and higher, just as it did in the housing market–and another similarity is that easy credit has pushed costs higher. Financing creates a sort of reality gap between cost of the goods and ability to repay. If you have to save for school in advance, you will be keenly focused on rising costs of your end goal. If costs rise too quickly, you will never be able to save enough, and you won’t be able to go. If costs rise quickly but you will get financing for whatever part you can’t afford, you are not necessarily so focused on the ultimate cost. Whatever it is, you will be attending the school. Some observers have blamed the federal government for guaranteeing almost all student loan debt, thus making lending to students a very attractive proposition. It is painfully similar to the government’s magnanimous emphasis on expanding homeownership. Read more »

saucers in space, a flock,

a green gaggle of water lilies

upon cool liquid too precise

to be Monet’s, too crisp

but let me lie upon your quietude

let me swim among your green voids

let me calculate the diameters of your circles

with the calipers of my eyes

yes even the yellow renegades you harbor

how they lie within your circle of still

simultaneously blaring sun

from the deep black of your pond

which has also given us

with your cool rectitude

a glimpse of sky

Jim Culleny

7/9/19

Photo by S. Abbas Raza: Water Lilies at Lido in Brixen, South Tyrol, July 9, 2019.

by Katrin Trüstedt

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics.

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics.

NGO rescue boat Captain Carola Rackete was arrested after forcing her way into the port of Lampedusa, in defiance of a ban by Italy’s far-right interior minister, Matteo Salvini, bringing 40 migrants and refugees she had rescued from the sea off Libya to the Italian island. The young activist’s two-week standoff with the far-right minister Salvini and Italian authorities is the stuff of political mythmaking. La Capitana – as she is called in the Italian News in provocation of Salvini who likes to be called Il Capitano – gives the European Migration Crisis and the resistance to its exclusionary politics a face. What she has come to stand for is of mythical proportion: On the cover of Der Spiegel, she is featured as “Captain Europe,” and in various other media she has been called a modern-day Antigone. Just as Antigone resisted the command of Kreon, the official sovereign and legal authority, by reference to a higher law, Rackete opposed the directives of Salvini in the name of international maritime law. And just as Antigone’s standing up to Kreon by burying her brother has become the material for an ancient myth, Rackete’s face off with Salvini lends itself for contemporary mythical elevation. Her story evokes a mythological battle between good and evil, right and wrong, justice and injustice, law and counter-law in the political arena of our times. It is the story of an underdog, standing up against overwhelming forces to do the right thing for those who are rightless. Read more »

by Niall Chithelen

When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.

When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.

This I did while waiting for my rescheduled connecting flight. I contemplated, for hours, my life, my mistakes, my goals. I thought about how I had gotten to where I am today. I thought about what it is that, to me, means greatness; I thought about what it is that makes a coffee taste good and why it was absent from each coffee I consumed that day.

The airport was not too full, and so I had space to think. I was in Frankfurt, one of Germany’s largest cities, near the geographic center of Europe. Europe has in recent years been roiled by the rise of illiberal so-called “populists,” and these developments have given rise to serious questions about the politics of our time—are these new far-right and far-left movements primarily responses to globalization and financialization, do they stem more from existing social and political currents? Should I have put more sugar?

At this point, five or so hours into my time at Frankfurt, I had been thinking intently for hours, a hum emanating from my now slightly vibrating frame. My eyes were laser-bright with analytical fervor. How many cups of coffee is too many? I was approaching this number. Read more »

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

“Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair, so that I may climb the golden stair:” the witch sings to the blonde Rapunzel imprisoned in her tower.

In a legend, Rudabeh, the dark-haired princess of Kabul lets her hair down like a rope for prince Zal to climb up to her tower. She has eyes “like the narcissus and lashes that draw their blackness from the raven’s wing.” Her name is Rudabeh, “child of the river.”

Rapunzel is Brothers Grimms’ nineteenth century retelling of Persinette (1689), which is surmised to be an adaptation of the millennia old Persian legend of Rudabeh, famously recast in Shahnameh, the Persian masterpiece written by the poet Ferdowsi in the eleventh century. Ferdowsi’s lofty praise in his poem set a high bar for the artists who painted the legendary beauty Rudabeh: “about her silvern shoulders two musky black tresses curl, encircling them with their ends as though they were links in a chain.”

The links between such stories from the East and the West emerged first through startling common etymologies in everyday language, songs and stories. As a child tuned in to the world of words, I asked for stories when my mother combed my hair, and caught images and contours of sound in fairy tales in English, the text running from the left to the right and stories of the Alif Laila (One Thousand and One Nights) and Qissa Chahaar Darvish (The Story of the Four Dervishes) in Urdu from the right to left. Read more »

Leonardo Da Vinci. St. Jerome Praying in The Wilderness, begun Ca. 1482; unfinished.

“…The painting shows St. Jerome at prayer at the end of his life, a hermit in the wilderness, alone save for his lion companion—a common Renaissance subject. And yet it stands alone in its deeply moving, intimate depiction of the penitent saint in a moment of private reverie. As Jerome stares up at his crucifix, his spiritual struggle is plain to see, even though many passages of work show little more than the ground preparation on the wood panel, with hastily sketched outlines.”

“A close examination of the paint surface reveals the presence of Leonardo’s finger prints in the upper left portions of the composition, … Leonardo used his finger to distribute the pigments and to create a soft focus effect in the sky and landscape.”

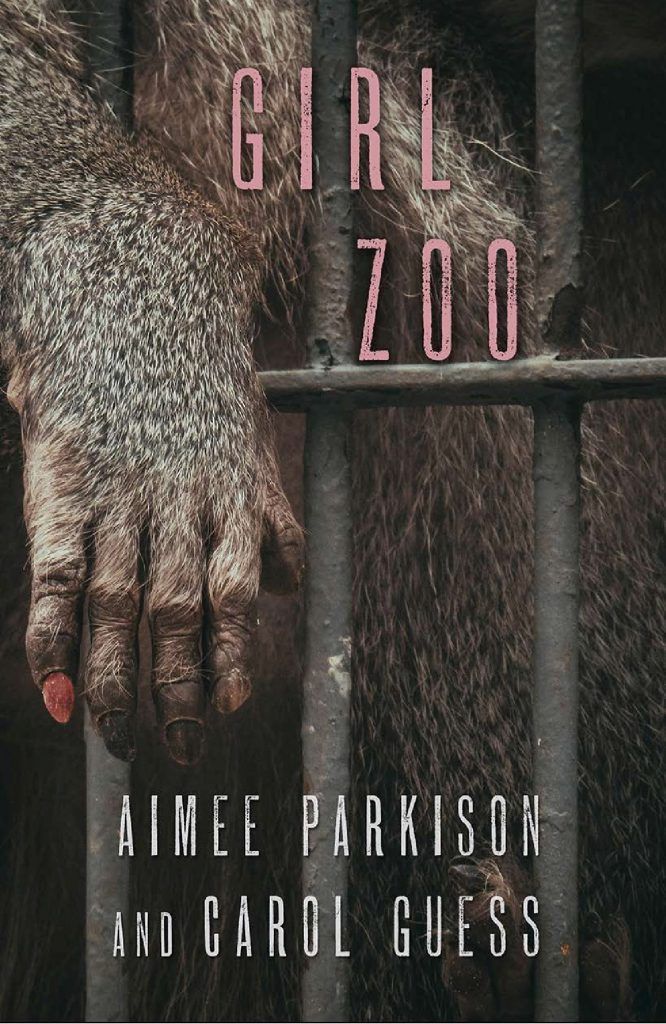

Andrea Scrima: Girl Zoo, which has just been published by the FC2 imprint of the University of Alabama Press, is a collection of stories that takes contemporary feminist theory on an odyssey through the collective capitalist subconscious. Scenes of female incarceration are nightmarish, hallucinatory: each story exists within its own universe and operates according to its own set of natural laws. But while there’s a fairy-tale quality to the telling, none of these stories departs very far from the everyday experience of institutionalized sexism: the all-too-familiar is magnified just enough to reveal its inherently devastating proportions.

Aimee, Carol, I wonder if we could begin by talking about the collaborative process. How did the idea come about to write a book together?

Aimee Parkison: As an artist, I’m always trying new things. I have a wide range and want to expand and explore. My creative process is vital to the way I experience the world. I like the excitement of a new project, a new idea. I write all sorts of stories, from flash fictions to long narratives, from experimental to traditional, from realism to surrealism. Some of my fictions are character-based and others more conceptual. I often focus on the lives of women and am known for revisionist approaches to narrative and poetic language. My writing is often categorized as experimental or innovative. I’ve published five books of fiction, story collections, and a short novel. I’ve been published widely in literary journals. Among my previous books are Refrigerated Music for a Gleaming Woman (FC2 Catherine Doctorow Innovative Fiction Prize) and a short novel, The Petals of Your Eyes (Starcherone/Dzanc). I admire Carol’s writing and had interviewed her for a couple of articles I was writing for AWP’s The Writer’s Chronicle magazine. A year or so after the interview, she emailed me, inviting me to do a collaboration.

Carol Guess: My approach to writing came through music and dance. Years ago, I studied ballet and moved to New York to try to make a career in that world. Obviously that didn’t happen, but my early experience with failure made me determined to be good at something else! I’d always written for pleasure, so I began taking my writing more seriously, initially focusing on poetry. I did my MFA in poetry; I’ve never actually taken a class in fiction writing. I put my first novel together as an experiment. I wanted to teach myself how to write a novel, and so I did. Since then I’ve published twenty books, each one an experiment and a challenge. I’ll ask myself, “What would happen if …” and then set out to answer my own question. Read more »

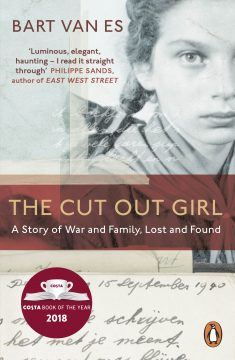

by Adele A Wilby

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

Bart Van Es’s The Cut-Out Girl is the winner of the 2018 Costa literary prize. It is an admirable winner: the story of Lien de Jong, and how she experienced her childhood as one of the Netherlands’ 4000 ‘hidden’ Jewish children during the Nazi occupation of the country in World War II, and her life thereafter. Lien and her immediate family were part of the 18,000 Jews who resided in The Hague in 1940, out of which only 2,000 survived the war.

The book offers revelatory insights into the precarious existence of a Jewish child constantly exposed to the danger of round-ups by Nazi troops and the possibility of betrayal of her location by local Nazi sympathisers. Inevitably her story is interconnected with the families who provided her refuge, in particular the Van Es family.

Had Oxford academic Bart Van Es not been curious about the ‘lost’ member of his family, Lien, it is doubtful that her story would ever have come to light, and the experiences of a Jewish child caught up in a struggle to survive would have been lost to the world. Van Es’s journey of discovery to learn of the ‘lost’ ‘family’ child not only leads to reconciliation with the descendants of the Van Eses who provided the refuge, but to closure for both Lien and the Van Es family saga. Read more »

by Brooks Riley