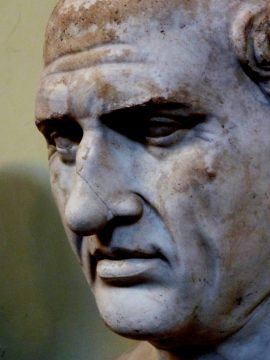

by Emrys Westacott

When I studied philosophy as an undergraduate in the UK in the late seventies, Nietzsche was pretty much off limits. None of his texts were included on any of the course syllabi. We devoted an entire term to Gilbert Ryle’s The Concept of Mind, but not even during a year-long course on Phenomenology and Existentialism was Nietzsche so much as mentioned. Such was the analytic insularity of academic philosophy in Britain at the time.

Things have changed since then. Today, in any book store with a genuine philosophy section, the shelf space occupied by books by or about Nietzsche is likely to be greater than that devoted to any other thinker. There are now reliable English translations of all his published works along with his notebooks and letters. And philosophy students will usually have many more opportunities to encounter his texts in the course of their studies.

Exactly why Nietzsche’s star has risen so high over the last few decades is a complex question. Many factors could be cited. His notorious association with Nazism was shown (by Walter Kaufmann and others) to be largely based on a misrepresentation. His seminal ideas about morality, religion, human nature, art, culture, truth and knowledge increasingly seemed to chime with the times. A broadening conception of philosophy within academic departments made room for a writer who had previously attracted the attention of literati rather than philosophers.

But more important than these, I believe, are three further reasons. Read more »

In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame.

In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame.

The basic details of the story are known to almost everyone: a Malaysian Airlines flight simply disappeared one night in March 2014 and, more than five years later, the plane has still not been found.

The basic details of the story are known to almost everyone: a Malaysian Airlines flight simply disappeared one night in March 2014 and, more than five years later, the plane has still not been found. On Sunday, May 17, 2015, there was a Lutheran church service in Delmont, South Dakota. Just one. A week earlier—on Mother’s Day—there had been two, one at Hope Lutheran, another at Zion Lutheran. At around 10:45 that morning, during Sunday school at Zion Lutheran, a tornado had ripped through the town, taking out 40 homes and sucking the roof off of Zion Lutheran. A woman later told us there was a pipe organ “trapped” inside, as if it was a living victim of the storm.

On Sunday, May 17, 2015, there was a Lutheran church service in Delmont, South Dakota. Just one. A week earlier—on Mother’s Day—there had been two, one at Hope Lutheran, another at Zion Lutheran. At around 10:45 that morning, during Sunday school at Zion Lutheran, a tornado had ripped through the town, taking out 40 homes and sucking the roof off of Zion Lutheran. A woman later told us there was a pipe organ “trapped” inside, as if it was a living victim of the storm. Sughra Raza. “Steep-le-chase!”; June, 2019, Rwanda.

Sughra Raza. “Steep-le-chase!”; June, 2019, Rwanda. The relation between mind and matter is a perennial philosophical conundrum for a reason. If the workings of the mind depend too much on the physical material that seems to house it, then it can be hard to see how there’s conceptual room for human agency. On the other hand, if they don’t depend on it at all, then it’s hard to understand why such things as brain injury or the ingestion of this or that chemical substance should have any effects at all, let alone the reliably predictable effects that often result. Something’s gotta give!

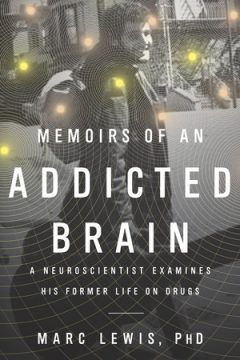

The relation between mind and matter is a perennial philosophical conundrum for a reason. If the workings of the mind depend too much on the physical material that seems to house it, then it can be hard to see how there’s conceptual room for human agency. On the other hand, if they don’t depend on it at all, then it’s hard to understand why such things as brain injury or the ingestion of this or that chemical substance should have any effects at all, let alone the reliably predictable effects that often result. Something’s gotta give! It is a big cross. A really big cross. Forty feet in height, made of granite and concrete, The Bladensburg Peace Cross stands tall and straight for all to see.

It is a big cross. A really big cross. Forty feet in height, made of granite and concrete, The Bladensburg Peace Cross stands tall and straight for all to see.

Many years ago, my father and I were at a backyard BBQ in New Jersey hosted by someone we barely knew, I think they were somehow connected to my step-mother. At some point, the topic of flag burning came up and, before we knew it, we were engaged in an extremely heated debate on what patriotism actually means (I believe that the rights the flag stands for include the right to burn it). The debate ended up with a large group of people holding beers and hot dogs decrying the liberal anti-Americanism of the two of us. Not the best way to spend a summer afternoon. These days, it’s possible, in fact too easy, to repeat the unpleasantness of that afternoon all the time on social media. I try my best to steer away from the soul sucking void that is having debates on Facebook with friends of friends. We all have those people in our lives with whom we have a moral or political disconnect and that those people will sometimes make comments that will inflame our more simpatico friends may be inevitable, but doesn’t have to be engaged with and perpetuated. Such debates don’t change hearts and minds. Full disclosure, I admit, sometimes I don’t follow my own advice here as well as I should, but I try.

Many years ago, my father and I were at a backyard BBQ in New Jersey hosted by someone we barely knew, I think they were somehow connected to my step-mother. At some point, the topic of flag burning came up and, before we knew it, we were engaged in an extremely heated debate on what patriotism actually means (I believe that the rights the flag stands for include the right to burn it). The debate ended up with a large group of people holding beers and hot dogs decrying the liberal anti-Americanism of the two of us. Not the best way to spend a summer afternoon. These days, it’s possible, in fact too easy, to repeat the unpleasantness of that afternoon all the time on social media. I try my best to steer away from the soul sucking void that is having debates on Facebook with friends of friends. We all have those people in our lives with whom we have a moral or political disconnect and that those people will sometimes make comments that will inflame our more simpatico friends may be inevitable, but doesn’t have to be engaged with and perpetuated. Such debates don’t change hearts and minds. Full disclosure, I admit, sometimes I don’t follow my own advice here as well as I should, but I try.

As early as 1293 a Swedish marshal built a castle in Vyborg, now Russian. The castle traded hands repeatedly between the Swedes and the then Republic of Novgorod. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and loss of fortresses in Narva, Tallinn and Riga,

As early as 1293 a Swedish marshal built a castle in Vyborg, now Russian. The castle traded hands repeatedly between the Swedes and the then Republic of Novgorod. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and loss of fortresses in Narva, Tallinn and Riga,