by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Tim Sommers

In the first scene of the first episode of “The Wire”, McNulty asks the Corner Boy who witnessed the murder of his friend “Snotboogie”, for stealing the money from the pot in a crap game, why they let Snotboogie play, since he always tried to steal the money. The Corner Boy replies, “Got to. This is America, Man.”

This is America. Everybody gets to play. More than that, everybody gets an equal, or at least a fair, shot. Everybody deserves equal opportunity. Justice itself demands that we strive for equality of fair opportunity. Right?

I’m not sure. But I think not. I think equality of opportunity is a bad idea – all the worse because it seems so obviously like a good idea.

But how can one deny that we should strive for equality of fair opportunity? Here’s one way. If you think property rights override everything else, and you always have the right to do what you will with your property no matter what; then it follows that you don’t have to hire gay people if you don’t want to and you don’t have to serve people of color at your restaurant if you don’t want to. This is how Rand Paul, who fancies himself a libertarian, got in trouble – questioning the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

I have no sympathy for this way of being against equal opportunity. Of course, nondiscrimination, what is often called “formal” equality of opportunity, is a requirement of justice. I just don’t think we should call that equal opportunity. I would prefer that we treat the right not to be discriminated against as a basic liberty on par with free speech or the right to vote – maybe, even as part of, or an extension, of equality before the law. Read more »

by Adele A. Wilby

Shade from the mango tree blocked out the light to my room. I felt into the darkness of my wardrobe, and as I did so I hoped a confused cobra had not gotten lost and slithered in and curled itself up and taken temporary residence in a corner amongst my clothes. I walked my fingers down my pile of shirts until I recognised the texture of the one I wanted to wear, and dragged it out. Nervous excitement whirled around in my stomach. Today could be the day, I thought, as my fingers fumbled to button up my shirt. Perhaps I was being foolish: perhaps I shouldn’t go.

‘Let’s go. Let’s go. It’s getting late,’ shouted the driver, as he gestured to the group of guerrillas languishing on the veranda waiting to get into the vehicle for their ride home. The murky green of the pick-up made it look more like a battle tank than a transport vehicle.

The four young men threw their carry bags into the back and clambered onto the vehicle and perched themselves on the seat. The cool breeze would fan their hair and their faces as they made their way along to their homes, and from where they could be on guard also. They held their Kalashnikovs tight and upright between their legs. They knew their lives depended on keeping a firm grip of that rifle as they passed through the jungle road where the known that lurked amongst the tangled foliage posed as great a threat as the unknown. Read more »

Self-portrait in a reflection in a passing train window, while another train goes the other way behind me, at the train station in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, in May of 2019.

by Brooks Riley

Racing down a German autobahn at impossible speeds is like running past a smorgasbord when you don’t have time to eat. Exit signs fly by, pointing to delicious, iconic destinations that whet the appetite but that one has no time for: Hameln, Wittenberg, Quedlinburg, Eisenach, Erfurt, Altenburg, Jena, Weimar, Dessau—markers of histories whose tentacles reach into the present in ways that belie their sleepy status on the map. You suppress the urge to slow down and take the off-ramp instead of moving right along to a big-city destination You opt to remain on the asphalt treadmill with arrival anxiety, telling yourself that one day you will take the time to explore all this, just not right now.

Racing down a German autobahn at impossible speeds is like running past a smorgasbord when you don’t have time to eat. Exit signs fly by, pointing to delicious, iconic destinations that whet the appetite but that one has no time for: Hameln, Wittenberg, Quedlinburg, Eisenach, Erfurt, Altenburg, Jena, Weimar, Dessau—markers of histories whose tentacles reach into the present in ways that belie their sleepy status on the map. You suppress the urge to slow down and take the off-ramp instead of moving right along to a big-city destination You opt to remain on the asphalt treadmill with arrival anxiety, telling yourself that one day you will take the time to explore all this, just not right now.

That was my first brush with Dessau, as I was rushing somewhere else. I knew that it was a home of the Bauhaus and that it had been heavily bombed during the war—more than half of it destroyed. In the distance I could see the amorphous outline of a town I wanted to visit someday.

Destiny must have listened. For reasons that had nothing to do with architecture or the Bauhaus, I ended up spending time in both Weimar and Dessau—the two main locations of a movement that exerted an immeasurable influence on the future of architecture worldwide, and occupied an inordinate amount of downtime in my imaginary life. Read more »

by David Introcaso

Two weeks ago the 9th US Circuit Court heard oral arguments in the Juliana v. the US case filed in 2015 by 21 children who petitioned the federal court to require the government to protect their Constitutional rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness by addressing the climate crisis. In its defense the US argued the plaintiffs have “no fundamental constitutional right to a stable climate system,” or a “climate system capable of sustaining human life.”

Two weeks ago the 9th US Circuit Court heard oral arguments in the Juliana v. the US case filed in 2015 by 21 children who petitioned the federal court to require the government to protect their Constitutional rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness by addressing the climate crisis. In its defense the US argued the plaintiffs have “no fundamental constitutional right to a stable climate system,” or a “climate system capable of sustaining human life.”

It appears plaintiffs’ lives are in fact not protected. In a just-published essay in The New England Journal of Medicine by Harvard’s Dr. Renee Salas and her colleagues concluded, “climate change is the greatest public health emergency in our time and is particularly harmful to fetuses, children and adolescents.” This is because recent reports including the US’s National Climate Assessment, the United Nations’ (UNs’) Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) “Global Warming of 1.5ºC” and Lancet’s “Countdown on Human Health and Climate Change” all describe in agonizing detail rapid atmospheric warming from currently 1º Celsius to 2º Celsius within the next few decades are causing increasing flooding, wildfires, disease, starvation, forced migration and war. According to a recent Carbon Brief study, the carbon budget of a child born today will have to be one-eighth that of one born in 1950 if they want to live in a world that is less than 2º Celsius warmer.

The Juliana case along with numerous related others was decades overdue. Since Ronald Reagan, the Republican Party has denied or worked to undermine the life-extinguishing effects of atmospheric warming. President Trump summarized his recent 90-minute discussion on the topic with Prince Charles by stating, “the US right now has among the cleanest climates.” He refused to recognize climate science stating, “I believe there’s a change in weather and I think it changes both ways.” Incoherent rhetoric aside, the US Geological Survey recently decided to project climate crisis impacts only through 2040 rather than to the end of the century to avoid detailing the worst impacts of Anthropocene warming. Read more »

by Emily Ogden

Because I wanted to write about something I believe in, my topic today is irony.

The alert reader is already asking, can you believe in irony? The ironist is widely supposed to be a person who doesn’t really believe in anything. Disavowing her attachments as soon as she forms them, holding nothing sacred, she occupies a stance of cool detachment. I don’t think this picture is right. Far from detaching us from the world, irony allows us at once to hold fast to our attachments and to hold them at a distance; to be convinced about our convictions and to be willing to question them.

Such a definition of irony doesn’t necessarily change the ironist’s outward aspect. Go ahead and imagine the same cool customer as before, if you like. But reconsider what might lie behind her performance of detachment. She doesn’t simply say the opposite of what she means for comic effect, as a sarcastic wit might do. Instead, the ironist means everything she says and more besides. If I say that irony is the one thing I really and truly believe in, for example, I’m deliberately invoking the conflict we think exists between irony and belief. I invoke that conflict not to cancel the belief with the irony, but to show that these attitudes can survive their mutual antagonism. Not all conflicts have to end in the extermination of one combatant. Read more »

…—for Catherine Regec Mraz

this is how I most

remember her I’d have been

maybe eight, I open the door

to her house and hear

the latch click,

clock tick

we have tea at her table

I ask for grandpa’s cup

which she brings from her pantry shelf

and sets upon the table

pours hot water into its metal

beige-enameled steam-blessed bowl

with light-green rim

adds teabag a little sugar

I stir and sip as she in

Slovak-embellished English,

smiling, asks about my day and life

in the fragrant atmosphere

of chicken boiling in the soup

she made so well,

and calls me

Jeemy

………… I have that cup

—when the house was sold

after they’d gone we were gifted

with a last-chance tour

of rooms so simply lived in

and there’s my grandfather’s cup

on the shelf where he’d left it

near his wife’s tea and sugar

and

as was anciently told

I asked and it was given

Jim Culleny

6/7/19

by Joan Harvey

What made him a great poet was the unprotesting willingness with which he yielded to the ‘curse’ of vulnerability to ‘human unsuccess’ on all levels of human existence—vulnerability to the crookedness of the desires, to the infidelities of the heart, to the injustices of the world. —Hannah Arendt on Auden[i]

Sometimes we have to do the work even though we don’t yet see a glimmer on the horizon that it’s actually going to be possible. —Angela Davis

. . . something undaunted wants to move no matter how inauspicious the prospects, advance no matter how pained or ungainly. —Nathaniel Mackey

A man goes door to door, wearing his murdered son’s shoes, to ask voters to make him their state representative. His son, Alex, 27, had been gunned down in the Aurora theater shooting. The man, Tom Sullivan, is elected, even in a very conservative district, and shortly afterward sponsors an Extreme Risk Protection Bill to give law enforcement the ability to temporarily remove guns from people having a mental health crisis. He wears his murdered son’s leather jacket when he speaks on behalf of the bill. It’s too late for his son. But, he says, “I’m not doing this for Alex and my family, I’m doing it for yours. Watching your child’s body drop into the ground is as bad as it gets, and I’m going to do everything I can to make sure that none of you have to do that.” The bill passes. And then comes the campaign to recall Sullivan, organized by Rocky Mountain Gun Owners, a group who claims the NRA is a sellout, and whose executive director will get a cut of every dollar that the group raises. Republican Patrick Neville, Colorado House minority leader, is helping to organize these recalls.[ii] And this is only one of nine recalls proposed in Colorado.

In the film Knock Down the House, the three women profiled along with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez all ran based on their experience with systemic violence. Amy Vilela of Nevada lost her daughter when a hospital refused to admit her because she didn’t have insurance. Paula Jean Swearengin of West Virginia lost many friends and family to cancer caused by coal mining. Cori Bush of St. Louis lived in close proximity to Ferguson. All these women ran tough campaigns against entrenched incumbents and all three lost their races. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Mid-day Still. Chitwan Forest, Nepal, 2017.

Digital photograph.

by Jeroen Bouterse

The Big Bang Theory has been one of the most successful sitcoms in TV history. Last month it ended. In many ways, it ended a long way from where it had begun; many commentators have noticed how the show has evolved together with cultural norms in the past decade. Its first seasons milked gender-stereotypes to an embarrassing extent; later, the main cast included more women, and generally changed its tone on gender and science – even making it a theme in several episodes.

The Big Bang Theory has been one of the most successful sitcoms in TV history. Last month it ended. In many ways, it ended a long way from where it had begun; many commentators have noticed how the show has evolved together with cultural norms in the past decade. Its first seasons milked gender-stereotypes to an embarrassing extent; later, the main cast included more women, and generally changed its tone on gender and science – even making it a theme in several episodes.

Still, a sitcom like BBT needs its stereotypes, and BBT’s idea of geek culture did remain stereotypical; if not on the level of gender, then in other ways that I want to explore here. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

The Doomsday Scenario, also known as the Copernican Principle, refers to a framework for thinking about the death of humanity. One can read all about it in a recent book by science writer William Poundstone. The principle was popularized mainly by the philosopher John Leslie and the physicist J. Richard Gott in the 1990s; since then variants of it have have been cropping up with increasing frequency, a frequency which seems to be roughly proportional to how much people worry about the world and its future.

The Doomsday Scenario, also known as the Copernican Principle, refers to a framework for thinking about the death of humanity. One can read all about it in a recent book by science writer William Poundstone. The principle was popularized mainly by the philosopher John Leslie and the physicist J. Richard Gott in the 1990s; since then variants of it have have been cropping up with increasing frequency, a frequency which seems to be roughly proportional to how much people worry about the world and its future.

The Copernican Principle simply states that the probability of us existing at a unique time in history is small because we are nothing special. We therefore must exist roughly close to half the period of our existence. Using Bayesian statistics and the known growth of population, Gott and others then calculated lower bounds for humanity’s future existence. Referring to the lower bound, their conclusion is that there is a 95% chance that humanity will go extinct in 9120 years.

The Doomsday Argument has sparked a lively debate on the fate of humanity and on different mechanisms by which the end will finally come. As far as I can tell, the argument is little more than inspired numerology and has little to do with any rigorous mathematics. But the psychological aspects of the argument are far more interesting than the mathematical ones; the arguments are interesting because they tell us that many people are thinking about the end of mankind, and that they are doing this because they are fundamentally pessimistic. This should be clear by how many people are now talking about how some combination of nuclear war, climate change and AI will doom us in the near future. I reject such grim prognostications because they are mostly compelled by psychological impressions rather than by any semblance of certainty. Read more »

Two Poems by Muhammed Iqbal (1877-1938)

Bright Rose

You cannot loosen the heart’s knot,

perhaps you have no heart

no share in the turmoil

of this garden where I yearn

but gather no roses.

Of what use is wisdom to me?

Once out of the garden,

you are at peace. I am anxious,

scorched as I search.

Even Jamshed’s empty cup

foretold the future,

may wine never touch my lips,

open circle in a mirror.

Withered Rose

By what words can I deem you

desire of the nightingale’s heart?

The morning breeze was your cradle,

garden a tray of perfumes.

My tears rain like dew,

and in my barren heart your ruin

an emblem of mine.

My life a dream of roses.

Trans-created from the original Urdu by Rafiq Kathwari / @brownpundit.

by Thomas O’Dwyer

![Henri Matisse created many paintings titled 'The Conversation'. This, from 2012, is of the artist with his wife, Amélie. [Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia].](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Matisse_Conversation-360x292.jpg)

“Every visit to California convinces me that the digital revolution is over, by which I mean it is won. Everyone is connected. The New York Times has declared the death of conversation,” Simon Jenkins grumbled in The Guardian, seven years ago. Is it true, and if it is, who cares? That sounds like the start of an interesting discussion. Is daily conversation of any value and if it fades away, who’s to say the time saved can’t be better used? Robert Frost thought that “half the world is people who have something to say and can’t, and the other half who have nothing to say and keep on saying it.” Read more »

Fruit in a bowl in the kitchen of a B&B in Basel, Switzerland, in January of 2017.

by Mary Hrovat

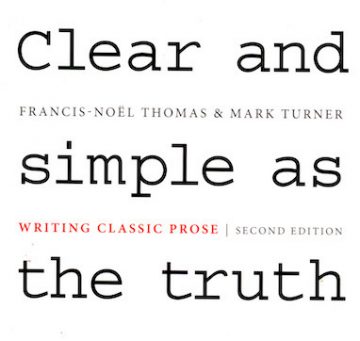

Books about how to write are so frequently described as life-changing and essential (usually by publishers, but sometimes by reviewers) that I was initially unmoved by enthusiastic reviews of Clear and Simple as the Truth: Writing Classic Prose, by Francis-Noël Thomas and Mark Turner. However, the praise seemed to focus on the fact that the book had changed the reviewers’ attitudes toward what writing is and how it works, and that interested me. I decided to get a copy, and I’m glad I did. The book describes and illustrates a particular style of writing but also, and perhaps more importantly, it really did give me a different framework for thinking about what style is and, yes, what writing is. Read more »

Books about how to write are so frequently described as life-changing and essential (usually by publishers, but sometimes by reviewers) that I was initially unmoved by enthusiastic reviews of Clear and Simple as the Truth: Writing Classic Prose, by Francis-Noël Thomas and Mark Turner. However, the praise seemed to focus on the fact that the book had changed the reviewers’ attitudes toward what writing is and how it works, and that interested me. I decided to get a copy, and I’m glad I did. The book describes and illustrates a particular style of writing but also, and perhaps more importantly, it really did give me a different framework for thinking about what style is and, yes, what writing is. Read more »

by Gabrielle C. Durham

Did completing your taxes seem a Herculean task? Did cleaning your adolescent bedroom compare to mucking the Augean stables? Are you more jovial or saturnine by nature? Do you or anyone you know suffer from narcissism? Did you see the movie Titanic? Have you ever been hypnotized? Do you want to go on an odyssey? These questions are all so tantalizing, no?

Did completing your taxes seem a Herculean task? Did cleaning your adolescent bedroom compare to mucking the Augean stables? Are you more jovial or saturnine by nature? Do you or anyone you know suffer from narcissism? Did you see the movie Titanic? Have you ever been hypnotized? Do you want to go on an odyssey? These questions are all so tantalizing, no?

These are not the non sequiturs they may initially seem. Each one refers to Greek or Roman mythology. From echoing valleys to arachnophobia, mythology is a vocabulary geyser for so much of the Western world. Mythology serves us so well for these are the timeless stories of our culture. Depending on how you ethically roll, mythology tends to be more convenient, more easily encapsulated than most forms of organized religion. There’s no grey area with the Greek and Roman gods: Zeus/Jupiter was a tramp, Ares/Mars was a hothead, and Aphrodite/Venus was trouble to any romantic union.

After reading and hearing some of the myths and how they reverberate through literature and entertainment, we grasp some universals of human behavior. The characters and their situations serve as shorthand. Don’t we all understand the admonition not to be arrogant like Icarus and fly too close to the sun with our waxen wings? For those of us who indulge, perhaps overmuch in some bacchanals, we know In vino veritas (In wine there is truth), courtesy of Dionysus/Bacchus. This saying conveys in many languages.

Here are some of the stories behind the terms used in the first paragraph. Read more »

by Emrys Westacott

The relation between what is natural and what is morally good is a topic that has concerned philosophers from ancient times to the present. Those who view the part of a human being that belongs to the material world as sordid, unclean, and irrational have understood morality to require the suppression or the taming of nature; the angel in us must control the beast. This outlook is endorsed by Plato and is commonly found in Christian theology. Hobbes’ social contract theory, which presents moral life and political order as the way we escape the miseries of the state of nature, also takes morality and nature to be in certain respects opposed. Many others, though, have looked to nature for some sort of moral guidance. The Stoics viewed the implacable order observed in the heavens as a model for a serene human life. Defenders of rigid social hierarchies pointed to the successful arrangements in a bee hive. Critics of homosexuality argue that it is “unnatural,” while advocates of gay rights deny this. Appeals to what one finds in nature have bolstered social Darwinism, the subordination of women, arguments for and against slavery, egalitarianism, and the idea of universal human rights.

The relation between what is natural and what is morally good is a topic that has concerned philosophers from ancient times to the present. Those who view the part of a human being that belongs to the material world as sordid, unclean, and irrational have understood morality to require the suppression or the taming of nature; the angel in us must control the beast. This outlook is endorsed by Plato and is commonly found in Christian theology. Hobbes’ social contract theory, which presents moral life and political order as the way we escape the miseries of the state of nature, also takes morality and nature to be in certain respects opposed. Many others, though, have looked to nature for some sort of moral guidance. The Stoics viewed the implacable order observed in the heavens as a model for a serene human life. Defenders of rigid social hierarchies pointed to the successful arrangements in a bee hive. Critics of homosexuality argue that it is “unnatural,” while advocates of gay rights deny this. Appeals to what one finds in nature have bolstered social Darwinism, the subordination of women, arguments for and against slavery, egalitarianism, and the idea of universal human rights.

In Against Nature, Lorraine Daston (Director of Berlin’s Max Planck Institute for the History of Science), poses the following question: “Why do human beings, in many different cultures and epochs, pervasively and persistently, look to nature as a source of norms for human conduct?”[1]The book belongs to the Untimely Meditation series published by MIT Press. At seventy pages, nine of which are taken up by illustrations, and four of which are blank, the book is essentially an 18,000 word essay on this topic.

The modern view of nature that emerged and took hold during the scientific revolution is that it contains no values. In the thought of intellectual pioneers like Descartes and Boyle, the material world is best understood as a vast machine operating predictably according to universal laws of nature. The implications of this outlook for ethics were first noticed by Hume when he observed that there is a logical difference between “is” statements that describe facts, and “ought” statements that express values; moreover, because of this logical difference, it is impossible to fully justify the latter by appealing to the former. Descriptions, by themselves, never logically entail prescriptions. Since then, the “fact-value gap” has haunted much moral philosophy. But even though John Stuart Mill and others have warned against using nature as a moral guide–think preying mantis and sexual relations–according to Daston, “the temptation to extract norms from nature seems to be enduring and irresistible.”[2] Read more »

Sughra Raza. Wabi-sabi. Botswana, 2015.

Digital photograph.