by Tim Sommers

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now?

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now?

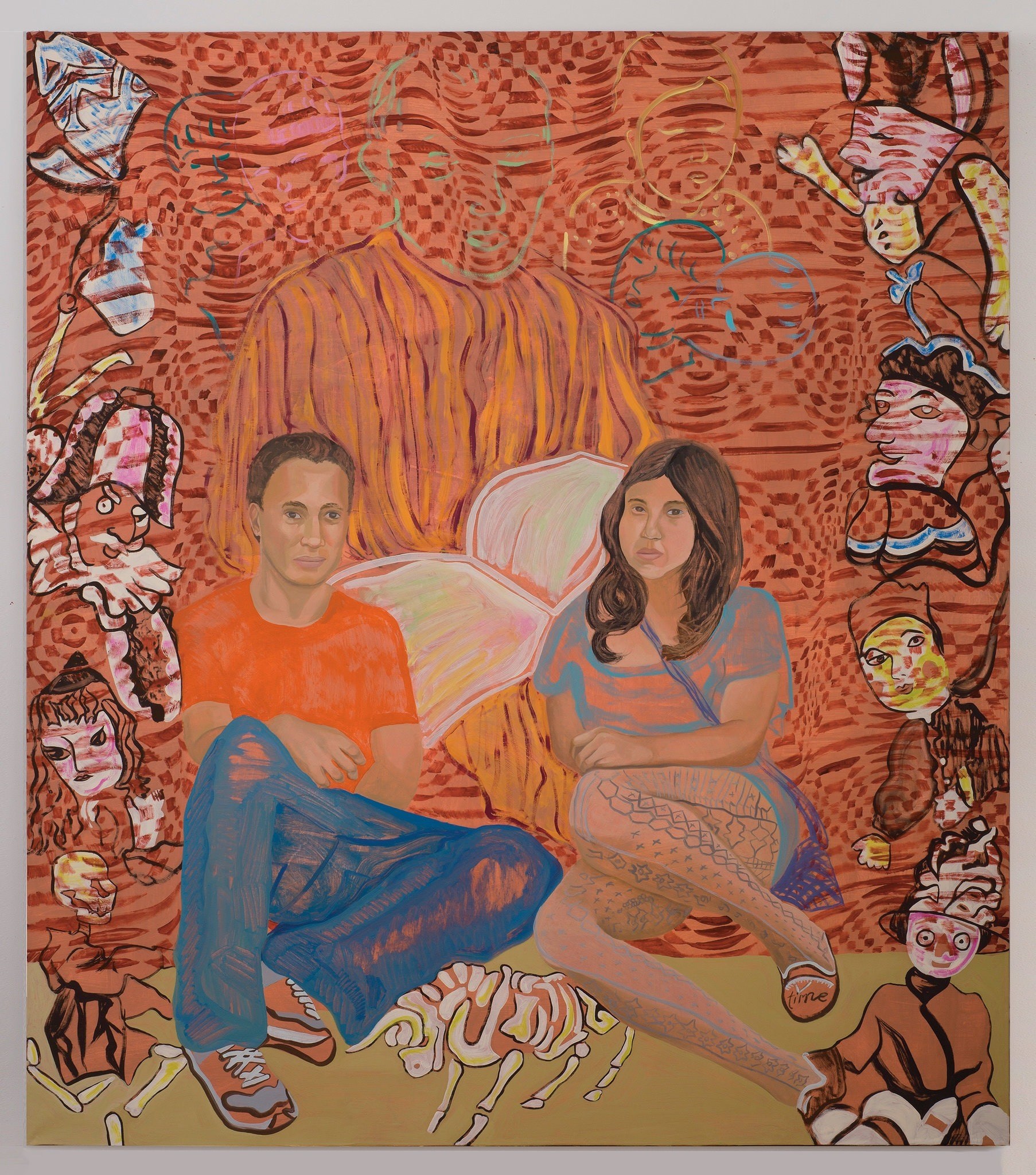

In September, Professor Elizabeth Anderson was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, a so-called “genius grant”, for her work in political philosophy. Though the Foundation specially cited the way she applies her views, pragmatically, to “problems of practical importance and urgency” (most recently with books on race, “The Imperative of Integration”, and work, “Private Government”), the theoretical backbone of her view is a new, original account of social equality – relational or democratic egalitarianism. In a seminal 1999 article, “What is the Point of Equality?”, Anderson asked rhetorically, “If much recent academic work defending equality had been secretly penned by conservatives, could the results be more embarrassing for egalitarians?” Her point was that at the same time that new egalitarian social movements, or at least newly reinvigorated egalitarian movements, focused on race, gender, class, disability, sexual orientation, and gender expression, the dominant form of academic egalitarian political philosophy (“luck egalitarianism”) spent a lot of time arguing about lazy surfers, people “temperamentally gloomy, or incurably bored by inexpensive hobbies”, and those who couldn’t afford the expensive religious ceremonies they wanted to perform. Granted, the characters that inhabit philosophical hypotheticals are bound to be a quirky lot, nonetheless, Anderson wondered what had happened to oppression as the main subject of political philosophy?

Well, here is one way, probably the dominant way in political philosophy, of thinking about equality before Anderson. The notion of equality seems to demand a quantitative comparison. To be equal is to have an equal amount of something. An egalitarian society, then, is one where (certain) things are distributed equally. Call this distributive justice. Read more »

Einstein had called nationalism ‘an infantile disease, the measles of mankind’. Many contemporary cosmopolitan liberals are similarly skeptical, contemptuous or dismissive, as its current epidemic rages all around the world particularly in the form of right-wing extremist or populist movements. While I understand the liberal attitude, I think it’ll be irresponsible of us to let the illiberals meanwhile hijack the idea of nationalism for their nefarious purpose. Nationalism is too passionate and historically explosive an issue to be left to their tender mercies. It is important to fight the virulent forms of the disease with an appropriate antidote and try to vaccinate as many as possible particularly in the younger generations.

Einstein had called nationalism ‘an infantile disease, the measles of mankind’. Many contemporary cosmopolitan liberals are similarly skeptical, contemptuous or dismissive, as its current epidemic rages all around the world particularly in the form of right-wing extremist or populist movements. While I understand the liberal attitude, I think it’ll be irresponsible of us to let the illiberals meanwhile hijack the idea of nationalism for their nefarious purpose. Nationalism is too passionate and historically explosive an issue to be left to their tender mercies. It is important to fight the virulent forms of the disease with an appropriate antidote and try to vaccinate as many as possible particularly in the younger generations.

The roof of Notre-Dame de Paris, lost in the fire of April 15, 2019, was nicknamed The Forest because it used to be one. It contained the wood of around 1300 oaks, which would have covered more than 52 acres. They were felled from 1160 to 1170, when they were likely several hundred years old. It has been estimated that there is no similar stand of oak trees anywhere on the planet today.

The roof of Notre-Dame de Paris, lost in the fire of April 15, 2019, was nicknamed The Forest because it used to be one. It contained the wood of around 1300 oaks, which would have covered more than 52 acres. They were felled from 1160 to 1170, when they were likely several hundred years old. It has been estimated that there is no similar stand of oak trees anywhere on the planet today.

This essay is about technology, probably. I waffle on the theme only because I think blaming existential panic on cell phones is stale, but I’m pretty sure it’s accurate! Let me make my case. I’ve opened Mario Kart Mobile Tour on my phone three times since starting to write this and I’m not yet on my third paragraph. And I’ve already raced all the races and gotten enough stars to pass each cup. And I still keep opening the app. This week it’s Mario Kart, but before that it was Love Island The Game and before that it was Tamagotchi (and Solitaire and Candy Crush and and and). I don’t have a Twitter and I rarely open Instagram so presumably the games are just the most enticing apps I have, but it’s still gross how long I spend with my shoulders tightened, neck tensed, and thumbs exercising. I feel like a loser. And I justify all the time, pretending like I’m having such deep thoughts in the background as I throw red turtle shells. I try to map life onto the racing track; I look for metaphors as I complete a lap and am satisfied with exercising the poetic side of my brain for the day.

This essay is about technology, probably. I waffle on the theme only because I think blaming existential panic on cell phones is stale, but I’m pretty sure it’s accurate! Let me make my case. I’ve opened Mario Kart Mobile Tour on my phone three times since starting to write this and I’m not yet on my third paragraph. And I’ve already raced all the races and gotten enough stars to pass each cup. And I still keep opening the app. This week it’s Mario Kart, but before that it was Love Island The Game and before that it was Tamagotchi (and Solitaire and Candy Crush and and and). I don’t have a Twitter and I rarely open Instagram so presumably the games are just the most enticing apps I have, but it’s still gross how long I spend with my shoulders tightened, neck tensed, and thumbs exercising. I feel like a loser. And I justify all the time, pretending like I’m having such deep thoughts in the background as I throw red turtle shells. I try to map life onto the racing track; I look for metaphors as I complete a lap and am satisfied with exercising the poetic side of my brain for the day.

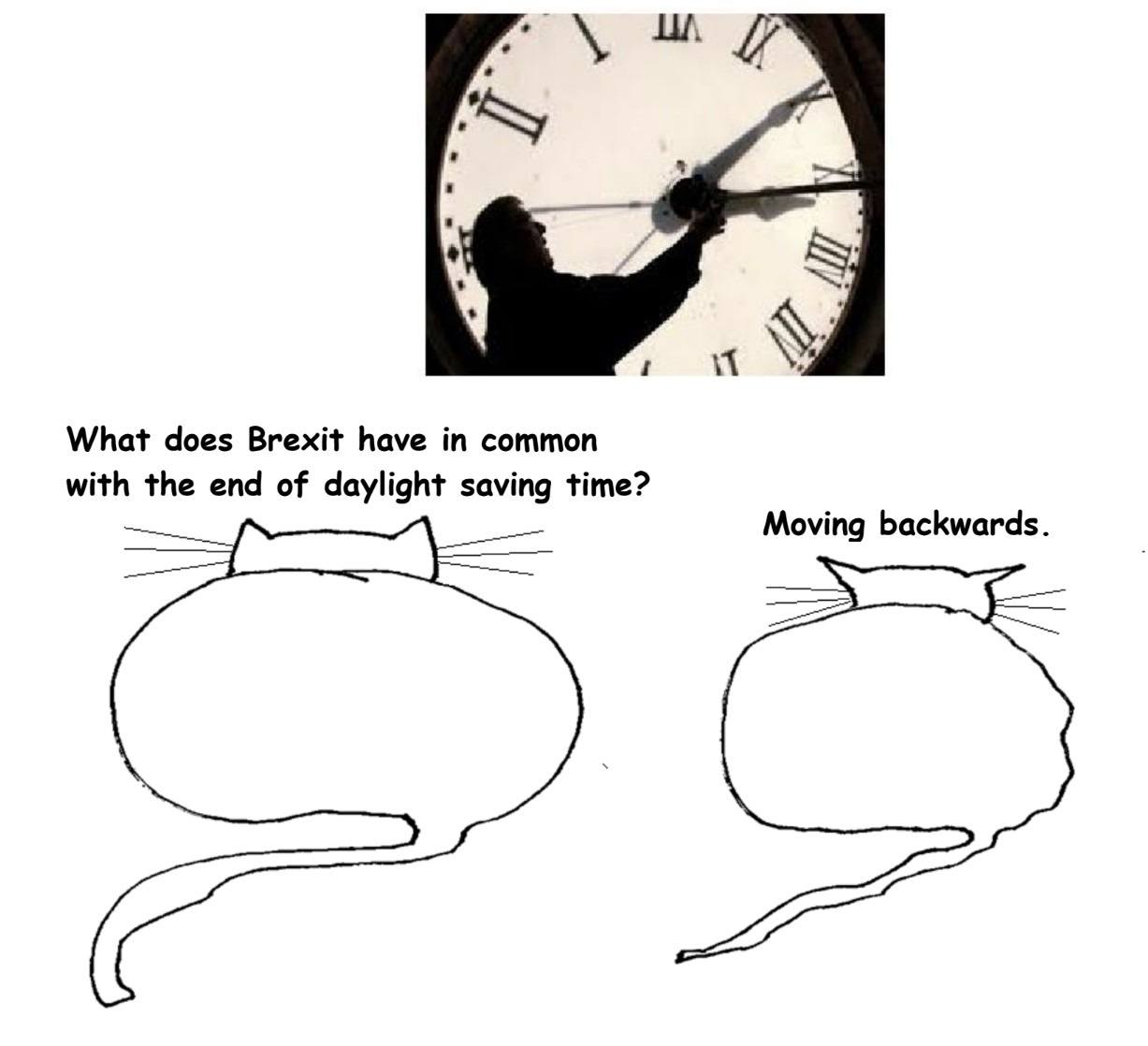

Fantasy politics starts from the expectation that wishes should come true, that the best outcome imaginable is not just possible but overwhelmingly likely. Brexit is classic fantasy politics, premised on the delightful optimism that if the UK were only freed of its shackles it would easily be able to negotiate the best deals imaginable.

Fantasy politics starts from the expectation that wishes should come true, that the best outcome imaginable is not just possible but overwhelmingly likely. Brexit is classic fantasy politics, premised on the delightful optimism that if the UK were only freed of its shackles it would easily be able to negotiate the best deals imaginable. Baseball has always been a thinking person’s game. Like cricket, it seems able to offer an infinite variety of complicated situations demanding subtle analysis, and these are deliciously frozen for everyone to consider and reconsider during the tense, drawn out intervals between moments of active play. Moreover, although afficianados know the rules well, novel problems can always arise. One such puzzler, amusing and thought-provoking, arose in a 2018 game between

Baseball has always been a thinking person’s game. Like cricket, it seems able to offer an infinite variety of complicated situations demanding subtle analysis, and these are deliciously frozen for everyone to consider and reconsider during the tense, drawn out intervals between moments of active play. Moreover, although afficianados know the rules well, novel problems can always arise. One such puzzler, amusing and thought-provoking, arose in a 2018 game between