by Rafaël Newman

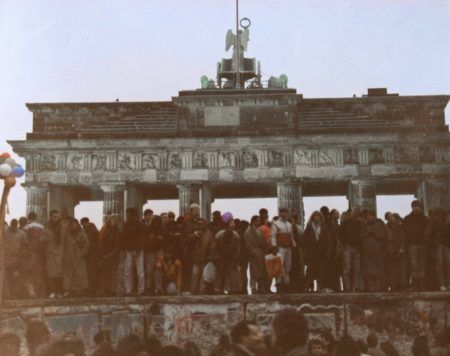

In the spring of 1991 I crossed the German-Polish border at Görlitz and travelled through Zgorzelec, the city’s one-time other half across the river Neisse, into Poland.

The Gulf War had just ended, and the streets of Berlin, where I was spending the year at the Freie Universität, were still littered with cardboard coffins, relics of protest against the US-led intervention in Iraq. A recent visit to the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, to see the Berliner Ensemble perform Brecht’s Die Maßnahme, had been disrupted by activists clambering on stage with a banner that read, “THIS IS WAR: NO MORE EVERYDAY LIFE”, a neatly ironic iteration of the playwright’s own tactic of estrangement as a defense against complacency and the hypocritical respite provided by bourgeois entertainment. Moreover, whispered confabs at the Staatsbibliothek with fellow students at my American grad school also currently abroad were being met with glares of more than usually acid disapproval from locals. So it seemed like a good time to get out of town for a while.

A recently acquired Berlin friend had planned a car trip to Poland to visit family – or rather, the Polish friends who had assisted his German relatives when they were made to leave their “ancestral” home on the Baltic following the Second World War, when that part of Germany was “restored” to Poland, for a new residence on the Rhine – and I invited myself along for part of the ride: from Berlin, by way of Görlitz/Zgorzelec, to Breslau, now Wrocław, where I would part company with my friend before he headed north to Gdynia, his family’s former home. Read more »

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”

“I don’t like Polish people,” he says, and raises an eyebrow suggesting “How could anybody, really?”  are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright

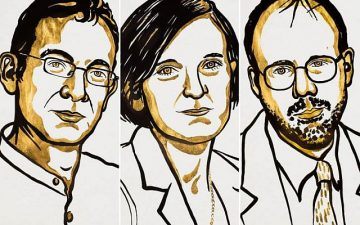

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given.

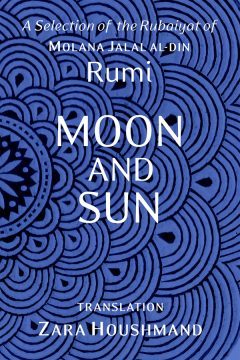

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given. These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya.

These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya. Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the

Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the

One autumn I’m suddenly taller than my mother. The euphoria of wearing her heels and blouses will, for an instant, distract me from the loss of inhabiting the innocence of a child’s body—the hundred scents and stains of tumbling on grass, the anthills and hot powdery breath of brick-walls climbed, the textures of twigs and nodes of branches and wet doll hair and rubber bands, kite paper and tamarind-candy wrappers, the cicada-like sound of pencil sharpeners, the popping of coca cola bottle caps, of cracking pine nuts in the long winter evenings— will blunt and vanish, one by one.

One autumn I’m suddenly taller than my mother. The euphoria of wearing her heels and blouses will, for an instant, distract me from the loss of inhabiting the innocence of a child’s body—the hundred scents and stains of tumbling on grass, the anthills and hot powdery breath of brick-walls climbed, the textures of twigs and nodes of branches and wet doll hair and rubber bands, kite paper and tamarind-candy wrappers, the cicada-like sound of pencil sharpeners, the popping of coca cola bottle caps, of cracking pine nuts in the long winter evenings— will blunt and vanish, one by one.