by Leanne Ogasawara

Earthquake

1.

It was around midnight, Los Angeles time. And my mobile pinged with an incoming message.

“Sorry to text so late, but you should turn on the TV.”

It was from an old friend. He didn’t text me often, so I knew something was wrong.

I grabbed my laptop. There was an email from my husband back in Japan.

“Daijoubu.” It said. I’m OK.

I then logged on to Facebook, where I saw my first images of the earthquake.

By then, almost an hour had passed and communications throughout eastern Japan were overloaded. Working in Tokyo, my husband had no way of knowing when he sent me that first text that the earthquake had occurred over two hundred miles north, off the coast of Sendai.

I wouldn’t hear from him again until the next day.

2.

People will tell you, living in Japan means living with earthquakes. And it’s true. The country accounts for about twenty percent of the world’s earthquakes of magnitude six or greater. Being from Los Angeles, I am no stranger to earthquakes. But in Japan, tremors are a weekly occurrence. Over the years, I had grown used to their frequency and had learned to hear them coming in the rattling of windows, which I always sensed before the shaking started.

Shhh!… jishin desu! (Shhh!, I hear an earthquake!)

Friends talked about earthquakes like they talked about the weather. It was a way of making small talk. So was telling each other about recent purchases of disaster supplies. We all kept stockpiles. Like most Japanese people I know, despite always being prepared for the worst, my husband was always blasé about earthquakes when they happened.

But this time was different.

3.

When we finally connected by phone the next day, he told me what he experienced.

Working on the 12th floor of a large modern office building in Kawasaki, he hadn’t even bothered to get up from his desk to take cover the first full minute of shaking. But, he said, it didn’t stop. Instead, to his growing alarm, the shaking grew stronger.

“It seemed to go on forever,” he said.

Everyone in his office had been stunned by its duration.

They had no way of knowing this at the time, but in the north near the epicenter, the earth had convulsed for some six minutes.

As soon as it subsided, everyone was instructed to evacuate the building. By then, someone had gotten the news that the epicenter was in Tohoku. Given how violent the shaking was in faraway Tokyo, he told me, everyone realized that this was a disaster.

The tsunami had still not struck. That would happen less than an hour later and almost two hours before news of it reached Tokyo.

Expecting aftershocks, authorities halted most of the trains and subways. This meant my husband had to walk home. Well, not home, but rather to a company apartment in Kawasaki. It would take him several days before he could make it back to our home in Tochigi—halfway closer to the disaster zone.

After traipsing down ten flights of stairs, he was handed a white helmet and some food from company staff. Large corporations in Japan kept emergency supplies for just such a situation. It took him several hours to make his way on foot across the city from Kawasaki to Yokohama.

“There were crowds of people silently walking through the city. Everyone looked to be in deep shock,” he said.

4.

One of the most famous works of literature from the middle ages in Japan was Kamo-no-Chomei’s Hojoki.

Like I said, Japan is no stranger to earthquakes, and in the early 13th century Chomei described watching as the capital of Kyoto was rocked by a mega-quake that “toppled mountains and filled the rivers.” Horrified by the suffering and anguish of this broken world, he left the capital to live a life of contemplation in the mountains. And there, in his ten square foot hut, he realized that everything in the world comes down to mind.

The current of the flowing river does not cease, and yet the water is not the same water as before. The foam that floats on stagnant pools, now vanishing, now forming, never stays the same for long. So, too, it is with the people and dwellings of the world.

I went to bed that night in Los Angeles thinking of Hojoki’s sad lament– Having no idea, not even a premonition, of the coming disasters.

Tsunami

5.

By the time I woke up the next morning, the news was being reported that the 9.1-magnitude mega-quake that had hit Japan was one of the largest earthquakes on record. It would shift the landmass of Honshu Island almost eight feet closer to the United States. The earthquake, centered off the coast, raised a deadly wall of water 250 miles long, travelling around 400 miles per hour toward the Sendai coast.

The footage on TV was otherworldly. Less a gigantic wave, what people faced was relentless rushing water. So powerful, it dragged everything under in its path. Ripping the clothes right off people’s bodies, it destroyed buildings down to their foundations. It was like an angry dragon destroying and devouring. Later, experts compared the aftermath of the tsunami to Hiroshima in the wake of the nuclear bomb. Entire families were wiped out. Watching, the indescribable human suffering, I couldn’t help but feel the dead were luckier than the survivors; for how to go on after losing husband and children, parents and siblings?

It was still too early to grasp the number of dead and missing. Japanese newscasters on NHK were suggesting figures of around 6,000 dead with countless missing.

By the end of the year, the estimated number of dead would rise to 20,000.

6.

Another worrying development that first morning, Los Angeles time, was the suspected partial meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi Unit 1 nuclear reactor. This had occurred when the tsunami washed away the emergency generators necessary to run the cooling water pumps and all reactor safety systems. Hydrogen explosions had been reported releasing contaminated radioactive gas in the nearby area. Like many people watching the news coverage, I could not believe my eyes. Our house in Tochigi was less than 150 miles from the reactor. Which way was the wind blowing? How much radiation had been released?

7.

That evening after dinner, while my son was in the other room watching cartoons, my mom whispered: “I can’t believe our luck. Can you imagine how worried I would have been if my daughter and grandson were there now? Given everything, you can just stay awhile, as you think about things…”

She didn’t finish her thought. But she was well-aware that this trip home to Los Angeles had been different than previous visits.

For one thing, I had come on a one-way ticket.

While I had not consciously planned to separate from my husband of twenty years, I had traveled back to Los Angeles exhausted. That year before the earthquake, I was in my second year working as a translator on several telecommunications white papers and ministers’ speeches for the Japanese government on their eJapan policy. The Kantei (Office of the Prime Minister and his cabinet) had established its program to turn Japan into an advanced information and telecommunications society. By the time I became involved, the strategy was in full swing.

Working for the Cabinet Office was stressful. Every word in my translation was scrutinized. When they translated my English version back into Japanese, nothing could be missing or ambiguous. The work was tedious and involved endless back and forth with Ministry staff members.

I was alone constantly, and between working, taking care of the house, child-rearing and the endless school and neighborhood obligations that are part of life in Japan, my days took on a blinding busyness. And before I knew it, I had become physically and emotionally worn down. And more than anything, I had grown tired of being alone all the time. My husband and I had grown apart.

So, while I was not consciously planning to leave Japan forever, I had booked a one-way ticket. And at the last minute before my flight, I had thrown in a few of my treasured belongings. My choice was haphazard— a small bag of jewelry, a Yixing teapot from Hong Kong I adored, a little basket I had bought years ago when we lived in southern Africa. I tossed these sentimental belongings into my suitcase along with some clothes and toys for my son and left.

Meltdowns

8.

My husband encouraged me to stay with our son in Los Angeles with my mom until we could figure out exactly how much radiation had been released and how our home had been affected. For weeks, Tokyo had rolling blackouts, and at first it was not clear whether there might have to be an evacuation of the entire city.

But how do you evacuate 10 million people?

It would take several weeks before the meltdowns were under some kind of control and the government grasped the level of radiation exposure.

Those were terrifying days. Depending on winds and weather patterns, radiation hotspots would develop far from the power plants while places closer were relatively safe. No one knew what to feed their children and friends told me that it felt very dark even in Tokyo, as if the nation had lost heart.

The US government issued a travel advisory and people there were urged to leave. Some Japanese felt the foreigners were like rats leaving a sinking ship. They even had a name for them: “Flyjin” (A play on the term flyaway gaijin, or foreigner.)

9.

9.

In the months that followed, we watched as the three reactors failed. Three meltdowns and multiple explosions… each day brought new heartaches. For weeks, I was unable to move away from the TV. And what I saw were scenes of hell-like devastation.

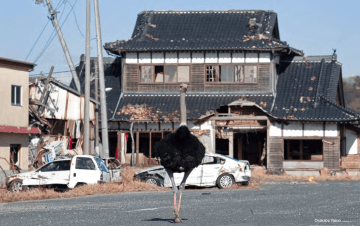

Buildings that looked bombed out, black slimy seaweed covered everything after the waters retreated. There were cars abandoned in fields and large boats left aground miles inland from the sea, empty houses without windows, and abandoned dogs roaming the streets.

In the nuclear evacuation zone, so many animals— cows, horses, dogs and cats and chickens, pigs, and even ostriches—were abandoned as people fled just a step ahead of radiation exposure.

10.

One story above all stands out. There was an elementary school in Miyagi Prefecture that later became known as the “school beneath the waves,” because the entire school had been wiped out. So many children lost— many whose bodies were never recovered.

The parents couldn’t rest.

There was a mother who was interviewed on Japanese TV. Waking at dawn every morning, she spent her days on a rented digger shoveling the debris for any sign of her daughter.

She knows her child is dead, but her need to care for the remains is overwhelming.

What if her daughter is made to wander forever, a lonely ghost? How can she visit her daughter if there is no final resting place? Will her daughter’s soul ever be at peace?

She tells the interviewer about the time she uncovered the body-less head of another child in the debris. One of her daughter’s classmates. She said, “She must have traveled so far in the water… This was all that was left, but maybe her parents can now rest.”

11.

11.

During these first several months after the earthquake, I felt everything break. My marriage, my life in Japan, my connection to my closest friends, my sense of well-being. Everything. I was so lucky to have missed the disaster, but from a safe distance I was watching a house of cards collapsing in slow motion, as twenty-five years of my life fell apart.

The best book I’ve read about the disaster in Japan was Richard Lloyd Parry’s Ghosts of the Tsunami.

“A tsunami does to human connectedness the same thing that it does to roads, bridges, and homes,” he writes. “And in Okawa, and everywhere in the tsunami zone, people fell to quarreling and reproaches, and felt the bitterness of injustice and envy and fell out of love.”

I know husband felt the same. We both became so brittle. I wish the disasters had brought us closer. But we were like a vase with a thousand cracks in it, when the earthquake pushed us flying off the shelf. He would eventually fall sick a few years later— probably from stress.

We were divorced by then.

12.

Fukushima was the world’s second-worst nuclear accident, after Chernobyl. The world watched amazed at the orderly and disciplined behavior of the Japanese during the first weeks of the crisis. We saw extraordinary acts of self-sacrifice by employees of the reactors, as well as residents displaying composure and patience –and yes, the most quintessentially Japanese concept of gaman(我慢or grit) during months of hardship in evacuation centers. I read article after article suggesting that what we were seeing in Japan was the best humanity has to offer.

Almost two years after the disaster, I spent several months working on translations of several papers for two professors of psychology at a university in Tokyo working on the topic of post-traumatic growth. Like Post-traumatic stress disorder, post-traumatic growth is a reaction to a serious traumatic experience, but in this case the reaction can be viewed in positive terms.

At the time, it seemed wrong-headed. So many had died, with countless survivors struggling with anxiety and depression, and waves of suicide. Hadn’t the disaster struck the death blow to my own marriage and life?

I almost didn’t take the job, as it felt too close to home.

For the project, 161 essays written by school-aged children, who had undergone serious trauma during the triple disasters, were analyzed to try and explore the possibilities for personal growth.

The young people, each who had experienced trauma– including death of a loved one or several loved ones, serious injuries, loss of home or even all of the above– were discovered to have written about what the professors described as “spiritual growth” (I might have mistranslated that actually, I now see). The positive growth included a deepening appreciation of human relations and strength in human bonds, an awakened sense of wonder, secular to some, religious to others, about nature and the world. The young people expressed a strong resolve to live on, despite the tragedy, to honor those who had died.

I translated many of the original essays–and they were extraordinary.

Parry, in his Ghosts of the Tsunami, had uncovered very similar types of human growth experiences in the survivors. People recounted to a priest how, in the midst of the terror and darkness, they were stunned to look up and see the splendor of the night sky, visible for the first time.

They spoke of seeing dead bodies washed up on the beach and yet inexplicably feeling the boundaries between the dead and themselves disappear. This was, the priest told Perry, the enactment of jita funi (自他不二), literally “self and other undivided.”

Broken ground, broken lives, broken dreams

13.

I worry that this brokenness will always be part of me. While my son has returned once, and his father has visited us here, I have not been back to Japan.

Chomei says that,

Reality depends upon your mind alone. If your mind is not at peace, what use are riches? The grandest halls will never satisfy.

I love my lonely dwelling. This one room hut…

Japanese Buddhist literature is filled with this struggle to overcome the pain of transience, a fact that is intrinsic to our lives. There is no escape, as we all know, for bad luck is an equal-opportunity act.

14.

Hard to believe it’s been nine years.

My thoughts of the disaster always bring me back to Voltaire’s Candide. Especially, I think of the novel’s opening chapters, when the luck-less Candide– along with the syphilitic Pangloss and the sailor from the boat– were shipwrecked; washing up on Lisbon’s shores just moments before the city was struck by the infamous mega-quake of 1755.

A pre-echo of 3-11 Japan, as if the mega-earthquake wasn’t enough, it was followed by deadly fires and a giant tsunami that destroyed one of the world’s greatest cities. The human suffering was so terrible that the disaster sparked philosophical and religious debates on the nature of Evil that continued across Europe for decades. How could an all-powerful and benevolent God allow so much suffering?

In the wake of the disaster, as Candide is lying trapped under the rubble, he begs for wine and light. The sailor has gone off to pillage– but what of Candide’s companion Pangloss? Well, our man Pangloss is too busy philosophizing to be of any real help. Though thousands have perished, he tells his friend still lying under the broken buildings, that everything is just as it should have been, for: “How could Leibnitz have been wrong?”

How indeed?

++

To Read:

Hojoki, by Kamo-no-Chomei, translated by Yasuhiko Moriguchi and David Jenkins

Alison Watts’ beautifully written essay in Words Without Boarders:

Literary Journeys: Living Through Art in the Wake of Disaster

Ghosts of the Tsunami, by Richard Lloyd Perry

To Watch:

Footage of Sendai Airport During Earthquake and Tsunami

To Think About:

Lucy Jones at Caltech has repeatedly warned us to prepare for the big one in California. She thinks, and I agree, that our connections and ability to work with our neighbors is one of the single highest determiners of survival. The Japanese worked together in a way unthinkable in Los Angeles. She has been urging people to form neighborhood preparedness groups. My friend Beatrice told me about this. She is a leader for such a group in Santa Monica.

Animals

Science Alert: Animals are Flourishing in Fukushima Exclusion Zone

Fukushima Pictures in the Guardian

++

My Notes Here

If you have a suggestion for books to read, I am all ears.

If you were there, I would love to hear your thoughts.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mk68bZ701s0&feature=emb_title