by Thomas O’Dwyer

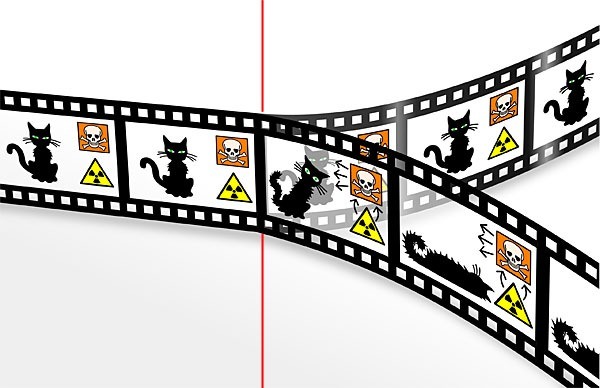

Our world (made of atoms) is crammed with paradoxes. Particles act like waves, waves like particles And your cat can be dead and alive at the same time. Just step through your looking glass and welcome to the quantum world. “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you haven’t understood quantum mechanics,” the physicist Richard Feynman once said. Of course, the non-scientific reader may respond, “Why would I want to understand it?” If a genius like Feynman became lost in the twisting labyrinth of the quantum world, abandon hope all ye who expect to become enlightened here.

Quantum theory is famously opaque, and it drew dismissive grumbles from Albert Einstein. He was one of many superior minds who worried that science was abandoning its high road of rigorous clarity to dabble again in the murkiness of faith and superstition by even pondering the notion of quantum reality. Alive-dead animals, parallel universes, the existence of all times past present and future? These were for April 1 spoofs, right guys? Yet, whether one is aware of it or not, quantum mechanics has given us lasers, smartphones and many esoteric electronic components, like tunnelling diodes, from which we build our devices. They come with a weird label that says, we made them, and they work, but we don’t quite know how. Quantum computers will soon solve problems well beyond the reach of present-day digital machines – complex chemical analyses, dynamic biological processes. These will be of use to the pharmaceutical industries, and they will also model complex systems like financial transactions and climate changes. Read more »

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose. Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

by Paul Braterman

by Paul Braterman

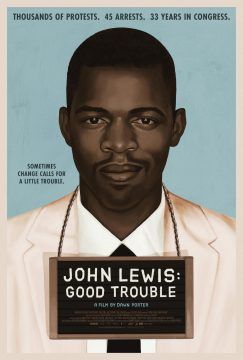

John Lewis: Good Trouble

John Lewis: Good Trouble

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time.

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time. Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.