by Eric Miller

1.

A robin in the floating height of a pine warbled its fat phrases of three and, with its chest matching the tint of twilight clouds and light on leaves and houses—a lucent, resinous colour such as collected at the lower tip of every cone—, it seemed at once the motivation and the record of the fall of night.

Cartwheeling girls were to be expected. I knew, as one of the few boys in the neighbourhood, girls are more athletic than boys. They spun across the thick grass, not all grass, not meticulously kept; they spun beneath the widow’s white pine, she did not mind all the kids on her grass or depending like apes from her tree. A scent of crushed stems (in equal parts acrid and balmy), the clover-like odour of sweat in hair, made the affinity of plants and us amenable of olfactory proof.

The hill behind the widow’s house, pressing a slow muzzle to its foundation, distorted the building’s shape amiably—amiably, that is, to outward inspection. There must have been interior cracks and derangements. I have no evidence. I never went into it, only looking at it from the porch, or aslant from a higher elevation than the wrested roof. The widow had red hair, redder at dusk.

One girl especially was a virtuoso of jumping rope. She sang out the lyric that helped coordinate her steps; she might have been a sword-dancer, she was so agile; I listened for how her confident rendition of the rhyme became intermitted with gasps as, her pace not slacking, her smile brightening while she held it, her eyes contemptuous of any downward glance, her exertion made her fetch air harder into her lungs. The lyric went, Or-di-na-ry sec-re-ta-ry. Here was nothing ordinary, I would be happy to be its secretary: which has the word “secret” bosomed in it. Besides, I knew that secretaries were among the kindest people in the world.

These local girls—there were many of them—might have adorned a Minoan mural. They performed their feats from no motive but rivalry among themselves and pleasure. They imparted pleasure, I can retrieve it still. I stood so close the air they disturbed struck me, not a shock wave but a wave of intimacy. I was often frightened—I am still frightened—by how low the buffer is between our lives and the empty reach of sky, of blue outer space and black outer space. Absence of air stops our pulmonary lives, we are stuck pretty much on the ground unless we submit to awful, precarious rigmarole and precautions. Trees seemed too short, towers too short, clouds both too far away and still too close.

A girl revolving year-like past (an ecstatic human wheel) fixated my attention. She countered my fear of our crawling smallness. She offered, as an antidote, her bony brutality—brutality of confidence, of pride—to magic away an apprehension of our entrapment even at the moment that promises us our liberty (a remedy offered, alternatively, by the wrinkles of a tree’s trunk, pre-settlement possibly, or by the view of a bird, beak tilted up while brooding on a nest in which it invested, the cup no bigger than a breakfast bowl, the perpetuation of its bold, frail kind). A girl’s grass-dyed knee, biotite mica in a pink rock: these knobby proximities protected me in the benevolence of their approachable plenitude. I was always in search of a way to escape the day yet to embrace it.

The vitality of others in itself presented a problem. Inexhaustible in appearance (these rolling and cavorting girls), the scene exhausted me when I considered trying to entertain it, trying to court and to detain it. As a spectacle, it refreshed me; as a transitory turbulence at the conclusion of which I would have to sustain conversation, it afflicted me with tiredness and inability. Slick, bumpy, laughing, gleaming, even bleeding touch I could imagine, and in fact I put myself in the way of it, its roughness answered to my ignorant desire. Anything less tactile, less animal, anything involving the faculty of cogent reciprocal speech, scared me and (I confess) in some measure it still does. Meanwhile amid shouts more delightful for their timbre than for their wit, night did not fall but well. By bringing outer space to earth, it relieved me.

Every advancing minute modifies sound. Shrieks enriched by a vibrant giggling reverberated: mead or ambrosia, slopping in a jug. Have you never understood that night is thoughts and you are allowed to draw from them and there is no end to them? The painter was passing, returning from her walk. Her smallness came attended by an aura of bravery, as though she strolled through the falling pumice of a Vesuvian eruption, sending what presumed to disaster us back to its source. Pliny as Prospero! She was conscious of our respect as she went past, a well-put-together, an allegorical figure, not a parent: a historical personage, her own history painting as a matter of fact, cousin in this respect to the lean mathematician across the road who pondered, within the compass of a simple circle, infinitude—which (he tried to explain) was both crowded and empty. The painter’s hat hardly possessed a brim yet we took cover beneath it. This rounded hat—both an exuberant bubble just dilated and the durable dome of a dependable landmark—seemed altogether a helmet such as would preserve not only her from the onslaught, but us too, a fancy supported by the fact that, young as we were, some of us already overtopped her considerably. How often a diminutiveness has outlasted titanisms of all kinds.

2.

Years later, the painter had the patience to look at my paintings—always out of doors where I brought them to her, regardless of the season, snow flaking like old starlight from the cloud ceiling or a wilting mugginess shellacking me in runny enervation, making my lips feel puffy and slack.

She wanted to handle these pictures, grasping them physically was a part of her judgement. She held the image I passed to her, tilting it like a ship’s wheel with a measure of incredulity. She had the air of one who had to keep a grip, or a gust or a wave would tear my offering away in a flash. She always said “Too commercial!” Still she palliated this damnation by admitting the saliency of some colour or detail. It often struck me that the colour she praised was a thing anyone could supply. The tube of paint was responsible, or (at most) the minimal, condiment-squeezing competency to mingle a couple of pigments: horseradish and relish, let us suppose. As for the detail she singled out, sometimes I understood her emphasis. But frequently the opacity of the grounds for her approval indented a cleft of hard puzzlement in my brow like the crease a little mishap imparts to sketch-paper, maybe vitiating the work, maybe by chance improving it.

“Too commercial!” The verdict rang out at the foot of our stone stairs and the foot of hers. A footpath united our stairs at the top, but she never took that shortcut. One picture thus inspected sticks in my remembrance, randomly more permanent than the rest. It was the fall. I had painted a dead male dignitary laid out for viewing. An open coffin. For me the point was, I think, yellow and isosceles triangles—not without a varnish of youthful morbidity, of ambiguous scorn (or respect) for the socially great. I had chosen for my canvas not canvas but a wooden board I had salvaged with a rough surface. I trawled through the world in those days, looking for scraps. Even a waste lot with its sere tansies and stinging bugloss might have opened a cleft into the forgotten lavishness of ages long preceding the first invention of what, by our time, was reckoned extinct for good. Ur-phenomena. The eldest yet youngest of forms. Everything was a still life, everything was the same age. My job was to gather it, I was a harvester. In neglected places full of discards, time was simultaneity of times.

“Too commercial!”

Sometimes we have been mounting the steps for decades before l’esprit d’escalier gets a word in. I never rejoined: I could not have sold such a thing had I tried my hardest. In those years I kept trying to wedge myself into what Toronto offered, and what Toronto offered was at variance with what I could do or wanted to. Even my efforts at compromise with the prevalent manner, with prevalent expectations, came off as ridicule or pitiful barbarity, a misfit that (once I was dismissed again) brought me the Hadean savour of confirmed solipsism, the shudder of being hammered on the mind’s funny bone. I could glimpse that to conform takes as much energy—even talent—as to refrain from that imponderable accommodation. I lacked the competence to be fashionable. I could not read the standard time. It is a mode of prophecy, albeit one alien to me, to be consumed and approved by the avid moment as it flies. Arbiters marked the bounds of their visible outworks with eroticized puffery and further evidences of solidarity, handbills (for example) testifying to it and sundry propaganda—ephemera, had I understood the truth at the time. I gawped, I slouched and I paced, baulked as before the rampart of a colonial fort designed, with a local crudity, after the far pattern of the starry Marquis de Vauban, from whose witty designs everything uninvited so charmingly bounces. As for them—the garrison—they had a talent for friendship but often this was their chief gift. They never opened the gate. All the same, the fort has mouldered away.

3.

When I was still small, perhaps in grade one, the painter came into our backyard and fixing me with her eyes, her hands on her hips, her cloche hat tilted on her head, she vituperated the fate that condemned women to menstruation. She was the first person from whom I received a comprehensive account of the topic. I had seen my mother’s bloodstained sheets, I had seen tampons; but the painter, with exuberance, comedy and anger, conveyed the nuances and consequences of this monthly cycle to me, with all its concomitants as she understood them, and rebuked me for being male and exempt from this particular destiny. Yet she made that destiny sound worthwhile, because of the rhetorical opportunities it offered and because of the implicit contribution it made to her extraordinary vivacity. She made me love her in several ways; one of them undoubtedly consisted in her being not just female, but articulately so.

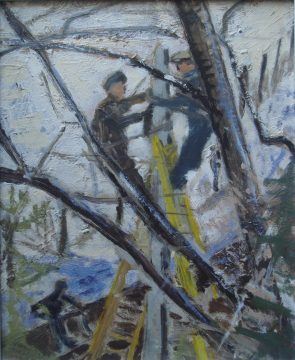

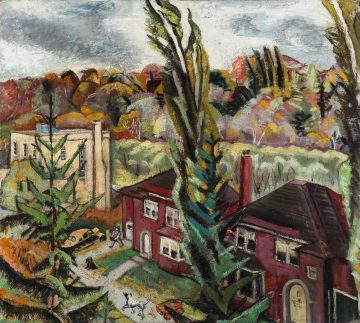

Her god was Cézanne. Je vois par taches! “My vision comprises patches only.” True also of the genius of the hill-slope where we lived. For it expressed itself seasonally in leaves themselves naturally in conformity with Cézanne’s saying. A Cézanne is now frankly flat and linear, a plane that will not abnegate allegiance to its original two dimensions: yet now it hosts, it prospers a local, a strong, even an intrusive passage of modelling: just the practice favoured by exfoliated plants, especially as they stagger themselves in their array, stacking boughs, inter-penetrating sprays, populating an incline in Toronto. Paraskeva Clark cherished trees. In her paintings, plumicorn owls and ladder-propped linesmen live equally at home amid branches. They belong to the same genus: the Cézanno-dendral.

Another topic with her was Stalingrad. Every theme she took up possessed her bodily, she might have been the Delphic priestess, her spare person became dense more than frantic as it acceded to the spirits of rhetoric and her kind of clairvoyance. I had (it was only reasonable) a horrible image of this battle, cold, remote, starved, protracted and was glad that the painter left the subject behind for other things when she did. The painter effectively sculpted the drifts of our winter, which back then in their blockade passed for sufficiently Soviet, into tumuli of blanched bodies, frosted guns, armour of ice conserving death more than reserving any remaining life. Her family had endured the siege of Leningrad, yet she was more persuasive when she addressed the other city. Then, leaving Mars behind, she would express an exasperated love of Picasso. The basis of both the exasperation and the love was his sex. The thing that attracted her but that also comprised the failing of his art was his masculinity. War clenched Paraskeva’s great hands; Picasso relaxed them.

4.

When does evening end? My father and I often sat late and kept calling the deep night the evening, by this misnomer protracting the pleasing illusion that we could stay up forever without consequence. I had (at least in years) attained young manhood. My father said, “All the wives of our neighbourhood forbade Paraskeva to attend the funerals of their husbands.” Silence followed the declaration, which he made only once. After a time he said, “It’s funny” but he did not mean it was droll or comical.

I knew by then that many women might be forbidden to visit certain husbands’ funerals and that those women had painted nothing. People like to grab hold of something common in order to wrest the uncommon back into place, or rather into a place it never was but it should be. It is always important to avoid looking at the art, and to scrutinize the frowns of the wives. Now we wear that frown too, vindicators of persons whom we never knew.

Meanwhile in other ways we do worse, true not a matter of husbands, true not a matter of wives; huffing, nose to ground, morality tracks certain derelictions with the most exemplary fidelity, but stifles others before they can confess. Throttle them as we may, they will confess!—if we are obliged to be moral, then we must refresh our scope. It all lies within the compass of the simple, inescapable circle. Otherwise, give it up. We like to think of people having sex, we like it by itself and then we like to judge it. The judging is a part of the sex no doubt about it. Why do we vindicate strangers? (The customary method is, we do not ask them beforehand whether they want to be justified by us or not.) We vindicate our pleasure in sex by disapproving of it.

“You should not have done that” is the watchword of our own way of doing what should not be done. What a delightful contortion! A pose worthy of Pietro Aretino. We might adopt the savoury shape of the famous snake the ourobouros, our own tingling tail between our lips, spat out now and again, mind you, or meatily mumbled past (so gripping-hot careers the torrent of gossip, in spate forcing us from ourselves at intervals before we can resume the dear circuit). We like our vindication best when we have not gotten the prior consent of the ones we vindicate, so we can have sex in all kinds of ways—if sex is to be understood in this fashion. Who fucks who, as the ethical giant Rochester once put the case. Goodness, that feels good. Let me tell you.

Can you renounce the vindicator’s heady, venereal delight? To rescue and to punish are infinitives as intimate with each other as partners to intercourse. I have done my share of attempted vindication (years of it). But I made bloody well sure first that it was what the one “vindicated” wanted. The choice to seek consent in this way was (I have to allow) pragmatic in tendency. After all, once you start where do you stop? It has to be personal, that is my sense: most times. The lawyers alone! My counsel? Look to your own genitals, reader, and be honest.

Mrs. Clark climbed out of her day, whatever it was, and into pictures of her own. The husbands and the wives, whether smiles wreath or scowls contract their visages, should not (in this connection) be reproached unduly: or celebrated, either. Her pictures were on our walls—she was our neighbour—and I confronted them over and over again. They sibbed me as surely as sister or brother. They had (they have) something in them. It is different from titilla-, I mean to say “vindication.” You know, not the rush of blood to the righteous part. Also, sex is not usually the painter’s topic. Yet every one of her works, almost, is as interesting as sex.

5.

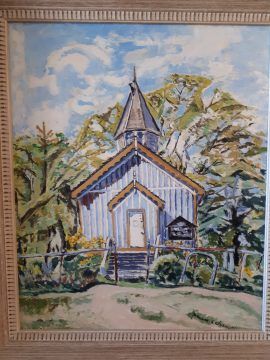

For example, Mrs. Clark painted a church. I do not mean she stood on a stepladder with a broad brush, and she renewed the coat on such a building. No, she made a picture. A common topic for Canadian painters at the time, a little church. A tin roof in Québec, cedar shingles on a mossy shore of the Salish Sea. To Mrs. Clark’s Ontarian spire clings a woodpecker.

A woodpecker’s feet are organized somewhat differently from a songbird’s. The toes appear in pairs, the second and third toes in front, the fourth and the hallux behind. This arrangement, helpful for arboreal and perpendicular life, is called “zygodactyl,” a term that suggests an unusual metre. And woodpeckers are adept with metre, the drumming of their beaks against a surface announces—annexes—territory. When I look at Mrs. Clark’s bird, I identify it provisionally as a Hairy Woodpecker. It may be (all right) a flicker or a Pileated Woodpecker, but if it is the former the painter has exaggerated its angularity; and if it is the latter, it has depressed its vivid crest to flat invisibility. The size suggests a Pileated, really. I like the ambiguity.

This woodpecker faces right. Anyone who watches these birds knows that they swivel on an upright support, spiralling with something of a jagged habit of motion. The difficulties in the matter of putting a name to the species derive from the fact that, unlike most things in the painting, the woodpecker appears in perfect side-face silhouette. The church stands, it would seem, embowered by forest.

Mrs. Clark, who professed communism, also professed to dislike the church. This abhorrence was comprehensive. “The church,” considered thus collectively, comprises a great many buildings. She did not dislike the buildings, this one appealed to her. It appealed likewise to the woodpecker. She might be that bird.

The woodpecker reconnoitres the church spire as an aspect of its domain. Not a bell ringing to summon a rustic congregation, instead the bravado of a small, savage, stylized bird. What does not please in the conception of a woodpecker? Its attitudes, abrupt yet ceremonious, break off each from its predecessor as distinctly as fragments bursting from under its stroke. Its undulation from trunk to trunk has the weight of a swung hatchet, wings drawn in beat by beat with the severity of repressed gasps. Its cry splits quiet as sharp as a pick. Its private crooning disposes tenderly of its otherwise prevalent aura of ligneous inflexibility. We hear its scratchy, zigzag feint round the bole, it peeks, it glares as the bird finds a curved vantage past which to stare at us. Its excavations and its drillings, its worksites solace in the waste. Here was purpose however long ago, desolation leaves me now (thinks the wanderer) though I lack a human friend. Thus the bird, like the thoughtful provider of a cache or the heaper of a cairn, supplies the avian counterpart to bear-sign. I mean the overturned stone, which bespeaks life.

How little really can establish a path or a sex the woodpecker demonstrates too. The male with his fresh-painted, always wet-painted patch of red on his nape reminds us of a blaze made by the side of a trail. As that blaze alone assures the existence of the trail, so this vermilion dab on the hind-neck precariously stabilizes our claim, “He’s male.” Consider now the Hairy Woodpecker’s monochrome plumage—camouflage quite ostentatious (if we may be oxymoronic). Consider its eggs that can afford to be blazingly white, for they are reposited in the blackness of a cavity. I am historical, I can recall when Red-headed Woodpeckers still bred in the Don Valley. I have held sapsuckers in my hand and they have whined and squealed, quite without any of the submissiveness that these verbs import in our impoverished English language. Love live woodpeckers! Long live Mrs. Clark!

The bird may inflict its characteristic though slight damage upon the church steeple, unless its blows hit metal sheathing, a resonator for its proclamation. The truth is there is no church for the woodpecker. Mrs. Clark gives us to know everything we have made and everything we do and have done is ceded at once to other worlds. There, there is no socialism or Christianity or art of painting, but nothing sees the same thing and were there only one thing to see that would (even so) be enough and more than enough. Nature collectivizes by individuating. Mrs. Clark’s woodpecker has displaced politics and theology. It raps out (the irrefutable poltergeist!), “Your interpretation is never total, is far from total, it misses the mark it seems to hit. In fact your dearest possession is not yours.” No entire disproof of missionaries, whether of God or of socialism, but they are put in their place, which is both nowhere and here: here only for a scattering of primates, chattering as they browse. Then the bird may start to rattle, voice keeping to a single pitch, and people have called that the “laugh” of the woodpecker.

6.

The painter had a son who might have been played, I realized later, by Peter Lorre. He skulked about, also an artist, almost always regardless of the weather in a fedora and a trench coat and polished shoes. I saw in him what people take for voyeurism or indecent interest: a painter’s love of, not the object, but the composition. To look is often considered a violation, a vice, but this kind of look I, despite my less than minor talent (Paraskeva, by contrast, painted great painting after great painting), know as the fascination and the bliss of viewing the play of relations. It is a form of promiscuity, I concede. Where one thing ends and another begins is perennially open to dispute. Edmund Burke studied the problem in a dove’s neck, in a woman’s breast. We were, in that sense, Burkeans. I love as much as anything on earth the sweet irreconcilable difference of opinion, which makes one nipple point out a different direction than the other. The reasons why professing or pursuing such love is reckoned a scandal and a defect, a sin or sickness under one thumping dispensation or the other, vary by the decade: but the love, its suspense, its slow overflowing, passes so gently where incommensurate reprisals rave and jostle (trying to beat their way out of a state of abstraction), that we cannot refuse to find life itself—person, not personification—, justified beyond rebuttal, in defiance of death and the mortalizers. For by now, even the heel—the vexed tendon—has been dipped in nectareous invulnerability. Thetis, who is always learning, has amended the error, has sanctioned the remedy.

But the painter’s son was strange. He collected enormous numbers of toothbrushes, for example (all colours), and when my sister, admiring one of his streetscape etchings, asked him about its meaning, he pointed to a ONE WAY sign and dilated without humour on the meaning of this signage: “One way to hell.” To fixate on toothbrushes and Tartarean bylaws is to me, to this day, an emblem of what, for whatever reason, I am not. It stands for the strange. Strange! Sometimes he even stole my toothbrush, only to return it later; I boiled it on such occasions, although I do not think he used or abused it. Odd to say, I have met his likes since. No, I am not kidding. I cannot call him unique.

7.

At the time, things might have felt stalled. Certain repertoires played themselves out, over and over again. If I looked around, everyone seemed to be pursuing what pursued them, not a routine but a compulsion. One of my father’s friends dogged him mercilessly over a debt. A friend! My mother grew sicker and sicker, and died. Simultaneous with these fates—very like, when I got round to reading about them, Dante’s pouches and circles of hell—people and objects settled into decay. Settled? Oh no. It was more a case of hollowing out: the forfeiting of intelligence and talent and power: the transition from spontaneous expression to a kind of increasingly inaccurate rote rehearsal. Unable even to move from a chair far more substantial than herself, my mother whispered to me, “I used to be beautiful.” I assured her she still was. She said, “No I am not.” Their striped chins gulping, robins might have pecked at the bare spar perched right next to them as though to find there their phrases, and cocked a blind eye over land they no longer had the music to conjure or renew. Trying their wings, they would find flight, though almost too close, beyond them now.

Imagine, with the return of the rosy morning, the student—ever more incongruously old for his place in school—recites from a set piece, the same assignment, perhaps a sonnet from one of the lesser Elizabethans; more lacunae perforate silently each performance, we can only surmise the former content in the awful pausing of what once were complete quatrains. But oblivion rises proportionately on all sides; the teacher too waxes in incompetence and inattentiveness, the grade assigned never dips or rises; and dilapidation at last ensures the classroom cannot be distinguished from the turf of a cemetery. Now the lawnmower swirls by, its blades dull, sweat darkening the mower’s shirt beneath the armpits in the way moisture spreads from the little crazes that split a tombstone.

The last time I saw Paraskeva Clark, in the 1980s, was at the showing of a documentary about her, in a gallery near Allan Gardens, in Toronto. Fastened to a wheelchair like a sculpture cautiously recovered by divers from the depths of the sea, one of her jaunty hats set by someone else upon her head, she thrust out and she withdrew her dry tongue incessantly. The symptom betokens tardive dyskinesia—consequence of subjection, in a care home, to an intense course of neuroleptic medication. I greeted her, and it was not clear whether she reciprocated from within the gorgon-like grotesquerie imposed by the rhythmical tic that strangled and released her, a vicissitude from which no one could exempt her and which engrossed all the communicative resources of her face.

This vision is not true or was true only in the sense that in a forest it is true, trees grow, trees topple, branches reach, branches blanch and shatter.

But at the time all appeared like wreckage, a human junkyard, people imbibing and devouring poisons, aping an almost lost version of themselves, a sadness it was hard to outwalk or, in a manner of speaking, even to out-sleep. Oh, to hibernate! But we stayed awake the whole winter. You could hear some kind of critic more than magistrate proclaiming: “This person’s strength is past its prime; that person’s gifts wane with every passing night; what she used to say with conviction she now sighs out, not ironic or cynical or despairing—merely bone-weary; as for him, he once stood for something: now he merely is happy to be able to stand up.”

I was surprised, sometimes, looking out the window into cold rain, to scrape from the gloom a patch of honey-yellow, a smear of forsythia, ground though it was under clouds thick as blue clay. Mud tolerated improbable eclosions, as though in the end—but it is not the end—a stele should grow fur, twitchingly discover its musculature, un-fix its feet and, self-enchanted, slinky, live, lope off.

A retrospect, I am convinced, can enter that lost present and coax (if we are to remain Dantean) the dreary party up the slope of Purgatory, no steeper really than the wall of a Toronto ravine.

8.

Biographical notices of Mrs. Clark, the best of which either overdramatize her “tragedy” as a woman, as a Russian, as a mother, as a wife, as an artist, or attempt to spruce up her scary bitterness with despicable cuteness (the merry diversion of cosmeticians in a mortuary, who of course will never themselves die!), say one of her sons was schizophrenic. As a child, I had enough precocity to guess diagnoses do disservice to people. We get unwholesomely excited by labels, it is religion for the one labelled and for those who do the labelling, you are that and I am not, I am this and now I have nothing more to say, to think or to do: it is a relief, it is a dismissal, it is a piece of the worst sort of fiction, an epitaph gouged in living flesh that bleeds out before us even if the living sepulchre thus inscribed staggers on for many decades to come muttering the same formula until a tardy, second death seals the lips. The hell with all fundamentalism! He never advertised himself as ill, or was advertised to me as ill. Instead he was not to be predicted, the opposite of diagnosis. I remember him best by certain engravings he did in sheets of copper with a stylus, darkly glimmering, strong, bringing burning shadows into the brightest room. The epoch marked the heyday of a certain schizophrenia (every syndrome capers like a grave fool, to keep up with fashion), yet no one to my knowledge exploited it in our neglected oxbow lake of the world, or used it as the mallet of fate. I am sad that people will grab any instrument handed to them, and report to the generality, I had a heart attack (for example): I am my heart attack, I swear it by God. They lift their emblematic centre up for our inspection like priests at Chichen Itza, or votaries who in a vision witness Jesus’s bleeding pump. We are made by what force is it to brandish a single defective organ as if it were ourselves?

9.

Regardless, children are heavier than any known metal. In my time, I was one such weight. I could afford to feel light because others, however harassed, sustained me. I once cherished fear of the sky—I still cherish that fear—but now enormous weights hold me down, wet earth is nothing to them for their density and unsearchable core. Obligations! Adults know them. Mrs. Clark had strong arms even to lift a paintbrush at all, the gravity of her planet might have crushed me flat as a picture plane. She lived in another place, though it shared the name Toronto. St. Petersburg, Paris, Leningrad, the unfathomable foundering next door. In the 1930s, she once signed a sketch “Paraskeva Plistik, Paraskeva Allegri, Paraskeva Clark.” At last it does not matter what Mrs. Clark did, her paintings are doing other things at this very moment.

10.

There once dwelt in Westphalia, in the castle of the Baron of Thunder-ten-tronckh, a young man on whom nature had bestowed, if nothing else, the gift and appearance of candour. His teacher, Pangloss, was the best philosopher, his sweetheart Cunégonde the best beloved, and his neighbourhood the most exquisite in the world. Constantinople, Venice, even El Dorado will not unseat it. We all excel, superlative in our provinciality. Whether it be the best or the worst, it exercises absolute dominion. Given this fact of life and geography, and disavowing Voltairean satire—embracing the frankness, rather, of Candide—, let me allow what is obvious: Mrs. Clark remains the best painter on the little globe that perishable force, my experience, has comprehended and compacted. In her painting of what she calls “our street,” made before I was born and before my father swung a mortgage, listen to the wind sounding all the sounds to which high poplars are liable and across and through the top, too, of the opposite side of the ravine. Worked into the gust, wreathed by the rush of freshly breathing leaves, stream the voices of Wood Thrushes as well as of robins. In his cubical house, his magic circle at once binds and frees that infinite figure, the mathematician. In spite of her sorrows—and her convictions—Paraskeva Clark performed and pristinely underwent a rite of prosopopoeia. She gave the world her face (there was some vanity involved in the operation): and the great world in turn, convinced by her offering, lent her, without vanity, its own.

Note: here are the paintings I reproduce.

“Myself,” 1933, National Gallery of Canada

“Swamp,” 1939, Art Gallery of Ontario

“Hydro Workers in Rosedale,” private collection

“Milford Bay Church,” 1956, private collection

“Our Street in Autumn,” 1941-1943, Art Gallery of Ontario