by Thomas O’Dwyer

![Shakespeare & Company, Paris. [Wikipedia]](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SandC.jpg)

Shakespeare and Company is still one of the world’s great bookstores. Its modern touristy ambience does it no favours, but its location in rue de la Bûcherie remains a Paris dreamscape, next to Place Saint-Michel, under the eternal gaze of Notre Dame across the Seine. While the store is a Mecca for book lovers, like other aspects of our angry and divided age, it has noisy detractors as well as champions. When the wandering American ex-serviceman Whitman renamed his existing bookshop Mistral as Shakespeare and Company in 1964, outraged literary purists considered it blatant commercial plagiarism. Sylvia Beach, who famously published James Joyce’s Ulysses when no one else would touch it, had founded her original Shakespeare and Company in 1919 and it remained a legend and writers’ haven at 12 rue de l’Odéon until German Nazi invaders forced its closure in 1941. Although Ernest Hemingway “liberated” it in 1945, Sylvia never reopened it.

In 1958, Sylvia Beach, then 71, accompanied Lawrence Durrell to a reading at Whitman’s Mistral and announced that she was handing the name and the spirit of Shakespeare and Company over to Whitman. Though his critics and some friends of Sylvia Beach have denied this happened, Whitman and Beach had been close friends for many years and he did name his only daughter Sylvia Beach Whitman. Sylvia Whitman inherited the bookstore on George’s death in 2011 and still runs it. Whitman called the name Shakespeare and Company “a novel in three words” and also said he aimed to create “a socialist utopia masquerading as a bookstore”. Whitman could be irascible, but his kindness and generosity were renowned. For decades he offered free accommodation to aspiring writers in return for some help around the store — his literary socialist utopia.

This bookstore remains a defiant challenge to the moaning “death of the bookstores” theme that has pervaded essays about books and publishing since the dawn of the internet. It is not a lone voice in the wilderness. Without resorting to the tedium of statistics about openings and closings of bookshops and sales of books for the last 20 years, there remains enough anecdotal evidence to suggest that book lovers are not deserting bookshops any more than shoe lovers are abandoning their favourite stores. “It is the first thing the pilgrims look up in Paris,” Sylvia Beach wrote in her memoir Shakespeare and Company. This remains true in other cities where hybrid bookshops stock new publications alongside shelves of musty tomes that do smell like grandma’s ancient upholstery. In a recent article in Believer Magazine, Stephen Sparks wrote:

In his late-fifteenth-century woodcut of a danse macabre, Matthias Huss depicts Death striding into a printer’s shop to remind a bookseller and his colleagues of their mortality. When I look at this image now, five centuries later, I find it hard to avoid making a joke that even at the dawn of print, print was pronounced dead.

Maybe it’s time to declare the death of articles whose titles announce “The death of” anything. Newspapers were going to die because of internet users’ appetite for free news. “Look what happened to recorded music because of free illegal downloading,” said the oracles. In 2007 Amazon unleashed the Kindle, which was immediately identified as the grim reaper arriving for printed books. The New Yorker proclaimed the “Twilight of the Books”. Across other media, the winds of change sighed that the slow death of the book was at last upon us.

But then, iTunes and other platforms replaced Napster and it seemed that the alleged freeloaders and pirates were happy to pay for music if they could access it conveniently and legally. New music is still being written and recorded, new performers proliferate and make money. Neither did Amazon’s new spawn of Satan turn out to be Kindle the Killer. It seems instead to have become a global bookstore which is not destroying books but has turned lethargic readers into mass book buyers. Those who buy Kindles start buying content for them at double the rate they previously bought books, and yet they haven’t stopped buying printed books.

When I recently published a book on Amazon, not only could I download it instantly to Kindle, but within a week could parade a dozen printed copies (of excellent quality) on my shelves. There’s not much sign of the death of anything here. E-books are not the inferior enemies of print, they are welcome new immigrants into a territory where is there is ample space for all. No one who has 200 unread books on their Kindle is throwing out the 300 unread books in their home library, but are probably adding to them as well.

Others demur. In a poignant short memoir, I Murdered my Library, novelist Linda Grant shared her agonising decision to get rid of a lifetime’s collection of books when she moved from her apartment in London. “The idea that I was building a library to bequeath to the next generation is one of the greatest fallacies of my life. The next generation doesn’t want old books — they don’t seem to want books at all,” she writes. She may be correct — there are disturbing signs that the youngest generations’ lack of interest in owning books could be the real writing on the wall of doom.

Grant feared that her ruthlessness might turn her into a thoroughly shameful character — a professional author with no books on her home shelves. She even junked accumulated copies of her own novels, albeit with a plaintive note of hope: “However systematically you try to destroy them, there is always a chance that a copy will survive and continue to enjoy a shelf-life in some corner of an out-of-the-way library somewhere, in Reykjavik, Valladolid or Vancouver.” Or, more likely, in some corner of an out-of-the-way secondhand bookshop in Lisbon or Nicosia or Tel Aviv, nestling in a universal homely atmosphere, amid that smell of discarded books waiting to be rediscovered.

It is astonishing how many English-language bookshops one can discover in faraway places where English isn’t spoken. Off a barely visible side-alley in central Tel Aviv, there is Halper’s secondhand bookshop, a typical such store of creaking shelves and narrow passageways that is home to 60,000 books plus an unknown number of collectables in storage. On a brief visit, I left with two editions of books I last saw when I was 15 years old, Heinrich Harrer’s Seven Years in Tibet and the paperback of Iris Murdoch’s first novel Under the Net.

Similarly in Nicosia, I found a real treasure in the Moufflon Bookshop just outside the Venetian walls of the old town, a short walk from the line separating Greeks and Turks in the world’s last divided capital. Predominantly an English-language store, Moufflon has an amazing panorama of books on Cyprus, the Levant and the East Mediterranean. There I found Volume III of George Hill’s 1947 History of Cyprus which I had been hunting for years for its brilliant retelling of the Venetian occupation of Cyprus under Queen Caterina Cornaro.

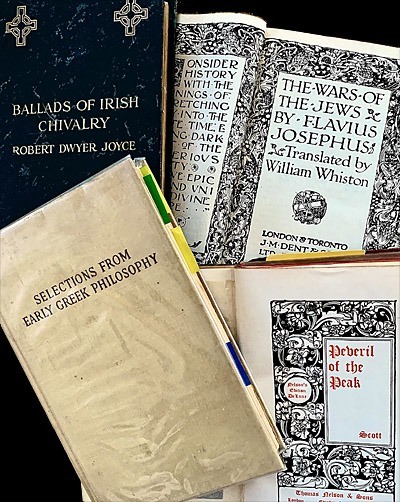

Shaun Bythell in his Confessions of a Bookseller published this year writes: “There does seem to be a serendipity about bookshops, not just with finding books you never knew existed, or that you’ve been searching for, but with people too”. The first secondhand book I found, and still possess, was in a disused table drawer when I was about ten. It was a compact red cloth-covered volume, 500 pages of small print, titled The Wars of the Jews by the Roman historian Flavius Josephus. What’s this, I asked my father. “Don’t know,” he said. “It was in a bundle of books I found in a Wexford shop when I was in the army.” Inside it says, “First printed 1915. This edition reprinted 1928.” Again, that fragrance — who knows, dust, glue, paper, the droppings of a bookworm, perhaps.

That’s still an aura to the secondhand bookshop, no matter where. It’s in the cosy fug of the Libreria Internazionale Marco Polo in the Cannaregio district of Venice. Like all good old bookstores, it has threads linked to ancient times. Marco Polo himself lived nearby, close to the Teatro Malibran, when he wasn’t rambling around China. There is the essential decrepit homely atmosphere, the press of orphaned books and the outside air full of canal water, gossip and learning. Shakespeare and Company set the musty standard (or lack of it) — run to seed a bit, corridors and narrow stairs to try the patience of Ariadne, eccentric moody owners, writers wandering in and out, pretentious tourists self-promoting in American or London City accents.

These are bookshops where the atmosphere, characters, stories and intrigue that should be in the novels on the shelves seem to have become detached and taken over the whole premises. Of course, such romantic blather only takes us so far. These places must sell books, make a profit, pay the rent, feed and clothe the employees and their families. If we think we should have only the atmosphere and illusions, that we enter to browse but not to buy, then soon we will indeed have no more bookshops.

A lesser-known extension of the international secondhand bookshop is the book town. The most famous member of this odd family is Hay-on-Wye, a small market town on the border of England and Wales. In the 1960s the fortunes of this village, population 1,600, became dependent on the power of books. A businessman, Richard Booth, opened a secondhand bookshop which became popular and grew to become one of Britain’s largest. Other specialist and secondhand bookshops opened in the town establishing new bibliophile credentials that attracted weekend crowds from surrounding counties. Hay, now the world’s first book town, staged a literary festival in 1987 which remains the leading such event in Britain attracting tens of thousands of visitors each year (before our pandemic days).

In 1979, a Belgian tourist returned home from visiting Hay-on-Wye and was inspired to copy the model to his little village (Redu, population 500) in the Ardennes region. Villager Noel Anselot invited regional booksellers to set up shops in barns, houses, and farm buildings and transformed the village into a minor Hay with a score of secondhand bookshops. The concept was repeated in the small Catskills town of Hobart, New York, in Fjaerland on the fjords of Norway, and in Wigtown, Scotland.

Graham Greene, an ardent supporter of small bookshops who lauded the glamour and romance of the bookselling trade, wrote that “secondhand booksellers are the most friendly and most eccentric of all the characters I have known.” In a foreword to a memoir by the biographer and bookseller John Baxter, A Pound of Paper, Greene wrote: “If I had not been a writer, theirs would have been the profession I would most happily have chosen.” A Scottish journalist and mystery writer, Augustus Muir, also wrote of Baxter’s extraordinary dedication to his profession as a seller of books:

He handled the books with the reverence of a minister opening the pulpit bible. He had polished the leather that morning till it gleamed like silk, and his finger-tips rested upon it as if they were butterflies alighting on a choice flower. He seemed to purr with pleasure at the contact.

Much is written about the strange people who open secondhand bookstores and spend their entire precarious lives running them, but in Shaun Bythell’s memoir, he casts a gentle eye on the equally strange customers who frequent these places. Bythell runs his shop in Wigtown, Scotland, one of the famous book towns mentioned above, where he slyly observes such types as “the person who doesn’t know what they want (but thinks it might have a blue cover)” and the Expert, who comes in a range of flavours from the crushing bore to the really helpful. They are all quite recognisable and you will spot at least one type the next time you look in a mirror.

There’s the Loiterer, usually found skulking in the erotica section, or the Self-published, fussily seeking out their own titles, which of course are never there. There are bearded pensioners and Lycra-clad cyclists complete with helmets, and the Not-So-Silent Traveller, humming, sniffing, tut-tutting and farting his way from section to section before leaving without buying anything. Many come for tactile meditation-by-browsing. Others enjoy attendant social benefits like authors’ readings, piles of magazines, in-store coffee, maybe warm chairs to sink into on a wet November afternoon. In Paris, George Whitman used to host breakfasts for random strangers in a tiny upstairs room. It was awkward, as conversations turned stilted when the tourists tried to improvise the role of salon literati when it was obvious most hadn’t read a serious book in years. So, despite Bythell’s witty observations, it would seem that neither the owners nor the customers are the important parts of the secondhand bookstore ecology. Agatha Christie for one knew exactly who is in charge:

It is clear that the books owned the shop rather than the other way about. Everywhere they had run wild and taken possession of their habitat, breeding and multiplying, and clearly lacking any strong hand to keep them down. (The Clocks)