by Omar Baig

Chris Green is the Executive Director of Harvard Law School’s Animal Law & Policy Program; the former Chair of the American Bar Association’s Animal Law Committee; and previously was the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Animal Legal Defense Fund. In those capacities, Green persuaded the top three US airlines to stop transporting endangered animal hunting trophies, helped defeat Ag-Gag legislation in several states, and passed two ABA resolutions that recommended 1) outlawing the possession of dangerous wild animals, and 2) providing non-lethal animal encounter training to officers. He recently served on a National Academies of Sciences committee, which recommended that the Dept. of Veterans Affairs substantially reduce its use of dogs in biomedical research. Green is a graduate of Harvard Law School and the University of Illinois: where he created the college’s first Environmental Science degree. He also works in the fine arts, film, and music industries, producing several documentaries, including the film Of Dogs and Men about police shooting people’s pets.

Congratulations on the news of a $10 million endowment for the Animal Law & Policy Program by the Brooks Institute. Could you discuss the Harvard Law School’s previous and ongoing collaboration with the Brooks Institute, like the Brooks Animal Law Digest?

Four years ago, Professor Kristen Stilt, the Animal Law & Policy Program’s Faculty Director, and I met with the Brooks Institute’s Executive Director, Tim Midura. The two of us offered our knowledge and experience to help strategize how the greatest impact could be made. Kristen then became one of the Brooks Institute’s advisers––serving on its Executive Committee, Scholars Committee, and the Leadership Committee of both the Brooks Animal Studies Academic Network and the Brooks Animal Sentience and Cognition Initiative.

We could not be prouder to have our work recognized in this manner and are honored that our Program will now bear the name of Brooks McCormick Jr.––who cared so deeply about the treatment of nonhuman animals. Read more »

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!

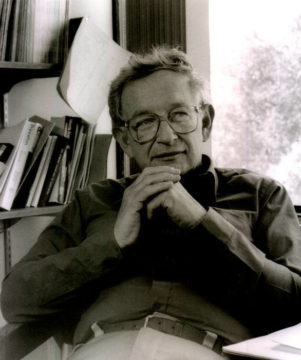

Tick, Tick . . . Boom! Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

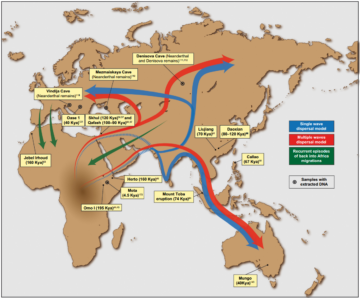

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors  hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter.

hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter. Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?  It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.