by Ada Bronowski

The encounter between Oedipus and the Sphinx has always represented the encounter between two incompatible worlds: chaos versus reason, myth versus history, woman against man, enigmatic verbosity against crystal-clear clarity. Only one of these worlds can survive the clash.

The Sphinx’s riddle: what stays the same yet walks on four feet in the morning, two at midday and three in the evening, is solved by Oedipus who says that it is man, who crawls on all four as a baby, walks on two feet in his prime and with the aid of a stick, and thus on three legs, in his old-age. With this answer, Oedipus came to his own not as Oedipus, the individual, but as a figure of modern man, dispelling the forces of darkness that reigned terror on helpless mortals. Overcoming the Sphinx was – it seemed – like a new beginning, in which man-made laws became the one true law, and wild nature was tamed by human rationality.

As the Sphinx threw itself off a cliff, it buried with it the unwieldly, monstrous side of nature, and Oedipus was hailed not as ‘one amongst the gods’ as so often with Greek heroes, but ‘as a mortal, first amongst men, who disarmed the supernatural forces’, (at the beginning of Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, l.31-4). Of course, we know what happened next. Man-made law and order did not stand a chance in the face of parricide, incest and children that are also siblings. The dark forces soon took hold of Oedipus and of Thebes once more, to the extent that one suspects they never left in the first place. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in The November Sun, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in The November Sun, 2020.

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant.

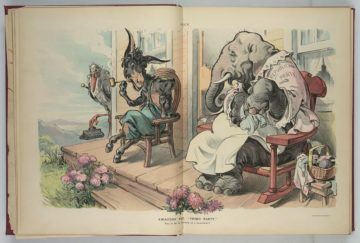

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant. The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve.

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve. My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom.

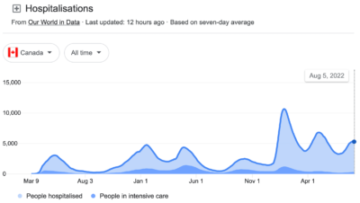

My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom. A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.