by Mike Bendzela

How would you account for the following weird experience? Do you have a handy explanation, or do you dismiss it outright?

When I was twelve, Dad used to drop me off in the twilight in front of the parish across town to serve Mass, usually a Wednesday before dawn, because that was the time new altar boys served their shifts.

“Pray for me,” Dad would say as I got out of the car, “and for your poor mother’s soul.” He parked the car far down the block and sat there in the dark waiting for me to return from Mass — swigging whisky, I now assume, from his paper bag all the while.

The time I spent with my fellow altar boy, Michael, was a refuge from the horrors of home. We got dressed together, laid out brass artifacts and towels and books together, lit candles together. The priest who had my dad excommunicated was more than kind to me, and groomed me for the priesthood with effusiveness and, I saw later, with the intent to elevate me above my fallen parents. I didn’t want to leave the sacristy; I didn’t want to go back to my dad’s car; I wanted to camp out there with Michael, forever. Perhaps he and I could both become priests and secretly live there in the rectory. I even passed this by Father Frank.

He looked at me with something like triumph and affection. “It is not outside the realm of possibility,” he said.

After Mass, I nearly flew back to the car.

Once I was inside, dad asked, “Did you pray for us?”

I stared blankly. In my excitement about moving into the church with Michael, I had forgotten all about my ritual prayer for my parents.

The back story was something I would only learn much later from an aunt: During a rough spot in their marriage, my mother had become pregnant by another man, and Dad decided she should have an abortion (then illegal in our state); he took her where she could get one, and she died of sepsis. My father was consequently forbidden from setting foot in the Catholic Church he was raised in, even though he was prostrate with grief and remorse. He could do nothing to assuage the pain, not even drink it away. Read more »

The international academic conference circuit—for an amusing account of such circuits, one may read the British writer David Lodge’s novel Small World, which is second in his trilogy of campus novels, the first of which Changing Places is largely on Berkeley in the 1960’s—also brought me to some potentially hazardous situations. Once a reception given for us conference participants by the King of Spain indirectly helped me in what could have been a serious loss from a pickpocket in Madrid. The public reception hall was not far from the hotel where we were staying. I was walking there from the hotel with a fellow conference participant. I was busy explaining a particular point to her in conversation when I had a half-sense that two young women who brushed by seemed a bit too close, and I ignored that for a minute. The next minute I felt the inside of my jacket pocket and it was gone—a wallet containing not just money but a few important cards including credit cards (since then I have been careful not to put everything in the same wallet or pocket). So I excused myself from my companion and ran to a nearby policeman and told him about it. He brought out a whistle and made a signaling sound. Within 5 minutes another policeman from the opposite pavement came toward me with my wallet and asked me to check if everything was in place. Those two unlucky young women did not realize that as the King was to be there soon, the whole area was thick with plain-clothes policemen.

The international academic conference circuit—for an amusing account of such circuits, one may read the British writer David Lodge’s novel Small World, which is second in his trilogy of campus novels, the first of which Changing Places is largely on Berkeley in the 1960’s—also brought me to some potentially hazardous situations. Once a reception given for us conference participants by the King of Spain indirectly helped me in what could have been a serious loss from a pickpocket in Madrid. The public reception hall was not far from the hotel where we were staying. I was walking there from the hotel with a fellow conference participant. I was busy explaining a particular point to her in conversation when I had a half-sense that two young women who brushed by seemed a bit too close, and I ignored that for a minute. The next minute I felt the inside of my jacket pocket and it was gone—a wallet containing not just money but a few important cards including credit cards (since then I have been careful not to put everything in the same wallet or pocket). So I excused myself from my companion and ran to a nearby policeman and told him about it. He brought out a whistle and made a signaling sound. Within 5 minutes another policeman from the opposite pavement came toward me with my wallet and asked me to check if everything was in place. Those two unlucky young women did not realize that as the King was to be there soon, the whole area was thick with plain-clothes policemen.

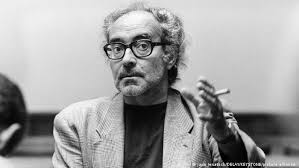

On the 13th September 2022, Jean-Luc Godard, the Franco-Swiss film-director, film-poet, film-philosopher, died at the age of 91. One of the most imaginative, rebellious, truly courageous artists on this planet whose existence, in more ways than can be enumerated in language, changed the face of our modernity, decided to end his life through assisted suicide, which is a legal practice in Switzerland, the country he had been living in since 1976, and in which he had spent his youth. He was not ill, ‘but exhausted’. In addition to everything else, his last action resonates with a magnitude that is as powerful as a political stand as it is as a last demonstration of a personal ethics which can be summarised as: moral integrity or nothing. A moral integrity, which he brought to bear indefatigably over the course of a lifetime in pursuit of freedom, resolution and independence – at whatever price.

On the 13th September 2022, Jean-Luc Godard, the Franco-Swiss film-director, film-poet, film-philosopher, died at the age of 91. One of the most imaginative, rebellious, truly courageous artists on this planet whose existence, in more ways than can be enumerated in language, changed the face of our modernity, decided to end his life through assisted suicide, which is a legal practice in Switzerland, the country he had been living in since 1976, and in which he had spent his youth. He was not ill, ‘but exhausted’. In addition to everything else, his last action resonates with a magnitude that is as powerful as a political stand as it is as a last demonstration of a personal ethics which can be summarised as: moral integrity or nothing. A moral integrity, which he brought to bear indefatigably over the course of a lifetime in pursuit of freedom, resolution and independence – at whatever price.

The only thing worse than a good argument contrary to a conviction you hold is a bad argument in its favor. Overcoming a good argument can strengthen your position, while failing to may prompt you to reevaluate it. In either case, you’ve learned something—if perhaps at the expense of a cherished belief.

The only thing worse than a good argument contrary to a conviction you hold is a bad argument in its favor. Overcoming a good argument can strengthen your position, while failing to may prompt you to reevaluate it. In either case, you’ve learned something—if perhaps at the expense of a cherished belief.