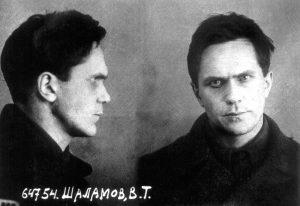

Varlam Shalamov in the Paris Review:

For fifteen years the writer Varlam Shalamov was imprisoned in the Gulag for participating in “counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activities.” He endured six of those years enslaved in the gold mines of Kolyma, one of the coldest and most hostile places on earth. While he was awaiting sentencing, one of his short stories was published in a journal called Literary Contemporary. He was released in 1951, and from 1954 to 1973 he worked on Kolyma Stories, a masterpiece of Soviet dissident writing that has been newly translated into English and published by New York Review Books Classics this week. Shalamov claimed not to have learned anything in Kolyma, except how to wheel a loaded barrow. But one of his fragmentary writings, dated 1961, tells us more.

For fifteen years the writer Varlam Shalamov was imprisoned in the Gulag for participating in “counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activities.” He endured six of those years enslaved in the gold mines of Kolyma, one of the coldest and most hostile places on earth. While he was awaiting sentencing, one of his short stories was published in a journal called Literary Contemporary. He was released in 1951, and from 1954 to 1973 he worked on Kolyma Stories, a masterpiece of Soviet dissident writing that has been newly translated into English and published by New York Review Books Classics this week. Shalamov claimed not to have learned anything in Kolyma, except how to wheel a loaded barrow. But one of his fragmentary writings, dated 1961, tells us more.

1. The extreme fragility of human culture, civilization. A man becomes a beast in three weeks, given heavy labor, cold, hunger, and beatings.

2. The main means for depraving the soul is the cold. Presumably in Central Asian camps people held out longer, for it was warmer there.

3. I realized that friendship, comradeship, would never arise in really difficult, life-threatening conditions. Friendship arises in difficult but bearable conditions (in the hospital, but not at the pit face).

4. I realized that the feeling a man preserves longest is anger. There is only enough flesh on a hungry man for anger: everything else leaves him indifferent.

More here.

My students and I were in the midst of studying Learning from Las Vegas when the news came of Robert Venturi’s death. We had just absorbed an extraordinary lecture tour of his mother’s house, in all its faux–New England simplicity, which harbored so many allusive surprises; now the book, published in 1972, was revealing itself to be a profoundly American source for the cultural-studies movement whose genealogy we had for so long attributed to the Birmingham School. It also turns out to have been one of the underground blasts that signaled the beginning of postmodernism.

My students and I were in the midst of studying Learning from Las Vegas when the news came of Robert Venturi’s death. We had just absorbed an extraordinary lecture tour of his mother’s house, in all its faux–New England simplicity, which harbored so many allusive surprises; now the book, published in 1972, was revealing itself to be a profoundly American source for the cultural-studies movement whose genealogy we had for so long attributed to the Birmingham School. It also turns out to have been one of the underground blasts that signaled the beginning of postmodernism. The grand term ‘intellectual property’ covers a lot of ground: the software that runs our lives, the movies we watch, the songs we listen to. But also the credit-scoring algorithms that determine the contours of our futures, the chemical structure and manufacturing processes for life-saving pharmaceutical drugs, even the golden arches of McDonald’s and terms such as ‘Google’. All are supposedly ‘intellectual property’. We are urged, whether by stern warnings on the packaging of our Blu-ray discs or by sonorous pronouncements from media company CEOs, to cease and desist from making unwanted, illegal or improper uses of such ‘property’, not to be ‘pirates’, to show the proper respect for the rights of those who own these things. But what kind of property is this? And why do we refer to such a menagerie with one inclusive term?

The grand term ‘intellectual property’ covers a lot of ground: the software that runs our lives, the movies we watch, the songs we listen to. But also the credit-scoring algorithms that determine the contours of our futures, the chemical structure and manufacturing processes for life-saving pharmaceutical drugs, even the golden arches of McDonald’s and terms such as ‘Google’. All are supposedly ‘intellectual property’. We are urged, whether by stern warnings on the packaging of our Blu-ray discs or by sonorous pronouncements from media company CEOs, to cease and desist from making unwanted, illegal or improper uses of such ‘property’, not to be ‘pirates’, to show the proper respect for the rights of those who own these things. But what kind of property is this? And why do we refer to such a menagerie with one inclusive term? For all its economic might, Germany’s main centrist parties are

For all its economic might, Germany’s main centrist parties are  The latest TV series by charming, tidy-up guru Marie Kondo

The latest TV series by charming, tidy-up guru Marie Kondo  A deep-learning algorithm is helping doctors and researchers to pinpoint a range of rare genetic disorders by analysing pictures of people’s faces. In a paper

A deep-learning algorithm is helping doctors and researchers to pinpoint a range of rare genetic disorders by analysing pictures of people’s faces. In a paper

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend  My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.

When contemporary atheists criticise religious beliefs, they usually criticise beliefs that only crude religious thinkers embrace. Or so some people claim. The beliefs of the sophisticated religious believer, it’s suggested, are immune to such assaults.

When contemporary atheists criticise religious beliefs, they usually criticise beliefs that only crude religious thinkers embrace. Or so some people claim. The beliefs of the sophisticated religious believer, it’s suggested, are immune to such assaults. Recently I’ve been experimenting with mood-modification through temperature extremes (like

Recently I’ve been experimenting with mood-modification through temperature extremes (like  The state in polities broadly described as ‘liberal democracies’ with political economies broadly described as ‘capitalist’ are characterised by a feature that Gramsci called ‘hegemony’. This is a technical term, not to be confused with the loose use of that term to connote ‘power and domination over another’. In Gramsci’s special sense, hegemony means that a class gets to be the ruling class by convincing all other classes that its interests are the interests of all other classes. It is because of this feature that such states avoid being authoritarian. Authoritarian states need to be authoritarian precisely because they lack Gramscian hegemony. It would follow from this that if a state that does possess hegemony in this sense is authoritarian, there is something compulsive about its authoritarianism. Now, what is interesting is that the present government in India keeps boastfully proclaiming that it possesses hegemony in this sense, that it has all the classes convinced that its policies are to their benefit. If so, one can only conclude that its widely recorded authoritarianism, therefore, is pathological.

The state in polities broadly described as ‘liberal democracies’ with political economies broadly described as ‘capitalist’ are characterised by a feature that Gramsci called ‘hegemony’. This is a technical term, not to be confused with the loose use of that term to connote ‘power and domination over another’. In Gramsci’s special sense, hegemony means that a class gets to be the ruling class by convincing all other classes that its interests are the interests of all other classes. It is because of this feature that such states avoid being authoritarian. Authoritarian states need to be authoritarian precisely because they lack Gramscian hegemony. It would follow from this that if a state that does possess hegemony in this sense is authoritarian, there is something compulsive about its authoritarianism. Now, what is interesting is that the present government in India keeps boastfully proclaiming that it possesses hegemony in this sense, that it has all the classes convinced that its policies are to their benefit. If so, one can only conclude that its widely recorded authoritarianism, therefore, is pathological.