Julie Cadman-Kim in MQR:

In Dur e Aziz Amna’s gorgeous debut, American Fever, readers can expect to find all the hallmarks of a bumpy adolescence—destructive confidence, crippling self-doubt, steamy crushes, social gaffes, obsession with looks and style, and pervasive loneliness. But within this jewel-box of a novel, these universal qualities unfold in a most unusual situation.

In Dur e Aziz Amna’s gorgeous debut, American Fever, readers can expect to find all the hallmarks of a bumpy adolescence—destructive confidence, crippling self-doubt, steamy crushes, social gaffes, obsession with looks and style, and pervasive loneliness. But within this jewel-box of a novel, these universal qualities unfold in a most unusual situation.

In late 2010, sixteen-year-old Hira is eager to leave Pakistan and begin a year-long exchange program in America. Only when she arrives in a woefully rural corner of the country, nothing quite measures up to her expectations. Hira’s host family seems to want little to do with her, her new high school is full of ignorant hayseeds, and she struggles even to get enough food to eat. To top it off, she’s falling in love with an older guy across the country, in New York, and carrying a dormant strain of tuberculosis. Underfed and way outside her comfort zone, she begins to deteriorate until her weakened immune system allows the virus to bloom, wreaking havoc not only on Hira, but also on the fragile community she’s built around herself.

All my life, I have observed a certain kind of person with baffled envy. The person who has never felt the desire to flee. I feel the least in common with this person, and yet I am endlessly fascinated by her. How can one be that content? Is she lucky, the draw of the universe birthing her in a place that fully aligns with her in temperament and ambition, or is she just complacent?

Throughout the novel, Hira must navigate complex cultural waters and a cloistered new reality in which self-preservation and personal growth are difficult to balance. She is expected to play ambassador, brush off xenophobic taunts, and feel grateful for all the United States has to offer, but the longer she spends in the U.S., the more she second-guesses exactly what she believes in and her decision to leave Pakistan in the first place. At the same time, she’s drawn more than ever to memories and ideals from home, the distance helping illuminate who she is and the magnitude of what she was so eager to leave behind.

More here.

In my essay “No one will read your book,” I said that publishing houses work more like venture capitalists. They invest small sums in lots of books in hopes that one of them breaks out and becomes a unicorn, making enough money to fund all the rest.

In my essay “No one will read your book,” I said that publishing houses work more like venture capitalists. They invest small sums in lots of books in hopes that one of them breaks out and becomes a unicorn, making enough money to fund all the rest.

Start talking to

Start talking to  If we do pay attention, it is not hard to see that capital’s mutation into what I call cloud capital has demolished capitalism’s two pillars: markets and profits. Of course, markets and profits remain ubiquitous—indeed, markets and profits were ubiquitous under feudalism too—they just aren’t running the show anymore. What has happened over the last two decades is that profit and markets have been evicted from the epicenter of our economic and social system, pushed out to its margins, and replaced. With what? Markets, the medium of capitalism, have been replaced by digital trading platforms which look like, but are not, markets, and are better understood as fiefdoms. And profit, the engine of capitalism, has been replaced with its feudal predecessor: rent. Specifically, it is a form of rent that must be paid for access to those platforms and to the cloud more broadly. I call it cloud rent. As a result, real power today resides not with the owners of traditional capital, such as machinery, buildings, railway and phone networks, industrial robots. They continue to extract profits from workers, from waged labor, but they are not in charge as they once were. They have become vassals in relation to a new class of feudal overlord, the owners of cloud capital. As for the rest of us, we have returned to our former status as serfs, contributing to the wealth and power of the new ruling class with our unpaid labor—in addition to the waged labor we perform, when we get the chance.

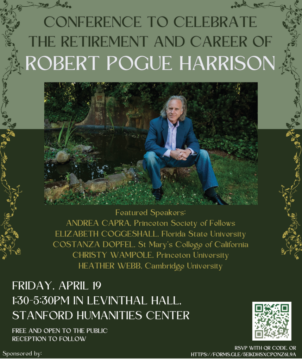

If we do pay attention, it is not hard to see that capital’s mutation into what I call cloud capital has demolished capitalism’s two pillars: markets and profits. Of course, markets and profits remain ubiquitous—indeed, markets and profits were ubiquitous under feudalism too—they just aren’t running the show anymore. What has happened over the last two decades is that profit and markets have been evicted from the epicenter of our economic and social system, pushed out to its margins, and replaced. With what? Markets, the medium of capitalism, have been replaced by digital trading platforms which look like, but are not, markets, and are better understood as fiefdoms. And profit, the engine of capitalism, has been replaced with its feudal predecessor: rent. Specifically, it is a form of rent that must be paid for access to those platforms and to the cloud more broadly. I call it cloud rent. As a result, real power today resides not with the owners of traditional capital, such as machinery, buildings, railway and phone networks, industrial robots. They continue to extract profits from workers, from waged labor, but they are not in charge as they once were. They have become vassals in relation to a new class of feudal overlord, the owners of cloud capital. As for the rest of us, we have returned to our former status as serfs, contributing to the wealth and power of the new ruling class with our unpaid labor—in addition to the waged labor we perform, when we get the chance. It is today my belief that once ordinary language is laughed out of the room, philosophical theories are no longer held responsible at all to the ways we actually speak and actually live. And aren’t the humanities ultimately for a good part connected to how we actually speak and live? To me, it is clear that the descriptions of human life we find in the novels of Samuel Beckett or in the poetry of Giacomo Leopardi are not mere entertainment. In my view, and among other things, they teach us to perceive and describe what goes on in social and individual life. To echo what Hilary Putnam once said, contempt for ordinary language is, at bottom, contempt for the humanities.

It is today my belief that once ordinary language is laughed out of the room, philosophical theories are no longer held responsible at all to the ways we actually speak and actually live. And aren’t the humanities ultimately for a good part connected to how we actually speak and live? To me, it is clear that the descriptions of human life we find in the novels of Samuel Beckett or in the poetry of Giacomo Leopardi are not mere entertainment. In my view, and among other things, they teach us to perceive and describe what goes on in social and individual life. To echo what Hilary Putnam once said, contempt for ordinary language is, at bottom, contempt for the humanities. T

T What would it mean to subtract context from writing, in each and every sense of “context” that Derrida proposes here? And would this be a remotely helpful exercise for thinking about the relation between text and context in literary studies? It’s hard to see how it could be. Even the strongest statements I can think of urging critics to turn away from context—take Rita Felski’s essay “Context Stinks!,” the last chapter of her Limits of Critique, or Joseph North’s arguments against the historicist/contextualist paradigm in Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History—even these apparently hardline positions in no way advocate for a total absenting of every form of contextual consideration. Rather, each seeks to limit appeals to certain contexts in order to boost the visibility of others. North, for example, seeks to challenge the priority placed on historical scholarship in order to shed light on present contexts of aesthetic education. For him, historical scholarship has become overly specialized and no longer realizes its vocation “to intervene in the ‘culture as a whole.’”

What would it mean to subtract context from writing, in each and every sense of “context” that Derrida proposes here? And would this be a remotely helpful exercise for thinking about the relation between text and context in literary studies? It’s hard to see how it could be. Even the strongest statements I can think of urging critics to turn away from context—take Rita Felski’s essay “Context Stinks!,” the last chapter of her Limits of Critique, or Joseph North’s arguments against the historicist/contextualist paradigm in Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History—even these apparently hardline positions in no way advocate for a total absenting of every form of contextual consideration. Rather, each seeks to limit appeals to certain contexts in order to boost the visibility of others. North, for example, seeks to challenge the priority placed on historical scholarship in order to shed light on present contexts of aesthetic education. For him, historical scholarship has become overly specialized and no longer realizes its vocation “to intervene in the ‘culture as a whole.’” Evidently, the time is ripe for a survey of the branch of cultural production concerned with the end of the world. And yet, as Lynskey points out, tales have been told about it for as long as we’ve been doing story. J G Ballard, whose work is given rich and perceptive attention in the chapter ‘Catastrophe’, wrote in 1977: ‘I would guess that from man’s first inkling of this planet as a single entity existing independently of himself came the determination to bring about its destruction.’

Evidently, the time is ripe for a survey of the branch of cultural production concerned with the end of the world. And yet, as Lynskey points out, tales have been told about it for as long as we’ve been doing story. J G Ballard, whose work is given rich and perceptive attention in the chapter ‘Catastrophe’, wrote in 1977: ‘I would guess that from man’s first inkling of this planet as a single entity existing independently of himself came the determination to bring about its destruction.’ Most of us think of inflammation as the redness and swelling that follow a wound, infection or injury, such as an ankle sprain, or from overdoing a sport, “tennis elbow,” for example. This is “acute” inflammation, a beneficial immune system response that encourages healing, and usually disappears once the injury improves.

Most of us think of inflammation as the redness and swelling that follow a wound, infection or injury, such as an ankle sprain, or from overdoing a sport, “tennis elbow,” for example. This is “acute” inflammation, a beneficial immune system response that encourages healing, and usually disappears once the injury improves. Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by  In need of silence, I booked a room at a Trappist monastery. The following Friday, I snuck out of work early and headed south, not realizing that Ava, Missouri, was four hours away, down at the border of Arkansas. I sped down the interstate, glided off the exit ramp—and got stuck behind a livestock trailer. For the next hour, as we crept along a narrow country road, the wide face of a brown and white cow gazed back at me. Its fuzzy ears stuck straight out, like they had been glued on at the last minute. Lashes curled above steady brown eyes that held a lifetime’s observations.

In need of silence, I booked a room at a Trappist monastery. The following Friday, I snuck out of work early and headed south, not realizing that Ava, Missouri, was four hours away, down at the border of Arkansas. I sped down the interstate, glided off the exit ramp—and got stuck behind a livestock trailer. For the next hour, as we crept along a narrow country road, the wide face of a brown and white cow gazed back at me. Its fuzzy ears stuck straight out, like they had been glued on at the last minute. Lashes curled above steady brown eyes that held a lifetime’s observations. The endangered bonobo, the great ape of the Central African rainforest, has a reputation for being a bit of a hippie. Known as more peaceful than their warring chimpanzee cousins, bonobos live in matriarchal societies, engage in recreational sex, and display signs of

The endangered bonobo, the great ape of the Central African rainforest, has a reputation for being a bit of a hippie. Known as more peaceful than their warring chimpanzee cousins, bonobos live in matriarchal societies, engage in recreational sex, and display signs of  I do not deny that there has been a shocking and upsetting rise in antisemitism over the last few months, including several instances of antisemitism right at Yale and in New Haven. Last fall, one professor’s post on X (formerly Twitter) appearing to praise Hamas’ October 7th attack sparked a petition for her to be fired.

I do not deny that there has been a shocking and upsetting rise in antisemitism over the last few months, including several instances of antisemitism right at Yale and in New Haven. Last fall, one professor’s post on X (formerly Twitter) appearing to praise Hamas’ October 7th attack sparked a petition for her to be fired.

In Dur e Aziz Amna’s gorgeous debut, American Fever, readers can expect to find all the hallmarks of a bumpy adolescence—destructive confidence, crippling self-doubt, steamy crushes, social gaffes, obsession with looks and style, and pervasive loneliness. But within this jewel-box of a novel, these universal qualities unfold in a most unusual situation.

In Dur e Aziz Amna’s gorgeous debut, American Fever, readers can expect to find all the hallmarks of a bumpy adolescence—destructive confidence, crippling self-doubt, steamy crushes, social gaffes, obsession with looks and style, and pervasive loneliness. But within this jewel-box of a novel, these universal qualities unfold in a most unusual situation.