Sabine Hossenfelder in Back Reaction:

In recent years many prominent people have expressed worries about artificial intelligence (AI). Elon Musk thinks it’s the “biggest existential threat.” Stephen Hawking said it could “be the worst event in the history of our civilization.” Steve Wozniak believes that AIs will “get rid of the slow humans to run companies more efficiently,” and Bill Gates, too, put himself in “the camp that is concerned about super intelligence.”

In recent years many prominent people have expressed worries about artificial intelligence (AI). Elon Musk thinks it’s the “biggest existential threat.” Stephen Hawking said it could “be the worst event in the history of our civilization.” Steve Wozniak believes that AIs will “get rid of the slow humans to run companies more efficiently,” and Bill Gates, too, put himself in “the camp that is concerned about super intelligence.”

In 2015, the Future of Life Institute formulated an open letter calling for caution and formulating a list of research priorities. It was signed by more than 8,000 people.

Such worries are not unfounded. Artificial intelligence, as any new technology, brings risks. While we are far from creating machines even remotely as intelligent as humans, it’s only smart to think about how to handle them sooner rather than later.

However, these worries neglect the more immediate problems that AI will bring.

More here.

Iraq has endured decades of sanctions, war, invasion, regime change and dysfunctional government. These span Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, a devastating eight-year war with Iran in the 1980s and crippling UN sanctions throughout the 1990s. Those difficult years gave way to the traumas of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion and its chaotic aftermath, which brought the insurgents of the Islamic State to the outskirts of the Iraqi capital Baghdad in 2014.

Iraq has endured decades of sanctions, war, invasion, regime change and dysfunctional government. These span Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, a devastating eight-year war with Iran in the 1980s and crippling UN sanctions throughout the 1990s. Those difficult years gave way to the traumas of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion and its chaotic aftermath, which brought the insurgents of the Islamic State to the outskirts of the Iraqi capital Baghdad in 2014. Few issues in economics have generated such heated debates as the nature of money and its role in the economy. What is money? How is it related to debt? How does it influence economic activity? The recent mainstream economic literature is an unfortunate exception. Bar a few who have sailed into these waters, money has been allowed to sink by the macroeconomics profession. And with little or no regrets.

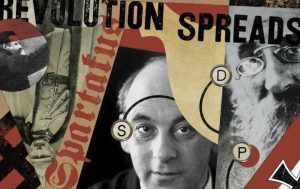

Few issues in economics have generated such heated debates as the nature of money and its role in the economy. What is money? How is it related to debt? How does it influence economic activity? The recent mainstream economic literature is an unfortunate exception. Bar a few who have sailed into these waters, money has been allowed to sink by the macroeconomics profession. And with little or no regrets. It was slightly more than a century ago, in November 1918, that revolution swept through Germany, bringing chaos to a country that, in the final days of World War I, was already in desperate straits and verging on collapse. Although it was obvious to nearly everyone that the war was lost, the fighting staggered on, even as a growing pacifist movement issued the cry for “Peace, Freedom, Bread!” In Kiel on the Baltic Sea, sailors at the docks refused the order for a last battle and went into open mutiny, while soldiers and revolutionary workers in Berlin called for a general strike. Kaiser Wilhelm II, an absurd and incompetent militarist, at last faced the truth that his time was up and abdicated the throne, leaving confusion in his wake. On November 9, Philipp Scheidemann, a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP), seized the moment to declare the founding of a new republic.

It was slightly more than a century ago, in November 1918, that revolution swept through Germany, bringing chaos to a country that, in the final days of World War I, was already in desperate straits and verging on collapse. Although it was obvious to nearly everyone that the war was lost, the fighting staggered on, even as a growing pacifist movement issued the cry for “Peace, Freedom, Bread!” In Kiel on the Baltic Sea, sailors at the docks refused the order for a last battle and went into open mutiny, while soldiers and revolutionary workers in Berlin called for a general strike. Kaiser Wilhelm II, an absurd and incompetent militarist, at last faced the truth that his time was up and abdicated the throne, leaving confusion in his wake. On November 9, Philipp Scheidemann, a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP), seized the moment to declare the founding of a new republic. Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the

Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the

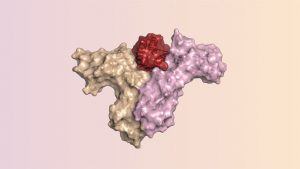

For patients with aggressive kidney and skin cancers, an immune-boosting protein called interleukin-2 (IL-2) can be a lifesaver. But the dose at which it fights cancer can also produce life-threatening side effects. Now, scientists have used computer modeling to design a new protein from scratch that mimics IL-2’s immune-enhancing abilities, while avoiding its dangerous side effects. The protein has so far been tested only in animals, but it may soon enter human trials. IL-2 plays a key role in directing the body’s immune response to outside invaders. The protein, a signaling molecule called a cytokine, ramps up the activity of white blood cells known as T lymphocytes by binding simultaneously to their IL-2β and IL-2γ receptors. In cells where a third type of receptor, IL-2α, is present, IL-2 binds collectively to all three. In other white blood cells, this dampens the body’s immune response. But it can also occur in cells in blood vessels, causing those vessels to leak, a potentially deadly condition.

For patients with aggressive kidney and skin cancers, an immune-boosting protein called interleukin-2 (IL-2) can be a lifesaver. But the dose at which it fights cancer can also produce life-threatening side effects. Now, scientists have used computer modeling to design a new protein from scratch that mimics IL-2’s immune-enhancing abilities, while avoiding its dangerous side effects. The protein has so far been tested only in animals, but it may soon enter human trials. IL-2 plays a key role in directing the body’s immune response to outside invaders. The protein, a signaling molecule called a cytokine, ramps up the activity of white blood cells known as T lymphocytes by binding simultaneously to their IL-2β and IL-2γ receptors. In cells where a third type of receptor, IL-2α, is present, IL-2 binds collectively to all three. In other white blood cells, this dampens the body’s immune response. But it can also occur in cells in blood vessels, causing those vessels to leak, a potentially deadly condition. The testament Dostoevsky left his children was the parable of the Prodigal Son. He asked that it be read to them the night of the day he knew would be his last, and the late, great Joseph Frank judged that Dostoevsky had probably understood the whole of his life and all of his literature as having existed under the sign of this tale of “transgression, forgiveness, and redemption.”

The testament Dostoevsky left his children was the parable of the Prodigal Son. He asked that it be read to them the night of the day he knew would be his last, and the late, great Joseph Frank judged that Dostoevsky had probably understood the whole of his life and all of his literature as having existed under the sign of this tale of “transgression, forgiveness, and redemption.” Donald Trump campaigned on the absurd lie that the United States could construct a large concrete wall across the entire US-Mexico border and coerce the Mexican government into paying for its construction. The government is currently shut down because Trump refuses to admit that his absurd lie was, in fact, an absurd lie.

Donald Trump campaigned on the absurd lie that the United States could construct a large concrete wall across the entire US-Mexico border and coerce the Mexican government into paying for its construction. The government is currently shut down because Trump refuses to admit that his absurd lie was, in fact, an absurd lie. Thomas Piketty and his colleagues

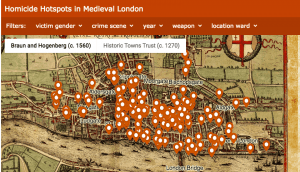

Thomas Piketty and his colleagues In July of 1316, a priest with a hankering for fresh apples sneaked into a walled garden in the Cripplegate area of London to help himself to the fruits therein. The gardener caught him in the act, and the priest brutally stabbed him to death with a knife—hardly godly behavior, but this was the Middle Ages. A religious occupation was no guarantee of moral standing.

In July of 1316, a priest with a hankering for fresh apples sneaked into a walled garden in the Cripplegate area of London to help himself to the fruits therein. The gardener caught him in the act, and the priest brutally stabbed him to death with a knife—hardly godly behavior, but this was the Middle Ages. A religious occupation was no guarantee of moral standing. Forward-thinking companies strive to be socially responsible. Beer commercials exhort us to drink responsibly. And every parent wants their kid to be more responsible. All in all, responsibility is a good thing, right? It is, until it’s not. What to do when you have too much of a good thing? This week, Savvy Psychologist Dr. Ellen Hendriksen offers four signs of over-responsibility, plus three ways to overcome it. Being a responsible person is usually a good thing—it means you’re committed, dependable, accountable, and care about others. It’s the opposite of shirking responsibility by pointing fingers or making excuses. But it’s easy to go too far. Do you take on everyone’s tasks? If someone you love is grumpy, do you assume it’s something you did? Do you apologize when someone bumps into you? Owning what’s yours—mistakes and blunders included—is a sign of maturity, but owning everybody else’s mistakes and blunders, not to mention tasks, duties, and emotions, is a sign of over-responsibility.

Forward-thinking companies strive to be socially responsible. Beer commercials exhort us to drink responsibly. And every parent wants their kid to be more responsible. All in all, responsibility is a good thing, right? It is, until it’s not. What to do when you have too much of a good thing? This week, Savvy Psychologist Dr. Ellen Hendriksen offers four signs of over-responsibility, plus three ways to overcome it. Being a responsible person is usually a good thing—it means you’re committed, dependable, accountable, and care about others. It’s the opposite of shirking responsibility by pointing fingers or making excuses. But it’s easy to go too far. Do you take on everyone’s tasks? If someone you love is grumpy, do you assume it’s something you did? Do you apologize when someone bumps into you? Owning what’s yours—mistakes and blunders included—is a sign of maturity, but owning everybody else’s mistakes and blunders, not to mention tasks, duties, and emotions, is a sign of over-responsibility. In the animal world, monogamy has some clear perks. Living in pairs can give animals some stability and certainty in the constant struggle to reproduce and protect their young—which may be why it has evolved independently in various species. Now, an analysis of gene activity within the brains of frogs, rodents, fish, and birds suggests there may be a pattern common to monogamous creatures. Despite very different brain structures and evolutionary histories, these animals all seem to have developed monogamy by turning on and off some of the same sets of genes. “It is quite surprising,” says Harvard University evolutionary biologist Hopi Hoekstra, who was not involved in the new work. “It suggests that there’s a sort of genomic strategy to becoming monogamous that evolution has repeatedly tapped into.” Evolutionary biologists have proposed various

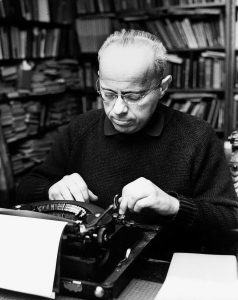

In the animal world, monogamy has some clear perks. Living in pairs can give animals some stability and certainty in the constant struggle to reproduce and protect their young—which may be why it has evolved independently in various species. Now, an analysis of gene activity within the brains of frogs, rodents, fish, and birds suggests there may be a pattern common to monogamous creatures. Despite very different brain structures and evolutionary histories, these animals all seem to have developed monogamy by turning on and off some of the same sets of genes. “It is quite surprising,” says Harvard University evolutionary biologist Hopi Hoekstra, who was not involved in the new work. “It suggests that there’s a sort of genomic strategy to becoming monogamous that evolution has repeatedly tapped into.” Evolutionary biologists have proposed various  The science-fiction writer and futurist Stanisław Lem was well acquainted with the way that fictional worlds can sometimes encroach upon reality. In his autobiographical essay “

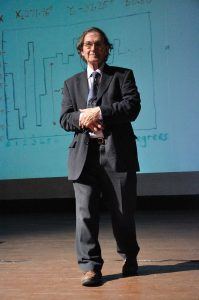

The science-fiction writer and futurist Stanisław Lem was well acquainted with the way that fictional worlds can sometimes encroach upon reality. In his autobiographical essay “ Sir Roger Penrose has had a remarkable life. He has contributed an enormous amount to our understanding of general relativity, perhaps more than anyone since Einstein himself — Penrose diagrams, singularity theorems, the Penrose process, cosmic censorship, and the list goes on. He has made important contributions to mathematics, including such fun ideas as the Penrose triangle and aperiodic tilings. He has also made bold conjectures in the notoriously contentious areas of quantum mechanics and the study of consciousness. In his spare time he’s managed to become an extremely successful author, writing such books as The Emperor’s New Mind and The Road to Reality. With far too much that we could have talked about, we decided to concentrate in this discussion on spacetime, black holes, and cosmology, but we made sure to reserve some time to dig into quantum mechanics and the brain by the end.

Sir Roger Penrose has had a remarkable life. He has contributed an enormous amount to our understanding of general relativity, perhaps more than anyone since Einstein himself — Penrose diagrams, singularity theorems, the Penrose process, cosmic censorship, and the list goes on. He has made important contributions to mathematics, including such fun ideas as the Penrose triangle and aperiodic tilings. He has also made bold conjectures in the notoriously contentious areas of quantum mechanics and the study of consciousness. In his spare time he’s managed to become an extremely successful author, writing such books as The Emperor’s New Mind and The Road to Reality. With far too much that we could have talked about, we decided to concentrate in this discussion on spacetime, black holes, and cosmology, but we made sure to reserve some time to dig into quantum mechanics and the brain by the end.