Yaneer Bar-Yam in Student Voices:

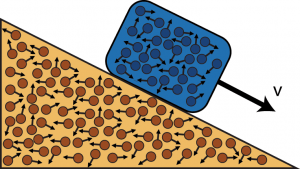

One of the hardest things to explain is why complex systems are actually different from simple systems. The problem is rooted in a set of ideas that work together and reinforce each other so that they appear seamless: Given a set of properties that a system has, we can study those properties with experiments and model what those properties do over time. Everything that is needed should be found in the data and the model we write down. The flaw in this seemingly obvious statement is that what is missing is realizing that one may be starting from the wrong properties. One might have missed one of the key properties that we need to include, or the set of properties that one has to describe might change over time. Then why don’t we add more properties until we include enough? The problem is that we will be overwhelmed by too many of them, the process never ends. The key, it turns out, is figuring out how to identify which properties are important, which itself is a dynamic property of the system.

One of the hardest things to explain is why complex systems are actually different from simple systems. The problem is rooted in a set of ideas that work together and reinforce each other so that they appear seamless: Given a set of properties that a system has, we can study those properties with experiments and model what those properties do over time. Everything that is needed should be found in the data and the model we write down. The flaw in this seemingly obvious statement is that what is missing is realizing that one may be starting from the wrong properties. One might have missed one of the key properties that we need to include, or the set of properties that one has to describe might change over time. Then why don’t we add more properties until we include enough? The problem is that we will be overwhelmed by too many of them, the process never ends. The key, it turns out, is figuring out how to identify which properties are important, which itself is a dynamic property of the system.

To explain this idea we can start from a review of the way this problem came up in physics and how it was solved for that case. The ideas are rooted in an approximation called “separation of scales.”

More here. [Thanks to Ali Minai. And, yes, I know this article is from 2017.]

In

In  What does the life of an Ottoman-born ethnic Armenian oil tycoon have to teach us about the modern world? Quite a lot, it turns out, judging by this fascinating biography of

What does the life of an Ottoman-born ethnic Armenian oil tycoon have to teach us about the modern world? Quite a lot, it turns out, judging by this fascinating biography of  It was the closest that physicist Pablo Jarillo-Herrero had ever come to being a rock star. When he stood up in March to give a talk in Los Angeles, California, he saw scientists packed into every nook of the meeting room. The organizers of the American Physical Society conference had to stream the session to a huge adjacent space, where a standing-room-only crowd had gathered. “I knew we had something very important,” he says, “but that was pretty crazy.”

It was the closest that physicist Pablo Jarillo-Herrero had ever come to being a rock star. When he stood up in March to give a talk in Los Angeles, California, he saw scientists packed into every nook of the meeting room. The organizers of the American Physical Society conference had to stream the session to a huge adjacent space, where a standing-room-only crowd had gathered. “I knew we had something very important,” he says, “but that was pretty crazy.” Is there any way to intervene usefully or meaningfully in public debate, in what the extremely online Twitter users are with gleeful irony calling the ‘discourse’ of the present moment?

Is there any way to intervene usefully or meaningfully in public debate, in what the extremely online Twitter users are with gleeful irony calling the ‘discourse’ of the present moment? As the West becomes

As the West becomes

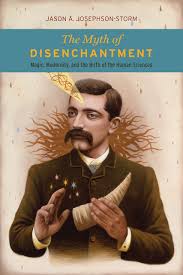

To catch up those who are unfamiliar with my book, The Myth of Disenchantment is rooted in the following observation: Many theorists have argued that what makes the modern world “modern” is that people no longer believe in spirits, myth, or magic — in this sense we are “disenchanted.” However, every day new proof arises that “modern” thinkers do in fact believe in magic and in spirits, and they have done so throughout history. According to a range of anthropological and sociological evidence, which I discuss in the book, the majority of people living in Europe and North America believe (to varying degrees) in the following: spirits, witches, psychical powers, magic, astrology, and demons. Scholars have known this was true of much of the rest of the globe, but have overlooked its continued presence in the West.

To catch up those who are unfamiliar with my book, The Myth of Disenchantment is rooted in the following observation: Many theorists have argued that what makes the modern world “modern” is that people no longer believe in spirits, myth, or magic — in this sense we are “disenchanted.” However, every day new proof arises that “modern” thinkers do in fact believe in magic and in spirits, and they have done so throughout history. According to a range of anthropological and sociological evidence, which I discuss in the book, the majority of people living in Europe and North America believe (to varying degrees) in the following: spirits, witches, psychical powers, magic, astrology, and demons. Scholars have known this was true of much of the rest of the globe, but have overlooked its continued presence in the West. None of this information is secret. But neither museums nor their trustees spell it out, so it’s hidden just enough that our collective delusions about museums can persist. The cover is only blown in extreme cases—tear-gassed kids—and it throws into the ugliest light one of the few public places of respite from our punishing society. It’s a particularly stark reminder that no organization is purely good when money is the major organizing principle. The art and search for meaning that constitute the best expression of humanity will always be diluted here. In this case it’s cut by the worst expression of humanity, war.

None of this information is secret. But neither museums nor their trustees spell it out, so it’s hidden just enough that our collective delusions about museums can persist. The cover is only blown in extreme cases—tear-gassed kids—and it throws into the ugliest light one of the few public places of respite from our punishing society. It’s a particularly stark reminder that no organization is purely good when money is the major organizing principle. The art and search for meaning that constitute the best expression of humanity will always be diluted here. In this case it’s cut by the worst expression of humanity, war. Quit

Quit Consider almost everything you know about heart disease, particularly the garden-variety type involving high cholesterol levels, clogged coronary arteries, stents and bypass surgeries. Now I want you to rebrand all that as “male-pattern” cardiovascular disease. That’s how some researchers are reframing it after taking a closer look at heart disease in women. For years cardiologists were baffled as to why up to half of women with classic symptoms of blocked vessels—chest pain, shortness of breath and an abnormal cardiac stress test—turn out to have open arteries. Doctors called it “cardiac syndrome X.” They didn’t understand it, and many women were subjected to repeated angiograms in search of blockages that weren’t there. That still happens today, but more doctors now recognize that despite having open arteries, about half of women with this pattern nonetheless have ischemia—poor blood flow through the heart. The condition has gained a mouthful of a name: ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease, or INOCA.

Consider almost everything you know about heart disease, particularly the garden-variety type involving high cholesterol levels, clogged coronary arteries, stents and bypass surgeries. Now I want you to rebrand all that as “male-pattern” cardiovascular disease. That’s how some researchers are reframing it after taking a closer look at heart disease in women. For years cardiologists were baffled as to why up to half of women with classic symptoms of blocked vessels—chest pain, shortness of breath and an abnormal cardiac stress test—turn out to have open arteries. Doctors called it “cardiac syndrome X.” They didn’t understand it, and many women were subjected to repeated angiograms in search of blockages that weren’t there. That still happens today, but more doctors now recognize that despite having open arteries, about half of women with this pattern nonetheless have ischemia—poor blood flow through the heart. The condition has gained a mouthful of a name: ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease, or INOCA. In 1909 five men converged on Clark University in Massachusetts to conquer the New World with an idea. At the head of this little troupe was psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. Ten years earlier Freud had introduced a new treatment for what was called “hysteria” in his book The Interpretation of Dreams. This work also introduced a scandalous view of the human psyche: underneath the surface of consciousness roils a largely inaccessible cauldron of deeply rooted drives, especially of sexual energy (the libido). These drives, held in check by socially inculcated morality, vent themselves in slips of the tongue, dreams and neuroses. The slips in turn provide evidence of the unconscious mind. At the invitation of psychologist G. Stanley Hall, Freud delivered five lectures at Clark. In the audience was philosopher William James, who had traveled from Harvard University to meet Freud. It is said that, as James departed, he told Freud, “The future of psychology belongs to your work.” And he was right.

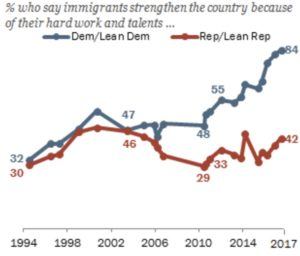

In 1909 five men converged on Clark University in Massachusetts to conquer the New World with an idea. At the head of this little troupe was psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. Ten years earlier Freud had introduced a new treatment for what was called “hysteria” in his book The Interpretation of Dreams. This work also introduced a scandalous view of the human psyche: underneath the surface of consciousness roils a largely inaccessible cauldron of deeply rooted drives, especially of sexual energy (the libido). These drives, held in check by socially inculcated morality, vent themselves in slips of the tongue, dreams and neuroses. The slips in turn provide evidence of the unconscious mind. At the invitation of psychologist G. Stanley Hall, Freud delivered five lectures at Clark. In the audience was philosopher William James, who had traveled from Harvard University to meet Freud. It is said that, as James departed, he told Freud, “The future of psychology belongs to your work.” And he was right. Whether you are an optimist or a pessimist is not just a question of personal temperament. It is also, increasingly, a question of politics. The divide between the optimists and the pessimists is as acute as any in contemporary politics and like many others—the generational divide between old and young, the educational divide between people who did and didn’t go to college—it cuts across left and right. There are left pessimists and right pessimists; left optimists and right optimists. What there isn’t is much common ground between them. Competing views about whether the world is getting better or worse has become another dialogue of the deaf.

Whether you are an optimist or a pessimist is not just a question of personal temperament. It is also, increasingly, a question of politics. The divide between the optimists and the pessimists is as acute as any in contemporary politics and like many others—the generational divide between old and young, the educational divide between people who did and didn’t go to college—it cuts across left and right. There are left pessimists and right pessimists; left optimists and right optimists. What there isn’t is much common ground between them. Competing views about whether the world is getting better or worse has become another dialogue of the deaf.

Nowhere else in the world did the year 1984 fulfill its apocalyptic portents as it did in India. Separatist violence in the Punjab, the military attack on the great Sikh temple of Amritsar; the assassination of the Prime Minister, Mrs Indira Gandhi; riots in several cities; the gas disaster in Bhopal – the events followed relentlessly on each other. There were days in 1984 when it took courage to open the New Delhi papers in the morning.

Nowhere else in the world did the year 1984 fulfill its apocalyptic portents as it did in India. Separatist violence in the Punjab, the military attack on the great Sikh temple of Amritsar; the assassination of the Prime Minister, Mrs Indira Gandhi; riots in several cities; the gas disaster in Bhopal – the events followed relentlessly on each other. There were days in 1984 when it took courage to open the New Delhi papers in the morning.