Sarah Scoles in The New York Times:

At first it was just one flower, but Emmanuel Mendoza, an undergraduate student at Texas A&M University, had worked hard to help it bloom. When this five-petaled thing burst forth from his English pea plant collection in late October, and then more flowers and even pea pods followed, he could also see, a little better, the future it might foretell on another world millions of miles from Earth. These weren’t just any pea plants. Some were grown in soil meant to mimic Mars’s inhospitable regolith, the mixture of grainy, eroded rocks and minerals that covers the planet’s surface. To that simulated regolith, Mr. Mendoza had added fertilizer called frass — the waste left after black soldier fly larvae are finished eating and digesting. Essentially, bug manure.

At first it was just one flower, but Emmanuel Mendoza, an undergraduate student at Texas A&M University, had worked hard to help it bloom. When this five-petaled thing burst forth from his English pea plant collection in late October, and then more flowers and even pea pods followed, he could also see, a little better, the future it might foretell on another world millions of miles from Earth. These weren’t just any pea plants. Some were grown in soil meant to mimic Mars’s inhospitable regolith, the mixture of grainy, eroded rocks and minerals that covers the planet’s surface. To that simulated regolith, Mr. Mendoza had added fertilizer called frass — the waste left after black soldier fly larvae are finished eating and digesting. Essentially, bug manure.

The goal for Mr. Mendoza and his collaborators was to investigate whether frass and the bugs that created it might someday help astronauts grow food and manage waste on Mars. Black soldier fly larvae could consume astronauts’ organic waste and process it into frass, which could be used as fertilizer to coax plants out of alien soil. Humans could eat the plants, and even food made from the larvae, producing more waste for the cycle to continue. While that might not ultimately be the way astronauts grow food on Mars, they will have to grow food. “We can’t take everything with us,” said Lisa Carnell, director for NASA’s Biological and Physical Sciences Division.

More here.

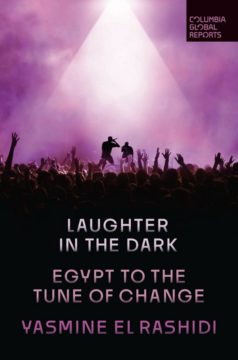

Mahraganat (which means “festivals” in Arabic) is made primarily by self-taught young men from lower-class backgrounds, whose songs are considered brash, even vulgar, because they rap and sing openly about their lives with seldom a trace of modesty. Egypt’s canonical singers and composers from the 20th century, particularly Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez, and Mohammed Abdel Wahab, possessed a virtuosic command of improvisational technique and classical repertoire. By comparison, mahraganat artists appeal first and foremost to friends from the block, weaving a unique lexicon of Arabic slang, boasts, insults, drug references, and sexual innuendo. The artists use Auto-Tune not only to add distortive, festive color to their rugged street anthems, but also for its manufacturer-intended purpose: to keep their voices in tune.

Mahraganat (which means “festivals” in Arabic) is made primarily by self-taught young men from lower-class backgrounds, whose songs are considered brash, even vulgar, because they rap and sing openly about their lives with seldom a trace of modesty. Egypt’s canonical singers and composers from the 20th century, particularly Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez, and Mohammed Abdel Wahab, possessed a virtuosic command of improvisational technique and classical repertoire. By comparison, mahraganat artists appeal first and foremost to friends from the block, weaving a unique lexicon of Arabic slang, boasts, insults, drug references, and sexual innuendo. The artists use Auto-Tune not only to add distortive, festive color to their rugged street anthems, but also for its manufacturer-intended purpose: to keep their voices in tune. Breaking down food requires coordination across dozens of cell types and many tissues — from muscle cells and immune cells to blood and lymphatic vessels. Heading this effort is the gut’s very own network of nerve cells, known as the enteric nervous system, which weaves through the intestinal walls from the esophagus down to the rectum. This network can function nearly independently from the brain; indeed, its complexity has earned it the nickname “the second brain.” And just like the brain, it’s made up of two kinds of nervous system cells: neurons and glia.

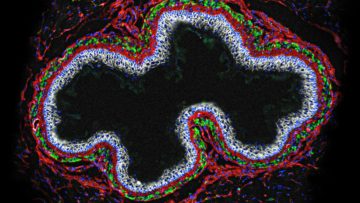

Breaking down food requires coordination across dozens of cell types and many tissues — from muscle cells and immune cells to blood and lymphatic vessels. Heading this effort is the gut’s very own network of nerve cells, known as the enteric nervous system, which weaves through the intestinal walls from the esophagus down to the rectum. This network can function nearly independently from the brain; indeed, its complexity has earned it the nickname “the second brain.” And just like the brain, it’s made up of two kinds of nervous system cells: neurons and glia.

In 2016,

In 2016,

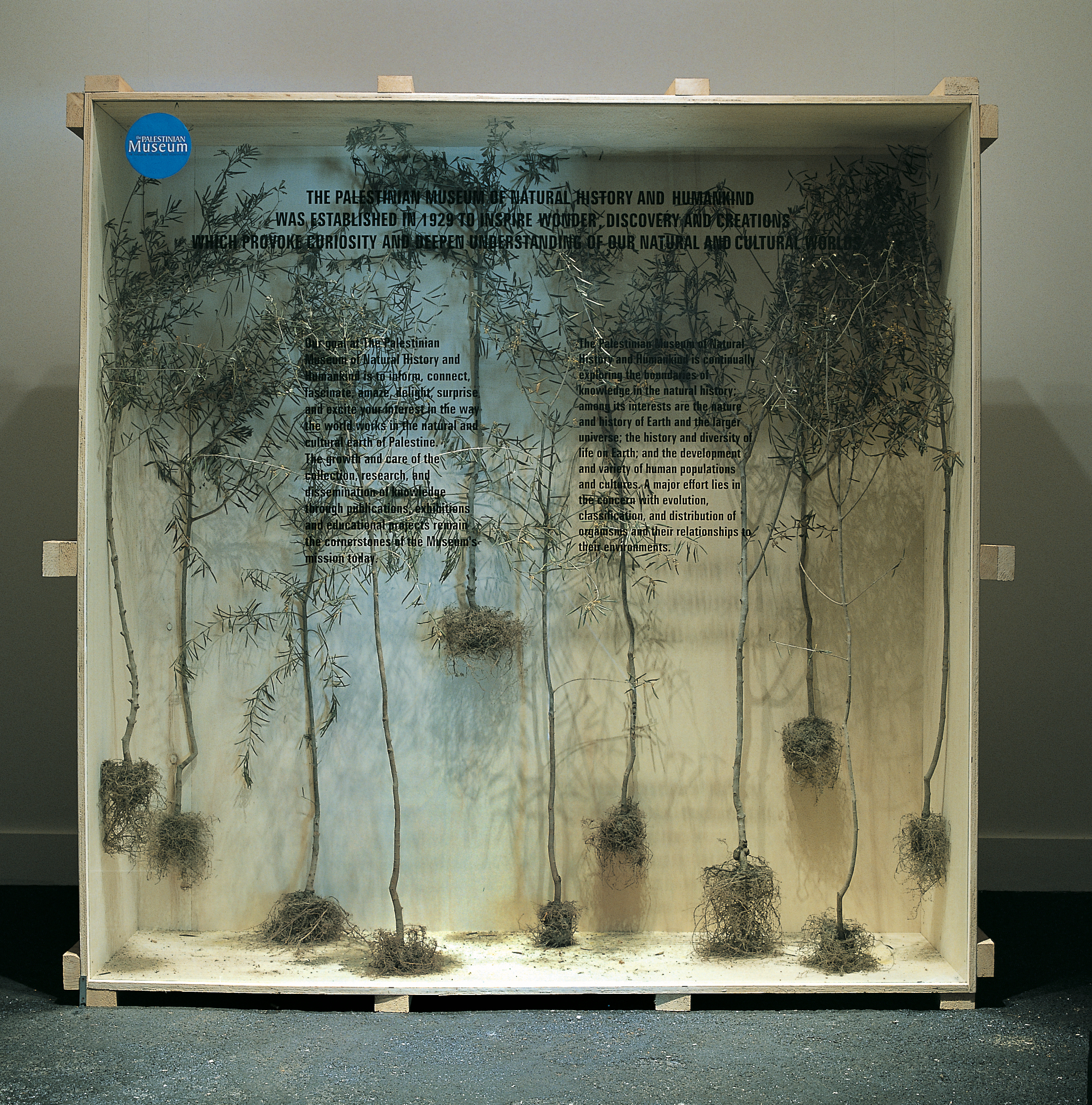

Khalil Rabah. About The Museum, 2004.

Khalil Rabah. About The Museum, 2004.

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?

Twenty-five years ago, the burgeoning science of consciousness studies was rife with promise. With cutting-edge neuroimaging tools leading to new research programmes, the neuroscientist Christof Koch was so optimistic, he bet a case of wine that we’d uncover its secrets by now. The philosopher David Chalmers had serious doubts, because consciousness research is, to put it mildly, difficult. Even what Chalmers called the easy problem of consciousness is hard, and that’s what the bet was about – whether we would uncover the neural structures involved in conscious experience. So, he took

Twenty-five years ago, the burgeoning science of consciousness studies was rife with promise. With cutting-edge neuroimaging tools leading to new research programmes, the neuroscientist Christof Koch was so optimistic, he bet a case of wine that we’d uncover its secrets by now. The philosopher David Chalmers had serious doubts, because consciousness research is, to put it mildly, difficult. Even what Chalmers called the easy problem of consciousness is hard, and that’s what the bet was about – whether we would uncover the neural structures involved in conscious experience. So, he took  The basic issue is that people hear the phrase “quantum mechanics,” or even take a course in it, and come away with the impression that reality is somehow pixelized — made up of smallest possible units — rather than being ultimately smooth and continuous. That’s not right! Quantum theory, as far as it is currently understood, is all about smoothness. The lumpiness of “quanta” is just apparent, although it’s a very important appearance.

The basic issue is that people hear the phrase “quantum mechanics,” or even take a course in it, and come away with the impression that reality is somehow pixelized — made up of smallest possible units — rather than being ultimately smooth and continuous. That’s not right! Quantum theory, as far as it is currently understood, is all about smoothness. The lumpiness of “quanta” is just apparent, although it’s a very important appearance. O

O