Sudden Sketch Poem

Gary’s sink has a shroud burlap

the rub brush tinware plout

leans on right side

like a red woman’s hair

the faucet leaks little lovedrops

The teacup’s upsidedown with visions

of green mountains and brown lousy

Chinese mysterious up heights

The frying pan’s still wet

The spoon’s by two petals of flower

The washrag’s hung on edge like bloomers

I don’t know what to say

about the dishpan, the soap

The sink itself inside or what

is hidden underneath the bomb burlap

Shroudflap except two onions

And an orange and old wheat germ.

Wheat meal. The hoodlatch heliograph

With the cross that makes the devil

Hiss, ah, the upper coral sensen soups

And fast condiments, curries, rices,

Roaches, reels, tin, tip, plastickets,

Toothbrushes and armies, and armies

of insulated schiller, squozen gumbrop

Peste pans, light of marin, pirshar,

Magic dancing lights of gray and white

And all for verse I wrote it.

by Jack Kerouac

April 1956, McCorkle’s Shack

from Kerouac- Poems All Sizes

City Light Books, 1992

Things in Gaza have been in constant deterioration. Every single day that passes, new crises are compounded over the crises that already exist. It’s been over 40 days of non-stop bombardment. I’ve been saying many times throughout my coverage that what we have seen in this war, what we are witnessing is unlike any other war in any other place that anyone else has witnessed or lived through. The bombardments of hospitals, of UNRWA schools, residential homes—there’s no place that is not under fire. There’s no place that is not targeted from day one.

Things in Gaza have been in constant deterioration. Every single day that passes, new crises are compounded over the crises that already exist. It’s been over 40 days of non-stop bombardment. I’ve been saying many times throughout my coverage that what we have seen in this war, what we are witnessing is unlike any other war in any other place that anyone else has witnessed or lived through. The bombardments of hospitals, of UNRWA schools, residential homes—there’s no place that is not under fire. There’s no place that is not targeted from day one. It is difficult to predict when one will spend the night at a hotel in Newark, let alone three, and uncommon to agree to such a scenario willingly. If you live there already, you stay home. If you’re there for a professional engagement, your boss made you go. If your flight has been canceled, you go there as a last resort. Whereas, though I felt compelled to be there, I couldn’t point to an authority outside of myself that had forced my hand. The room had been booked a week in advance.

It is difficult to predict when one will spend the night at a hotel in Newark, let alone three, and uncommon to agree to such a scenario willingly. If you live there already, you stay home. If you’re there for a professional engagement, your boss made you go. If your flight has been canceled, you go there as a last resort. Whereas, though I felt compelled to be there, I couldn’t point to an authority outside of myself that had forced my hand. The room had been booked a week in advance.

Is it appropriate to call the three members of the sketch comedy group Please Don’t Destroy “boys”? They are grown men, in a sense, with jobs (Saturday Night Live writers) and, one assumes, growing 401(k)s. They’re in their mid-to-late 20s, six years into a career that started at New York University. Yet in other ways they are very obviously still tweens, gangly and silly, still figuring it all out. They’ve been known to sign emails to reporters “The Boys.” (This was revealed in

Is it appropriate to call the three members of the sketch comedy group Please Don’t Destroy “boys”? They are grown men, in a sense, with jobs (Saturday Night Live writers) and, one assumes, growing 401(k)s. They’re in their mid-to-late 20s, six years into a career that started at New York University. Yet in other ways they are very obviously still tweens, gangly and silly, still figuring it all out. They’ve been known to sign emails to reporters “The Boys.” (This was revealed in  “T

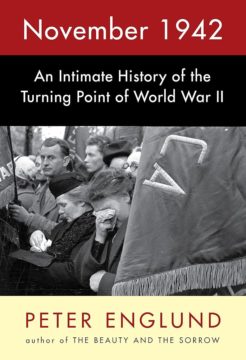

“T This format ensures an extraordinary — and bewildering — range of striking details. We learn that the bloated bodies of those who died in German U-boat attacks wash up along the coastline of Savannah, Ga.; that at the Treblinka death camp “there is almost always a jam when the door of one of the gas chambers is opened,” as the limbs of the corpses are so densely entangled; that when British soldiers in North Africa take five Italian prisoners, one of them happens to be a tenor from the Milan opera, and all five sing as they help with breakfast; that a Chinese civil servant tasked by the Nationalist government with collecting taxes from the starving population of Henan reports that people are eating bark and grass and selling their children for steamed rolls; that U.S. troops at Guadalcanal, desperate for alcohol of any kind, drink after-shave lotion “filtered through bread”; and that when a private with the Red Army northwest of Stalingrad peers out from his trench one night, he discovers a scene of terrible and staggering beauty — a freezing rain, reflecting the full moon’s light, has formed a shimmering veil over the landscape and the corpses of his dead companions.

This format ensures an extraordinary — and bewildering — range of striking details. We learn that the bloated bodies of those who died in German U-boat attacks wash up along the coastline of Savannah, Ga.; that at the Treblinka death camp “there is almost always a jam when the door of one of the gas chambers is opened,” as the limbs of the corpses are so densely entangled; that when British soldiers in North Africa take five Italian prisoners, one of them happens to be a tenor from the Milan opera, and all five sing as they help with breakfast; that a Chinese civil servant tasked by the Nationalist government with collecting taxes from the starving population of Henan reports that people are eating bark and grass and selling their children for steamed rolls; that U.S. troops at Guadalcanal, desperate for alcohol of any kind, drink after-shave lotion “filtered through bread”; and that when a private with the Red Army northwest of Stalingrad peers out from his trench one night, he discovers a scene of terrible and staggering beauty — a freezing rain, reflecting the full moon’s light, has formed a shimmering veil over the landscape and the corpses of his dead companions.

Charlotte Kent (Rail): Photography often gets discussed in terms of its stillness, of capturing or freezing a moment. But, in Where I Find Myself (2018) you wrote about watching Robert Frank and discovering photography’s motion: “that was at the heart of what I had seen: movements, the physicality of it, the timing, the positioning. I played third base, I knew about that kind of movement, it was energy in the service of the moment.” Can you describe how photography was about movement and this physicality? And then maybe also, how baseball comes into that?

Charlotte Kent (Rail): Photography often gets discussed in terms of its stillness, of capturing or freezing a moment. But, in Where I Find Myself (2018) you wrote about watching Robert Frank and discovering photography’s motion: “that was at the heart of what I had seen: movements, the physicality of it, the timing, the positioning. I played third base, I knew about that kind of movement, it was energy in the service of the moment.” Can you describe how photography was about movement and this physicality? And then maybe also, how baseball comes into that?