by Timothy Don

The current economic crisis is crushing artists, museums, and galleries everywhere. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, an exorbitant rental market made maintaining a practice difficult before this crisis hit. It’s even harder now. With 3QD’s permission, I’m going to use this column to talk about the work of some of the artists and art professionals I have met here. I ask you to support artists wherever and however you can.

Peter de Swart, works on paper: Triptych

The triptych form is associated with religious painting. It first appeared as a feature of early Christian art and became popular for altar paintings and devotionals during the Middle Ages. While Peter de Swart’s Triptych is not overtly religious, it emanates an undeniably religious or spiritual aura. It is, in a word, numinous. To encounter this painting is to witness a sacred transaction. You’d have to be a stone to look at it and not experience a yearning for the divine. Why, apart from its rearticulation of the history and symbolism of the triptych form, is that?

It must have something to do, first of all, with the simple purity of the object pictured, which appears to be a bowl of some sort. Bowls are one of those inventions (like scissors or chopsticks or the hourglass) that we got right the first time. They were perfect the moment they appeared. In the bowl, function lives harmoniously with form. Its shape is so ideal as to be almost Platonic. Furthermore, bowls are used to prepare and serve food and drink, which means that they give sustenance, enable shared meals, and consequently help to strengthen communal bonds and deepen human relationships. Finally, bowls are vessels. Like hands and pockets and ships, they hold and contain and convey things—but they are not grasping like hands, nor like pockets do they secret away their contents, and they don’t trade goods and gold like ships. Quite the opposite, in fact: Bowls are generous, open, gratuitous. They give away the things they hold.

All of these attributes (form, use value, ethos) lend bowls a quasi-spiritual redolence, but they do not make bowls sacred. If this triptych depicted a bowl no different from any other bowl, then its effect would be decorative rather than numinous. This bowl is special. Again we must ask: Why is that? Read more »

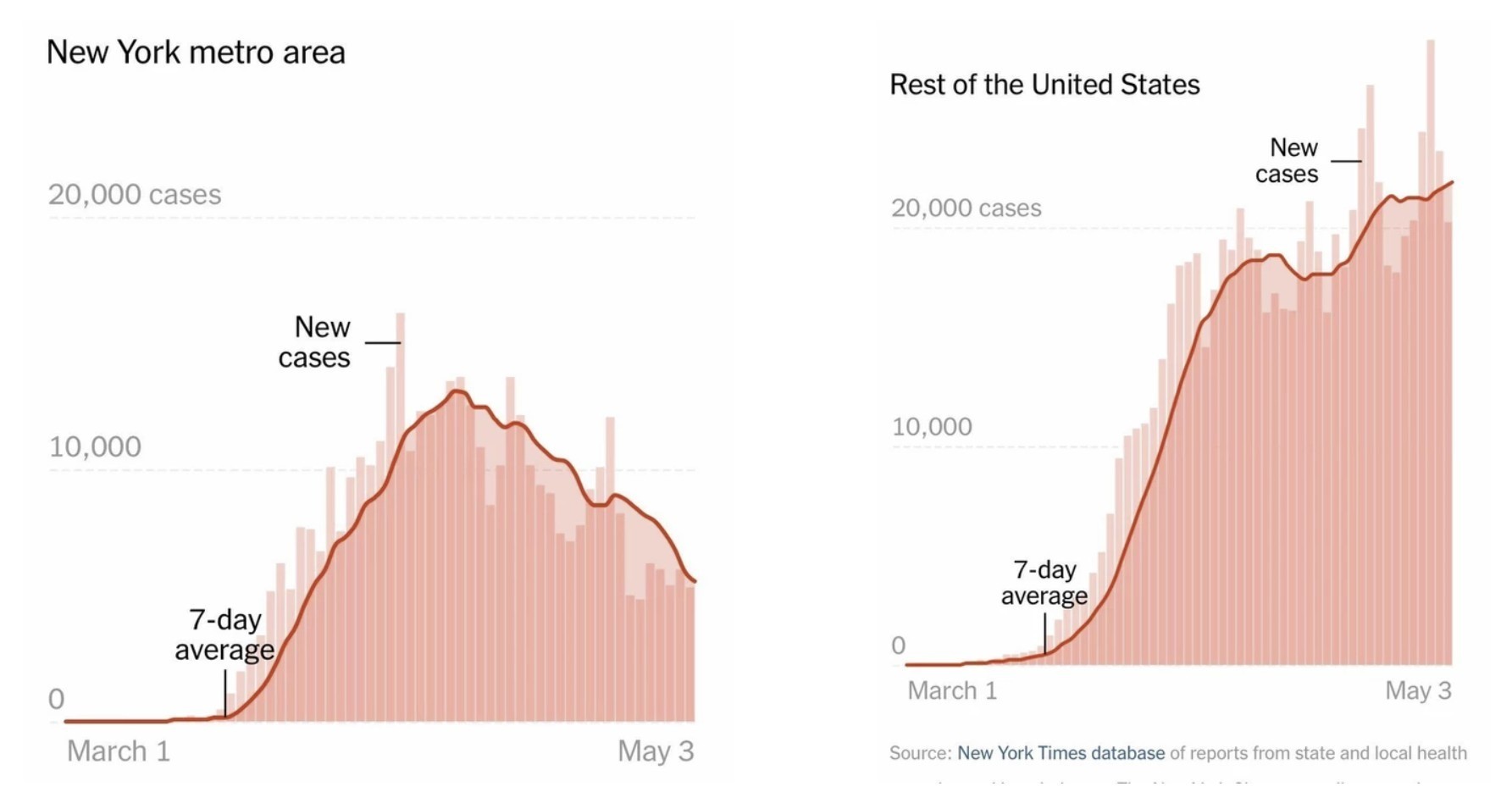

For a few fleeting moments during New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s daily coronavirus briefing on Wednesday, the somber grimace that has filled our screens for weeks was briefly replaced by something resembling a smile.

For a few fleeting moments during New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s daily coronavirus briefing on Wednesday, the somber grimace that has filled our screens for weeks was briefly replaced by something resembling a smile. Two thoughts have long come unbidden to my mind whenever I hear people talking about doing their family trees, or, more recently, getting their DNA done. The first is of Bruce Willis’s character in Pulp Fiction, the boxer Butch Coolidge in the back of the taxi, who, when asked by his South American driver what his name means, replies, “I’m an American, baby, our names don’t mean shit.” The other is of Seneca, who wrote in his Moral Letters to Lucilius: “If there is any good in philosophy, it is this, — that it never looks into pedigrees. All men, if traced back to their original source, spring from the gods.”

Two thoughts have long come unbidden to my mind whenever I hear people talking about doing their family trees, or, more recently, getting their DNA done. The first is of Bruce Willis’s character in Pulp Fiction, the boxer Butch Coolidge in the back of the taxi, who, when asked by his South American driver what his name means, replies, “I’m an American, baby, our names don’t mean shit.” The other is of Seneca, who wrote in his Moral Letters to Lucilius: “If there is any good in philosophy, it is this, — that it never looks into pedigrees. All men, if traced back to their original source, spring from the gods.”

In the dark days of quarantine, I have a habit, born of a fretful insomnia, of rising before dawn. Descending the stairs from my attic room, passing second-floor bedrooms, I imagine I am an all-knowing god of some small universe, like Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace, and can peer into the dreams of my loved ones.

In the dark days of quarantine, I have a habit, born of a fretful insomnia, of rising before dawn. Descending the stairs from my attic room, passing second-floor bedrooms, I imagine I am an all-knowing god of some small universe, like Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace, and can peer into the dreams of my loved ones. Twenty years ago, the US Department of Defense set out a clear warning: “Historians in the next millennium may find that the 20th century’s greatest fallacy was the belief that infectious diseases were nearing elimination. The resultant complacency has actually increased the threat.” Along with other western nations, federal and state governments in America had spent the previous decade or so dismantling public health programmes dealing with communicable diseases in order to concentrate funds on degenerative illnesses: diabetes, heart disease, cancer, stroke. Corporate investment in the development of new vaccines and antibiotics almost dried up, as if the battle that humans had waged over millennia against plague and pestilence had now been won – at least in the developed world. Michael Osterholm, the Minnesota state epidemiologist, informed US Congress in 1996: “I am here to bring you the sobering and unfortunate news that our ability to detect and monitor infectious disease threats to health in this country is in serious jeopardy. . . . For 12 of the states or territories, there is no one who is responsible for food or water-borne disease surveillance. You could sink the Titanic in their back yard and they would not know they had water.”

Twenty years ago, the US Department of Defense set out a clear warning: “Historians in the next millennium may find that the 20th century’s greatest fallacy was the belief that infectious diseases were nearing elimination. The resultant complacency has actually increased the threat.” Along with other western nations, federal and state governments in America had spent the previous decade or so dismantling public health programmes dealing with communicable diseases in order to concentrate funds on degenerative illnesses: diabetes, heart disease, cancer, stroke. Corporate investment in the development of new vaccines and antibiotics almost dried up, as if the battle that humans had waged over millennia against plague and pestilence had now been won – at least in the developed world. Michael Osterholm, the Minnesota state epidemiologist, informed US Congress in 1996: “I am here to bring you the sobering and unfortunate news that our ability to detect and monitor infectious disease threats to health in this country is in serious jeopardy. . . . For 12 of the states or territories, there is no one who is responsible for food or water-borne disease surveillance. You could sink the Titanic in their back yard and they would not know they had water.” In this half-life of quarantine, danger lurks in the unlikeliest of places: the touch of an elevator button, a store-bought carton of milk, my son’s sneeze. Insidious and cunning, death is everywhere around us.

In this half-life of quarantine, danger lurks in the unlikeliest of places: the touch of an elevator button, a store-bought carton of milk, my son’s sneeze. Insidious and cunning, death is everywhere around us. Stuart Jeffries in The Guardian:

Stuart Jeffries in The Guardian: Tyler Cowen interviews Adam Tooze over at Medium:

Tyler Cowen interviews Adam Tooze over at Medium:

Jonathan Fuller in Boston Review:

Jonathan Fuller in Boston Review: George Scialabba reviews Martha Nussbaum’s The Cosmopolitan Tradition: A Noble but Flawed Ideal in Inference:

George Scialabba reviews Martha Nussbaum’s The Cosmopolitan Tradition: A Noble but Flawed Ideal in Inference: “[W]hat we experience in our dreams … is as much a part of the overall economy of our soul as anything we ‘really’ experience.”

“[W]hat we experience in our dreams … is as much a part of the overall economy of our soul as anything we ‘really’ experience.” “The country Trump promised to make great again has never in its history seemed so pitiful,”

“The country Trump promised to make great again has never in its history seemed so pitiful,”