Month: May 2020

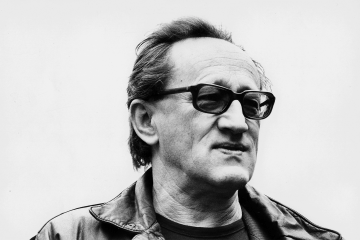

Heiner Müller—poet, playwright, and informant—embodied the divisions of postwar Germany

Holly Case at the Poetry Foundation:

“Unlike Lenin, Hitler came to power in a free election, which makes Auschwitz also the result of free elections.” The East German dramatist and poet Heiner Müller wrote these words in late November of 1989, on the eve of the first free elections on the territory of the German Democratic Republic (socialist East Germany) since 1932, when the Nazis came to power. Never one for feel-good moments, Müller’s thinking was deeply out of sync with the general euphoria that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall. While giving a speech on Berlin’s Alexanderplatz on November 4, 1989, he didn’t echo the sweeping optimism of the other speakers but read a statement calling for independent unions; many in the crowd booed him. In his autobiography, Müller admitted that the fall of the GDR had not been easy for him: “Suddenly there was no adversary…whoever no longer has an enemy will meet him in the mirror.”

“Unlike Lenin, Hitler came to power in a free election, which makes Auschwitz also the result of free elections.” The East German dramatist and poet Heiner Müller wrote these words in late November of 1989, on the eve of the first free elections on the territory of the German Democratic Republic (socialist East Germany) since 1932, when the Nazis came to power. Never one for feel-good moments, Müller’s thinking was deeply out of sync with the general euphoria that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall. While giving a speech on Berlin’s Alexanderplatz on November 4, 1989, he didn’t echo the sweeping optimism of the other speakers but read a statement calling for independent unions; many in the crowd booed him. In his autobiography, Müller admitted that the fall of the GDR had not been easy for him: “Suddenly there was no adversary…whoever no longer has an enemy will meet him in the mirror.”

That line proved prophetic. As he was dying of throat cancer in 1995, just a few years after assuming the directorship of Bertolt Brecht’s famous Berliner Ensemble theater, he expressed admiration for his fatal tumor.

More here.

Men

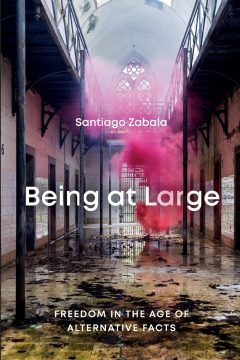

Hermeneutics and the Framing of “Truth”

William Egginton at the LARB:

This point goes to the heart of Zabala’s book, as well as to the mistaken concerns about the hermeneutic tradition he defends. To say, with Zabala, that “there is no ‘neutral observation language’ that can erase human differences,” and that “these differences are not the source of our problems but rather the only possible route to their provisional solution,” is not to embrace or give succor to those making power grabs using bald assertions of “alternative facts,” but the very opposite. It is to say that “facts, information, and data by themselves do nothing. ‘Facts remain robust,’ as [philosopher of science Bruno] Latour says, ‘only when they are supported by a common culture, by institutions that can be trusted, by a more or less decent public life, by more or less reliable media.’” Let’s be quick to douse the realist canard that is sure to arise at this point — that relativist arguments are self-negating since, if all statements of fact are subject to cultural, historical, and institutional contexts, then so is this one — by stating the obvious: of course Zabala’s (and my) positions are subject to the same frame-dependency as anyone else’s, but this is no more self-refuting or paradoxical than to say that all truth statements are made in a natural language that not everyone understands, including this one.

This point goes to the heart of Zabala’s book, as well as to the mistaken concerns about the hermeneutic tradition he defends. To say, with Zabala, that “there is no ‘neutral observation language’ that can erase human differences,” and that “these differences are not the source of our problems but rather the only possible route to their provisional solution,” is not to embrace or give succor to those making power grabs using bald assertions of “alternative facts,” but the very opposite. It is to say that “facts, information, and data by themselves do nothing. ‘Facts remain robust,’ as [philosopher of science Bruno] Latour says, ‘only when they are supported by a common culture, by institutions that can be trusted, by a more or less decent public life, by more or less reliable media.’” Let’s be quick to douse the realist canard that is sure to arise at this point — that relativist arguments are self-negating since, if all statements of fact are subject to cultural, historical, and institutional contexts, then so is this one — by stating the obvious: of course Zabala’s (and my) positions are subject to the same frame-dependency as anyone else’s, but this is no more self-refuting or paradoxical than to say that all truth statements are made in a natural language that not everyone understands, including this one.

more here.

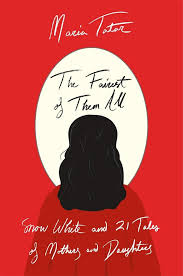

The Psyche of Snow White

Lucy Lethbridge at Literary Review:

In its different versions, the tale has several recurring elements, though not all of them are present in every case. The chief one is the jealousy that rages in a beautiful mother (or stepmother, or mother-in-law) for her even more beautiful daughter. Then there is the mirror (or sometimes the sun or the moon and, in one version, a trout in a deep well) that reflects back to the mother the truth about her own beauty being surpassed. Someone is sent to kill the girl in the forest, sometimes a huntsman but occasionally an old woman or a witch; beguiled by the child’s beauty, they set her free, returning to the mother with a bloodstained shirt or an animal’s entrails. Lost in the forest, the child often comes upon a house in which to shelter. It might be lived in by untidy dwarfs (this gave Disney an opportunity to make Snow White into a perfect 1930s housewife), but often its inhabitants are immaculately tidy dwarfs (as in the Grimms’ version), and occasionally they are gangs of robbers or even brothers who look upon Snow White as a sister to be protected. Sometimes there are seven of them in the house, sometimes twelve.

In its different versions, the tale has several recurring elements, though not all of them are present in every case. The chief one is the jealousy that rages in a beautiful mother (or stepmother, or mother-in-law) for her even more beautiful daughter. Then there is the mirror (or sometimes the sun or the moon and, in one version, a trout in a deep well) that reflects back to the mother the truth about her own beauty being surpassed. Someone is sent to kill the girl in the forest, sometimes a huntsman but occasionally an old woman or a witch; beguiled by the child’s beauty, they set her free, returning to the mother with a bloodstained shirt or an animal’s entrails. Lost in the forest, the child often comes upon a house in which to shelter. It might be lived in by untidy dwarfs (this gave Disney an opportunity to make Snow White into a perfect 1930s housewife), but often its inhabitants are immaculately tidy dwarfs (as in the Grimms’ version), and occasionally they are gangs of robbers or even brothers who look upon Snow White as a sister to be protected. Sometimes there are seven of them in the house, sometimes twelve.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Against Roses

A long eugenic past

reduces roses to

a vain and pampered caste.

Their charm is artifice,

their fragile shell of cells

unfit for wilderness.

Their languid symmetries

and anorexic airs

exalt deformities.

A run of blossoms, thick

and tangled by the road,

displays a truer pick.

Prefer the bindweed vines

that cannot stand alone

yet clench the mossy spines

of trees and grasp as tight

as nightmares or disease

while hoarding hints of light.

By cloning a delight,

obsessing towards some form,

we dull what should excite.

A rose bouquet contrives

to label wordless joy

when nothing true survives.

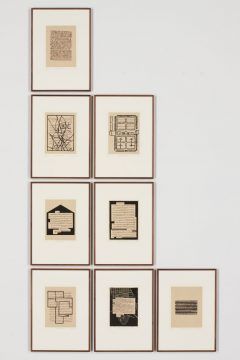

Zarina Hashmi, Artist of a World in Search of Home

Holland Cotter in The New York Times:

Ms. Hashmi, who preferred to identify herself professionally by only her first name, became internationally known for woodcuts and intaglio prints, many combining semiabstract images of houses and cities she had lived in accompanied by inscriptions written in Urdu, a language spoken primarily by Muslim South Asians. (It is the official national language of Pakistan.) In South Asia itself, she is particularly revered as a representative of a now-vanishing generation of artists who were alive during the 1947 partition of the subcontinent along ethnic and religious lines, a catastrophic event that, she felt, cut her loose from her roots and haunted her life and work. Zarina Rashid was born on July 16, 1937, the youngest of five children, in the small Indian town of Aligarh, where her father, Sheikh Abdur Rashid, taught at Aligarh Muslim University. Her mother, Fahmida Begum, was a homemaker. In her 2018 memoir, “Directions to My House,” Ms. Hashmi described growing up in what she called a traditional Muslim home. In hot months she and her older sister Rani would sleep outdoors “under the stars and plot our journeys in life.” The floor plan of her childhood house, whose walls enclosed a fragrant garden, became a recurrent presence in her art. That life abruptly ended with the partition of India and the violence between Muslims and Hindus. For safety, her father sent the family to Karachi in the newly formed Pakistan. The experience of fleeing to a refugee camp and seeing bodies left in the road stayed with Ms. Hashmi. “These memories formed how I think about a lot of things: fear, separation, migration, the people you know, or think you know,” she wrote in her memoir.

Ms. Hashmi, who preferred to identify herself professionally by only her first name, became internationally known for woodcuts and intaglio prints, many combining semiabstract images of houses and cities she had lived in accompanied by inscriptions written in Urdu, a language spoken primarily by Muslim South Asians. (It is the official national language of Pakistan.) In South Asia itself, she is particularly revered as a representative of a now-vanishing generation of artists who were alive during the 1947 partition of the subcontinent along ethnic and religious lines, a catastrophic event that, she felt, cut her loose from her roots and haunted her life and work. Zarina Rashid was born on July 16, 1937, the youngest of five children, in the small Indian town of Aligarh, where her father, Sheikh Abdur Rashid, taught at Aligarh Muslim University. Her mother, Fahmida Begum, was a homemaker. In her 2018 memoir, “Directions to My House,” Ms. Hashmi described growing up in what she called a traditional Muslim home. In hot months she and her older sister Rani would sleep outdoors “under the stars and plot our journeys in life.” The floor plan of her childhood house, whose walls enclosed a fragrant garden, became a recurrent presence in her art. That life abruptly ended with the partition of India and the violence between Muslims and Hindus. For safety, her father sent the family to Karachi in the newly formed Pakistan. The experience of fleeing to a refugee camp and seeing bodies left in the road stayed with Ms. Hashmi. “These memories formed how I think about a lot of things: fear, separation, migration, the people you know, or think you know,” she wrote in her memoir.

…Near-abstract images of houses recurred. A 1981 cast-paper relief called “Homecoming” is essentially an aerial view of a courtyard surrounded by arches, reminiscent of the one in her childhood home. A bronze sculpture, “I Went on a Journey III” (1991), is a miniature house on wheels. The prints in a portfolio called “Homes I Made/A Life in Nine Lines” are based on blueprints of houses that Ms. Hashmi had lived in from 1958 onward. And in a print series called “Letters From Home,” Ms. Hashmi overlaid images of both house and city onto the texts of letters, often about family deaths and loss, that her sister Rani had written to her but never sent. Significantly, each letter is transcribed in Urdu script, as are many identifying labels in other prints. Urdu is slowly going out of currency in sectarian India, but for Ms. Hashmi it defined “home” as surely as images of maps and houses did. “The biggest loss for me is language,” she told Ms. Stewart. “Specifically poetry. Before I go to bed lately, thanks to YouTube, I listen to the recitation of poetry in Urdu. I jokingly say I have lived a life in translation.”

More here.

Profile of a killer: the complex biology powering the coronavirus pandemic

David Cyranoski in Nature:

In 1912, German veterinarians puzzled over the case of a feverish cat with an enormously swollen belly. That is now thought to be the first reported example of the debilitating power of a coronavirus. Veterinarians didn’t know it at the time, but coronaviruses were also giving chickens bronchitis, and pigs an intestinal disease that killed almost every piglet under two weeks old. The link between these pathogens remained hidden until the 1960s, when researchers in the United Kingdom and the United States isolated two viruses with crown-like structures causing common colds in humans. Scientists soon noticed that the viruses identified in sick animals had the same bristly structure, studded with spiky protein protrusions. Under electron microscopes, these viruses resembled the solar corona, which led researchers in 1968 to coin the term coronaviruses for the entire group. It was a family of dynamic killers: dog coronaviruses could harm cats, the cat coronavirus could ravage pig intestines. Researchers thought that coronaviruses caused only mild symptoms in humans, until the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 revealed how easily these versatile viruses could kill people.

In 1912, German veterinarians puzzled over the case of a feverish cat with an enormously swollen belly. That is now thought to be the first reported example of the debilitating power of a coronavirus. Veterinarians didn’t know it at the time, but coronaviruses were also giving chickens bronchitis, and pigs an intestinal disease that killed almost every piglet under two weeks old. The link between these pathogens remained hidden until the 1960s, when researchers in the United Kingdom and the United States isolated two viruses with crown-like structures causing common colds in humans. Scientists soon noticed that the viruses identified in sick animals had the same bristly structure, studded with spiky protein protrusions. Under electron microscopes, these viruses resembled the solar corona, which led researchers in 1968 to coin the term coronaviruses for the entire group. It was a family of dynamic killers: dog coronaviruses could harm cats, the cat coronavirus could ravage pig intestines. Researchers thought that coronaviruses caused only mild symptoms in humans, until the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 revealed how easily these versatile viruses could kill people.

Now, as the death toll from the COVID-19 pandemic surges, researchers are scrambling to uncover as much as possible about the biology of the latest coronavirus, named SARS-CoV-2. A profile of the killer is already emerging. Scientists are learning that the virus has evolved an array of adaptations that make it much more lethal than the other coronaviruses humanity has met so far. Unlike close relatives, SARS-CoV-2 can readily attack human cells at multiple points, with the lungs and the throat being the main targets. Once inside the body, the virus makes use of a diverse arsenal of dangerous molecules. And genetic evidence suggests that it has been hiding out in nature possibly for decades. But there are many crucial unknowns about this virus, including how exactly it kills, whether it will evolve into something more — or less — lethal and what it can reveal about the next outbreak from the coronavirus family. “There will be more, either out there already or in the making,” says Andrew Rambaut, who studies viral evolution at the University of Edinburgh, UK.

More here.

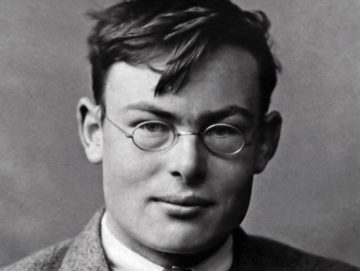

The extraordinary mind of Frank Ramsey

Alex Dean in Prospect:

Unless you have studied philosophy, maths or economics, it is unlikely you have heard of Frank Ramsey. And if you have, it is probably as a minor character in stories about his celebrated Cambridge philosophical contemporaries Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Unless you have studied philosophy, maths or economics, it is unlikely you have heard of Frank Ramsey. And if you have, it is probably as a minor character in stories about his celebrated Cambridge philosophical contemporaries Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

That’s a shame. Even as a teenager Ramsey displayed a genius to rival these figures. He was Wittgenstein’s favourite intellectual sparring partner. GE Moore revered him. AJ Ayer, meanwhile, once said it was a great pity that Cambridge philosophers spent the 1930s “chewing over Wittgenstein when they ought to have been chewing over Ramsey.” And he was revolutionary not only in philosophy and maths, but also economics: Keynes found Ramsey’s criticisms devastating and agonised over how to answer them. This is all the more remarkable given that Ramsey died at the age of 26 from a mystery liver ailment.

Today there are professorships bearing his name not only at Cambridge but also at Harvard; there is even a Frank Ramsey medal. Even so, he should occupy a much more prominent place in the story of modern philosophy. Despite the posthumous publication in 2012 of a memoir written by his sister, Margaret Paul, there has never been a comprehensive biography—until now. In her important new work, Cheryl Misak, of the University of Toronto, finally gives Ramsey the consideration he deserves. Misak has access to previously unaired interviews with family members shared with her by documentary-maker Laurie Kahn, who had planned to write a thesis on Ramsey while a student. Her project is both to truly render the life of this little-known thinker and to put his work in its proper place.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Liam Kofi Bright on Knowledge, Truth, and Science

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Everybody talks about the truth, but nobody does anything about it. And to be honest, how we talk about truth — what it is, and how to get there — can be a little sloppy at times. Philosophy to the rescue! I had a very ambitious conversation with Liam Kofi Bright, starting with what we mean by “truth” (correspondence, coherence, pragmatist, and deflationary approaches), and then getting into the nitty-gritty of how we actually discover it. There’s a lot to think about once we take a hard look at how science gets done, how discoveries are communicated, and what different kinds of participants can bring to the table.

Everybody talks about the truth, but nobody does anything about it. And to be honest, how we talk about truth — what it is, and how to get there — can be a little sloppy at times. Philosophy to the rescue! I had a very ambitious conversation with Liam Kofi Bright, starting with what we mean by “truth” (correspondence, coherence, pragmatist, and deflationary approaches), and then getting into the nitty-gritty of how we actually discover it. There’s a lot to think about once we take a hard look at how science gets done, how discoveries are communicated, and what different kinds of participants can bring to the table.

More here.

COVID-19 vaccine primer: 100-plus in the works, 8 in clinical trials

Beth Mole in Ars Technica:

The clearest way out of the COVID-19 crisis is to develop a safe, effective vaccine—and scientists have wasted no time in getting started.

They have at least 102 vaccine candidates in development worldwide. Eight of those have already entered early clinical trials in people. At least two have protected a small number of monkeys from infection with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, that causes COVID-19.

Some optimistic vaccine developers say that, if all goes perfectly, we could see large-scale production and limited deployment of vaccines as early as this fall. If true, it would be an extraordinary achievement. Less than four months ago, SARS-CoV-2 was an unnamed, never-before-seen virus that abruptly emerged in the central Chinese city of Wuhan. Researchers there quickly identified it and, by late January, had deciphered and shared its genetic code, allowing researchers around the world to get to work on defeating it. By late February, researchers on multiple continents were working up clinical trials for vaccine candidates. By mid-March, two of them began, and volunteers began receiving the first jabs of candidate vaccines against COVID-19.

It’s a record-setting feat. But, it’s unclear if researchers will be able to maintain this break-neck pace.

Generally, vaccines must go through three progressively more stringent human trial phases before they are considered safe and effective.

More here.

The World After Coronavirus: Adil Najam interviews Francis Fukuyama about the Future of Democracy

DNA Could Hold Clues to Varying Severity of COVID-19

Marla Broadfoot in The Scientist:

Among the many mysteries that remain about COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, is why it hits some people harder than others. Millions of people have been infected, but many never get sick. Those who do can experience an ever-expanding array of symptoms, including loss of smell or taste, pink eye, digestive issues, fever, cough, and difficulty breathing. Although the elderly, those with pre-existing conditions such as heart disease, and men are most likely to suffer severe complications, hundreds of young and previously healthy people have died from the disease in the US alone. In recent weeks, researchers have begun asking whether genetics could influence the severity of symptoms. So far, they know “basically nothing,” Wendy Chung, a clinical geneticist and physician at Columbia University, tells The Scientist. She is one of hundreds of scientists launching studies to interrogate the human genome for answers. Chung and her team are racing to “recycle” and bank nasal swabs and other clinical samples from COVID-19 patients across the New York-Presbyterian Hospital System, currently in the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic.

Among the many mysteries that remain about COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, is why it hits some people harder than others. Millions of people have been infected, but many never get sick. Those who do can experience an ever-expanding array of symptoms, including loss of smell or taste, pink eye, digestive issues, fever, cough, and difficulty breathing. Although the elderly, those with pre-existing conditions such as heart disease, and men are most likely to suffer severe complications, hundreds of young and previously healthy people have died from the disease in the US alone. In recent weeks, researchers have begun asking whether genetics could influence the severity of symptoms. So far, they know “basically nothing,” Wendy Chung, a clinical geneticist and physician at Columbia University, tells The Scientist. She is one of hundreds of scientists launching studies to interrogate the human genome for answers. Chung and her team are racing to “recycle” and bank nasal swabs and other clinical samples from COVID-19 patients across the New York-Presbyterian Hospital System, currently in the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic.

The researchers plan to extract the patients’ DNA and scan the genomes for tiny sequence variations associated with symptoms listed in their electronic health records. Prior research has uncovered gene variants that can alter a person’s chances of contracting an infectious disease. The most famous example is a mutation in the CCR5 gene, which offers protection against HIV. Other variants can affect what happens once the virus is inside the human body, leading to strikingly disparate outcomes from one person to the next, says Priya Duggal, a geneticist at Johns Hopkins University. Duggal has previously shown that variants in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes, which influence the body’s immune response, may explain why some people spontaneously clear hepatitis C infection whereas others are left with chronic disease.

More here.

Self-Isolated at the End of the World

Dennis Overbye in The New York Times:

More than once recently, I have lain awake counting the sirens going up the otherwise empty streets of Manhattan, wondering if their number might serve as a metric for how bad the coming day would be. But I know that none of my days could approach what Adm. Richard E. Byrd, the American arctic explorer, endured in 1934, when he spent five months alone in a one-room shack in Antarctica, wintering over the long night. January 2020 was the 200th anniversary of the first sighting of Antarctica, by Russian sailors. Byrd’s account of his 1934 ordeal, “Alone,” published in 1938, has been sitting by my bedside; call it the ultimate experiment in social distancing. At the time, Byrd was already famous for having been the first person to fly over the North Pole (although some researchers have disputed that claim) and, later, over the South Pole. He had received three ticker tape parades on Broadway. “My footless habits were practically ruinous to those who had to live with me,” he wrote. “Remembering the way it all was, I still wonder how my wife succeeded in bringing up four such splendid children as ours, wise each in his or her way.”

More than once recently, I have lain awake counting the sirens going up the otherwise empty streets of Manhattan, wondering if their number might serve as a metric for how bad the coming day would be. But I know that none of my days could approach what Adm. Richard E. Byrd, the American arctic explorer, endured in 1934, when he spent five months alone in a one-room shack in Antarctica, wintering over the long night. January 2020 was the 200th anniversary of the first sighting of Antarctica, by Russian sailors. Byrd’s account of his 1934 ordeal, “Alone,” published in 1938, has been sitting by my bedside; call it the ultimate experiment in social distancing. At the time, Byrd was already famous for having been the first person to fly over the North Pole (although some researchers have disputed that claim) and, later, over the South Pole. He had received three ticker tape parades on Broadway. “My footless habits were practically ruinous to those who had to live with me,” he wrote. “Remembering the way it all was, I still wonder how my wife succeeded in bringing up four such splendid children as ours, wise each in his or her way.”

He also drank a lot — perhaps, his companions later suggested, because he was quietly terrified of the flying that made him famous. Several of Byrd’s Arctic and Antarctic expeditions were sponsored by The New York Times. He was a personal friend of Arthur Hays Sulzberger, publisher of the newspaper from 1935 to 1961. On his first expedition to Antarctica, in 1929, Byrd mapped and named a number of mountains and other features on the continent, including several for the members of the Sulzberger family, which still runs The Times.

On his second expedition to Antarctica, from 1933 to 1935, Byrd, accompanied by a crew of more than four dozen men, sled dogs and a cow, hoped to increase the scope of his efforts from his established base on the coast, called Little America, into the interior of the continent, where the weather dynamics were unknown. He hit on the idea of wintering over through the entire dark Antarctic night, from April to October, to make meteorological and other scientific measurements. The Advance Base that Byrd and his crew eventually established was 178 miles away — a treacherous, crevasse-laden journey across the Ross Ice Shelf.

More here.

Living in bubbles

by Charlie Huenemann

“Every country is going through these decisions, none of us are through this pandemic yet, but some countries are starting to look at slightly expanding what people would define as their household — encouraging people who live alone to maybe match up with somebody else who is on their own or a couple of other people to have almost kind of bubbles of people,” she [Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon] told BBC Radio Scotland.

“Want to join my bubble? This is what your future social life could look like”, Angela Dewan, CNN, April 29th, 2020.

A crisis, by definition, has dramatic effects. It changes how we behave, where wealth goes, what policies we enact, and what we hope. But it also can bring into higher relief features of our lives that have not changed, but turn out to be more important than we realized.

Like the fact that human life takes place in bubbles. This just means that humans like to form groups: somewhat closed networks of interactive relationships among a small number of relatives or friends whose principal job it is to care for one another. “Semi-permeable palliative social matrices” one could call them, but “bubbles” will work just fine. A bubble is an enclosed space, protected from the outside by a fragile boundary; all its points are equidistant from a center; it is almost invisible, but offers a hopeful shine when the light hits it right. All the same can be said of a circle of good friends. And all of human history has been built upon such bubbles.

This crucial anthropological insight has been explored in nearly inexhaustible depth by the contemporary philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, particularly in his trilogy Spheres. Humans are born from round wombs into family circles, sometimes gathered in igloos and tipis, or around a hearth, following a circle of seasons under the orbs of moon and sun, growing into adulthood before they start the cycle again. Read more »

Monday Poem

I look at my grandchildren and know that, being so young, they have little

serious understaning of Covid and wonder what parts of it they’ll recall.

Or will it linger…? How vague a memory will it be. What sort of meaning

will it have, one like mine of world war?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Meaning of the Thing

—May 8, 1945

Suddenly Mom ran out the door,

she’d yanked it’s stubborn latch-side free

bolting into open air

thick with sirens, bells,

the horns of cars, ecstatic yells,

everything that blew that May day free,

crammed with audible relief,

cacophonous confetti,

in a joyous requiem for war:

the death of hell

Mom sobbed kneeling in the drive

and thanked the god who’d just undone

his bloody recklessness by fiat & surprise,

suddenly, in May— coincidental with

when life re-bounds

and I said, Mom, what’s wrong,

what are you crying for?

—and she: It’s done!

—and I: What’s done?

—and she: the War!

…… as if I’d known the meaning

of the thing at four

Jim Culleny

4/21/20

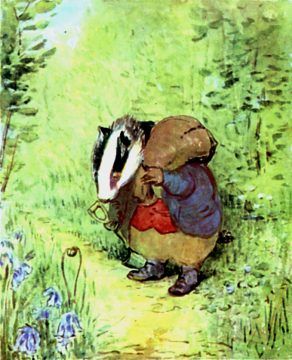

The Badgers of Montpelier Hill

by Liam Heneghan

When I was a child growing up in Dublin, a friend dropped her pet hamster on the kitchen floor. The animal survived but thereafter he could only walk in circles. As the hamster got older, the circles got wider but like a ship permanently anchored to shore it never got particularly far.

Like most children, I had taken a fall or two and because I was a worrier I felt concerned that like that hamster I would never travel very far. Though I did, indeed, travel and I am now thousands of miles from home, I still think of my life as occurring in a series of ever widening circles.

At first, I was confined to our back garden. We lived in the Templeogue Village an inglorious suburb on what at the time was a trailing edge of Dublin. Over the garden wall were farm fields and farther off were the Dublin Mountains.

Sure enough over the years, I explored the fields and when I got a little older, I would cycle into the foothills of those mountains.

Now there was one hill in particular that I was drawn to: officially called Montpelier Hill it is also called The Hell Fire Club. The story was that a structure built there in the early 1700s as a hunting lodge for delinquent aristocratic youth had also been used by them for somewhat darker practices. One night the devil himself showed up there at a card game. In the hubbub that followed, a candle was knocked over and the lodge burned to the ground. By the time I started to cycle there, The Hellfire Club was an innocuous forestry plantation. The burned lodge remains. Read more »

Let’s Not Allow Our Renewing Trust in Science to Become the Latest Victim of Covid-19

by Joseph Shieber

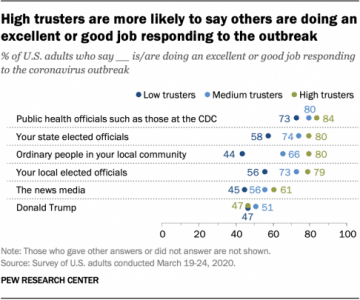

One of the heartening ramifications of the otherwise devastating Covid-19 pandemic has been the public’s high level of trust in science and expertise. As a March 19-24 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center indicates, over ⅔ even of low-trusting people surveyed trust public health officials to do an excellent or good job in dealing with the outbreak.

In fact, even corporate Twitter accounts for shaved meat products can boost their following by amplifying the experts:

This increased trust in scientific expertise is part of a growing trend. A Pew Research study in 2019 found that, since 2016, when less than ¼ of the public had “A great deal” of confidence that scientists act in the best interests of the public, by 2019 more than ⅓ of the public expressed “A great deal” of confidence in the actions of scientists.

The rising levels of trust in scientific expertise stand, however, in stark contrast to the current UIS Administration’s flagrant disregard of science. Indeed, the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School and the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund have tracked 417 “government attempts to restrict or prohibit scientific research, education or discussion, or the publication or use of scientific information” since the 2016 election. Read more »

Perceptions

A Letter to My Child in These Strange Times

by Samia Altaf

My son, it was reassuring to talk to you. We’re lucky that communication has become so easy, though I’d rather hold your dear face in my hands.

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

My mother, my “party,” was invariably in the kitchen when she was called to the phone. I could almost see her wiping her hands on the edge of her dupatta as she hurried over to scream How are you? into the phone. We’d talk about what she was cooking and other ordinary things. The world was safer then. No need to worry about face masks and sanitizers and such. The phone system that you laugh at did not seem too cumbersome then or too difficult—just normal for that time, even advanced. We thought we were lucky to be able to get to talk to folks back home, ten thousand miles away, on the other side of the world. Even grandma, Baiji, half deaf and half zonked on meds, was brought to the phone, and allowed to say Who? What? Read more »