Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

THE FIRST PERSON YOU MEET in New Yorker journalist Ben Taub’s Pulitzer-winning story “Guantánamo’s Darkest Secret” is the kindly guard. Steve Wood, a member of the Oregon National Guard, was deployed to the Guantánamo Bay detention facility. Despite being told to “never turn your back” on prisoners, Wood befriended one. Prisoner 760, as he was called, is Mohamedou Ould Salahi, a man kept in a trailer called “Echo Special” whose identity was so secret that his name did not even appear in the log of America’s cruelest prison.

THE FIRST PERSON YOU MEET in New Yorker journalist Ben Taub’s Pulitzer-winning story “Guantánamo’s Darkest Secret” is the kindly guard. Steve Wood, a member of the Oregon National Guard, was deployed to the Guantánamo Bay detention facility. Despite being told to “never turn your back” on prisoners, Wood befriended one. Prisoner 760, as he was called, is Mohamedou Ould Salahi, a man kept in a trailer called “Echo Special” whose identity was so secret that his name did not even appear in the log of America’s cruelest prison.

…If Wood is a kindly white guard who just wants to learn about Islam—he spends a lot of time at the base library reading up—then the new hero of the story is Taub himself. Great cruelties may have been inflicted at Guantánamo, New Yorker readers can tell themselves, but brave young journalists are out to expose them so that those educated well-off readers can sadly shake their heads. Except that those cruelties had already been exposed. Taub’s article was published in 2019, slightly more than four years after Salahi himself published his best-selling Guantánamo Diary, which notably did not win a Pulitzer Prize. Large parts of “Guantánamo’s Darkest Secret”—awarded a Pulitzer this week in the Feature Writing category—particularly those that deal with Salahi, rehash with the customary “he wrote” what had already been written. Yet while the content may be mostly the same, the purpose is different. Taub, unlike Salahi, is out to deliver absolution to his American reader: casting Steve Wood as an integral player is one part of this; leaving the still-constrained reality of Salahi’s present (he cannot leave tiny Mauritania) to the very end of the piece is another.

Indeed, while Salahi (whose name has also been styled as Slahi) may have told many truths in his own book, it is Taub who gets to tell them in the pages of The New Yorker. Credibility and journalistic heroism, as each year’s prizes show, reside in the pages of prestige publications; the New York Times and the Washington Post are mainstays, and since the prizes were first opened up to include magazines in 2015, The New Yorker is as well. No truth is really a truth, particularly a courageous truth, until it appears in their pages. The brown man, the accused terrorist, the actual torture survivor Mohamedou Ould Salahi may have written a great book. But the definitive story about “Guantánamo’s Darkest Secret” is the one penned by Taub.

More here.

What is it you see, asks Rachael Z. DeLue, in Romare Bearden’s artwork? Why is it you just can’t stop looking? How is it they remain, decades after his death, sources of what Wallace Stevens calls “imperishable bliss”?

What is it you see, asks Rachael Z. DeLue, in Romare Bearden’s artwork? Why is it you just can’t stop looking? How is it they remain, decades after his death, sources of what Wallace Stevens calls “imperishable bliss”?

When I was a kid, I adored going over to my grandmother’s house and exploring her art room. To reach it, I wound past my grandmother’s collections of things in the living room and hall, most in service of her

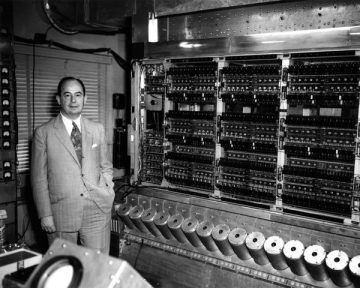

When I was a kid, I adored going over to my grandmother’s house and exploring her art room. To reach it, I wound past my grandmother’s collections of things in the living room and hall, most in service of her  That John von Neumann was one of the supreme intellects humanity has produced should be a statement beyond dispute. Both the lightning fast speed of his mind and the astonishing range of fields he made seminal contributions to made him a legend in his own lifetime. When he died in 1957 at the young age of 56 it was a huge loss; the loss of a great mathematician, a great polymath and to many, a great patriotic American who had done much to improve his country’s advantage in cutting-edge weaponry.

That John von Neumann was one of the supreme intellects humanity has produced should be a statement beyond dispute. Both the lightning fast speed of his mind and the astonishing range of fields he made seminal contributions to made him a legend in his own lifetime. When he died in 1957 at the young age of 56 it was a huge loss; the loss of a great mathematician, a great polymath and to many, a great patriotic American who had done much to improve his country’s advantage in cutting-edge weaponry. INDIAN CINEMA LOVES LOVE.

INDIAN CINEMA LOVES LOVE. If anybody profited from the war, it was us: its children. Apart from having survived it, we were richly provided with stuff to romanticize or to fantasize about. In addition to the usual childhood diet of Dumas and Jules Verne, we had military paraphernalia, which always goes well with boys. With us, it went exceptionally well, since it was our country that won the war.

If anybody profited from the war, it was us: its children. Apart from having survived it, we were richly provided with stuff to romanticize or to fantasize about. In addition to the usual childhood diet of Dumas and Jules Verne, we had military paraphernalia, which always goes well with boys. With us, it went exceptionally well, since it was our country that won the war.

As scientists work to create a vaccine against COVID-19, a small but fervent anti-vaccination movement is marshalling against it. Campaigners are seeding outlandish narratives: they falsely say that coronavirus vaccines will be used to implant microchips into people, for instance, and falsely claim that a woman who took part in a UK vaccine trial died. In April, some carried placards with anti-vaccine slogans at rallies in California to protest against the lockdown. Last week, a now-deleted YouTube video promoting wild conspiracy theories about the pandemic and asserting (without evidence) that vaccines would “kill millions” received more than 8 million views.

As scientists work to create a vaccine against COVID-19, a small but fervent anti-vaccination movement is marshalling against it. Campaigners are seeding outlandish narratives: they falsely say that coronavirus vaccines will be used to implant microchips into people, for instance, and falsely claim that a woman who took part in a UK vaccine trial died. In April, some carried placards with anti-vaccine slogans at rallies in California to protest against the lockdown. Last week, a now-deleted YouTube video promoting wild conspiracy theories about the pandemic and asserting (without evidence) that vaccines would “kill millions” received more than 8 million views. When Dwight D. Eisenhower was planning the invasion of Normandy, he made sure to check with Walter Munk and his colleagues first. Munk had come to the United States from Austria-Hungary to work as a banker before switching to oceanography, eventually making major advances in the science of tidal and wave forecasting. He was a defense researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1944 when his team calculated that the seas on June 5 of that year would be so rough that a delay was in order. The invasion would happen on the following day.

When Dwight D. Eisenhower was planning the invasion of Normandy, he made sure to check with Walter Munk and his colleagues first. Munk had come to the United States from Austria-Hungary to work as a banker before switching to oceanography, eventually making major advances in the science of tidal and wave forecasting. He was a defense researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1944 when his team calculated that the seas on June 5 of that year would be so rough that a delay was in order. The invasion would happen on the following day. Hutchins was coming off of an epic, exhausting week at Defcon, one of the world’s largest hacker conferences, where he had been celebrated as a hero. Less than three months earlier, Hutchins had saved the internet from what was, at the time, the worst cyberattack in history: a piece of

Hutchins was coming off of an epic, exhausting week at Defcon, one of the world’s largest hacker conferences, where he had been celebrated as a hero. Less than three months earlier, Hutchins had saved the internet from what was, at the time, the worst cyberattack in history: a piece of  If you go to Wendy’s this week, there’s a good chance you

If you go to Wendy’s this week, there’s a good chance you  It’s not often that a paper attempts to take down an entire field. Yet, this past January, that’s precisely what University of New Hampshire assistant philosophy professor Subrena Smith’s

It’s not often that a paper attempts to take down an entire field. Yet, this past January, that’s precisely what University of New Hampshire assistant philosophy professor Subrena Smith’s  In Southern California, early health seekers embraced the sunshine, fresh air, and opportunity to sleep outdoors. To reap the benefits of particular microclimates, they often lived somewhat nomadically, circulating between various hotels, boarding houses, or crudely erected tent cities. Some traveled by horse-drawn house wagon, wandering the desert to take air and sun baths. A family in Pasadena pitched a carpet over tree branches and lived beneath the peaked shelter for six weeks. An ill Massachusetts man roamed the bucolic Ojai Valley with a cow, subsisting only on its raw milk until he claimed a miraculous recovery.

In Southern California, early health seekers embraced the sunshine, fresh air, and opportunity to sleep outdoors. To reap the benefits of particular microclimates, they often lived somewhat nomadically, circulating between various hotels, boarding houses, or crudely erected tent cities. Some traveled by horse-drawn house wagon, wandering the desert to take air and sun baths. A family in Pasadena pitched a carpet over tree branches and lived beneath the peaked shelter for six weeks. An ill Massachusetts man roamed the bucolic Ojai Valley with a cow, subsisting only on its raw milk until he claimed a miraculous recovery. You will have seen art from the Edo Period—its most recognizable images are the ukiyo-e prints: mass-produced woodblock scenes of popular entertainment and Japanese landscapes, the most world-famous of which is Katushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa from 1829. These prints were ubiquitous, disseminated through the city’s pleasure quarters, and sold, it’s colloquially said, as cheaply as a second helping of noodles. And before Edo Japan opened up to the world and these inexpensive prints were splashed all over Europe, they were bought almost exclusively as souvenirs by a growing Japanese middle class, a pictorial keepsake of insular pride. The Great Wave is itself an amalgam of some of Japan’s most distinctive characteristics, illustrating its relationship with the spiritual anchor of Mount Fuji, and with the sea itself, which is embodied in both the quotidian economics of the fishing industry, and in the Buddhist philosophy of a wave’s impermanence.

You will have seen art from the Edo Period—its most recognizable images are the ukiyo-e prints: mass-produced woodblock scenes of popular entertainment and Japanese landscapes, the most world-famous of which is Katushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa from 1829. These prints were ubiquitous, disseminated through the city’s pleasure quarters, and sold, it’s colloquially said, as cheaply as a second helping of noodles. And before Edo Japan opened up to the world and these inexpensive prints were splashed all over Europe, they were bought almost exclusively as souvenirs by a growing Japanese middle class, a pictorial keepsake of insular pride. The Great Wave is itself an amalgam of some of Japan’s most distinctive characteristics, illustrating its relationship with the spiritual anchor of Mount Fuji, and with the sea itself, which is embodied in both the quotidian economics of the fishing industry, and in the Buddhist philosophy of a wave’s impermanence. THE FIRST PERSON YOU MEET

THE FIRST PERSON YOU MEET  Before

Before