Jack Zipes in Tribune:

Jack Zipes in Tribune:

Ernst Bloch was born in Ludwigshafen, Germany, in 1885. His parents were assimilated, well-to-do Jews, who had clear, but narrow expectations for Bloch and his future. At that time, however, during his youth he was more bothered by the void in his own life. His home was characterised by what he called “musty” — dreariness, lack of love, understanding, and stimulation. The Jewish religion played a minor role in his life and was meaningless in his family. He could only compensate for the gaps between him, his family, and their beliefs by filling the void with daydreams, voracious reading of fairy tales, popular literature, classics, philosophy, music and visits to the opera house and theater as well as letter-writing to eminent philosophers, rebellion against traditional schooling, and concern for social democratic politics.

To make up for the lack in his home and in Ludwigshafen, Bloch left in 1905 to study philosophy and German literature at the University of Munich and then at the University of Würzburg, where he focused on experimental psychology, physics, and music and took an interest in the Kabbala and Jewish mysticism. After receiving his doctorate in philosophy in 1908, he moved to Berlin to study under the renowned sociologist Georg Simmel, and it was in Simmel’s seminar that he made the acquaintance of Georg Lukács, the great Hungarian political theorist, who became one of his best friends and later one of his foremost philosophical antagonists.

More here.

Isabella Weber in Global Perspectives:

Isabella Weber in Global Perspectives: Kierkegaard commonly complained that he was misunderstood (he also complained that he was not misunderstood in the right ways). But few philosophers have wanted so keenly to be of use, according to a new biography, “Philosopher of the Heart,” by Clare Carlisle. Not for Kierkegaard the abstractions of philosophy — he saw the discipline as performing the painful, prosaic work of becoming human: “We must work out who we are, and how to live, right in the middle of life itself, with an open future ahead of us,” Carlisle summarizes his approach. “Just as we cannot step off the train while it is moving, so we cannot step away from life to reflect on its meaning.” There are famous challenges to telling the life of Kierkegaard. He died at 42, in Copenhagen, seemingly exhausted after an extraordinary burst of productivity that gave us a flotilla of philosophical texts masquerading as sermons, dialogues, found documents, book reviews.

Kierkegaard commonly complained that he was misunderstood (he also complained that he was not misunderstood in the right ways). But few philosophers have wanted so keenly to be of use, according to a new biography, “Philosopher of the Heart,” by Clare Carlisle. Not for Kierkegaard the abstractions of philosophy — he saw the discipline as performing the painful, prosaic work of becoming human: “We must work out who we are, and how to live, right in the middle of life itself, with an open future ahead of us,” Carlisle summarizes his approach. “Just as we cannot step off the train while it is moving, so we cannot step away from life to reflect on its meaning.” There are famous challenges to telling the life of Kierkegaard. He died at 42, in Copenhagen, seemingly exhausted after an extraordinary burst of productivity that gave us a flotilla of philosophical texts masquerading as sermons, dialogues, found documents, book reviews. The House of Habsburg has a plausible claim to having been the most successful ruling dynasty in world history. For a thousand years, from the dynasty’s emergence as feudal warlords in northern Switzerland in the 10th century to their ousting as emperors of Austria in the early 20th, they reigned at one time or another in most European countries (including, briefly, England and Ireland), and over colonial possessions that reached across the globe, from Peru to the Philippines (the one nation that still bears the name of a Habsburg king).

The House of Habsburg has a plausible claim to having been the most successful ruling dynasty in world history. For a thousand years, from the dynasty’s emergence as feudal warlords in northern Switzerland in the 10th century to their ousting as emperors of Austria in the early 20th, they reigned at one time or another in most European countries (including, briefly, England and Ireland), and over colonial possessions that reached across the globe, from Peru to the Philippines (the one nation that still bears the name of a Habsburg king). “IT’S LIKE WE’RE AT THE CENTER

“IT’S LIKE WE’RE AT THE CENTER  Of the films of the great Indian director Satyajit Ray, the Japanese master Akira Kurosawa once said that not having seen them “is like never having seen the sun or the moon.” I completely agree. For me, Ray is perhaps the finest of all film artists. The humanism of his vision, and the lyricism he brings to it, is overwhelming. No other director has so consistently expressed what it means to be alive. No other filmmaker, male or female, has explored with such profound grace and understanding the inner lives of women. I had the honor in the fall of 2008 to be invited to Kolkata, India, to lecture to local students and film societies about his work. As a white Westerner, I was wary of coming across like some sort of postcolonial know-it-all. I needn’t have worried. Our shared love for Ray dissolved any barriers. I was accompanied by a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences who was instrumental in the ongoing restoration of Ray’s films, many of which were in a state of disrepair. (Ray was awarded an honorary Oscar in 1992, shortly before his death.)

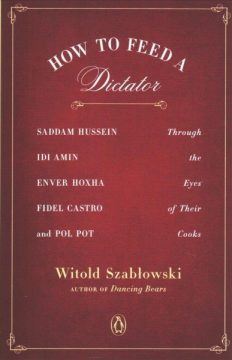

Of the films of the great Indian director Satyajit Ray, the Japanese master Akira Kurosawa once said that not having seen them “is like never having seen the sun or the moon.” I completely agree. For me, Ray is perhaps the finest of all film artists. The humanism of his vision, and the lyricism he brings to it, is overwhelming. No other director has so consistently expressed what it means to be alive. No other filmmaker, male or female, has explored with such profound grace and understanding the inner lives of women. I had the honor in the fall of 2008 to be invited to Kolkata, India, to lecture to local students and film societies about his work. As a white Westerner, I was wary of coming across like some sort of postcolonial know-it-all. I needn’t have worried. Our shared love for Ray dissolved any barriers. I was accompanied by a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences who was instrumental in the ongoing restoration of Ray’s films, many of which were in a state of disrepair. (Ray was awarded an honorary Oscar in 1992, shortly before his death.) In the new book How to Feed a Dictator, journalist Witold Szablowski tracks down the chefs who served these five men, to paint intimate portraits of how they were at home and at the table.

In the new book How to Feed a Dictator, journalist Witold Szablowski tracks down the chefs who served these five men, to paint intimate portraits of how they were at home and at the table.

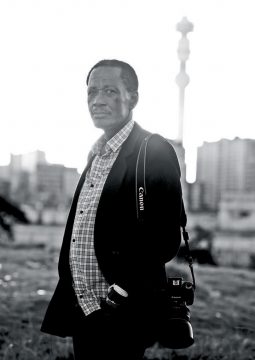

THERE IS A CERTAIN PROFUNDITY—a profundity that can only be qualified and quantified as tautology—a deep profundity in Santu Mofokeng’s work, which thrusts the viewers, if they are willing to listen to the images carefully, into a space of timelessness. A timelessness that speaks of the elasticity of time beyond time, beyond geography. A deep time. Not in the geological, Huttonian sense of deep time, but as in time’s transience and transcendentality. A time beyond the temporality of the lived imagination. I have found myself in this time-space often when looking at and listening to Santu’s photographic series, particularly “Landscapes,” 1988–2010; “Poisoned Landscapes,” 2008; “Townships,” 1985–87; “Child-Headed Households,” 2007; “Train Church,” 1986; “Landscapes of Trauma,” 1997–2004; “Chasing Shadows,” 1996–2006; and “Ishmael,” 1984–2005.

THERE IS A CERTAIN PROFUNDITY—a profundity that can only be qualified and quantified as tautology—a deep profundity in Santu Mofokeng’s work, which thrusts the viewers, if they are willing to listen to the images carefully, into a space of timelessness. A timelessness that speaks of the elasticity of time beyond time, beyond geography. A deep time. Not in the geological, Huttonian sense of deep time, but as in time’s transience and transcendentality. A time beyond the temporality of the lived imagination. I have found myself in this time-space often when looking at and listening to Santu’s photographic series, particularly “Landscapes,” 1988–2010; “Poisoned Landscapes,” 2008; “Townships,” 1985–87; “Child-Headed Households,” 2007; “Train Church,” 1986; “Landscapes of Trauma,” 1997–2004; “Chasing Shadows,” 1996–2006; and “Ishmael,” 1984–2005. In 1986, when the director Mira Nair was scouting for her film Salaam Bombay! at the National School of Drama in New Delhi, she fixed her gaze on a young man from Jaipur. “I noticed his focus, his intensity, his very remarkable look—his hooded eyes,” she

In 1986, when the director Mira Nair was scouting for her film Salaam Bombay! at the National School of Drama in New Delhi, she fixed her gaze on a young man from Jaipur. “I noticed his focus, his intensity, his very remarkable look—his hooded eyes,” she  Although the nineteenth-century philosopher G.W.F. Hegel is known as a defender of bourgeois society and so of what came to be known after him as capitalism, I think the evidence suggests that his answer to these questions is far more negative than is widely recognized, and this in a distinctive sense that remains relevant today. I want to try to explain this counterintuitive claim. Hegel, of course, writing in Germany in the early nineteenth century, had no idea of the full scope of the industrial capitalism to come, but he certainly saw that a largely agricultural and artisanal/craft/predominantly homebound economy was changing into a wage-labor economy, and his worries about that alone are apposite. What makes him especially worth returning to in our present circumstances, however, is that while material inequalities and the resulting systematic unfairness were important to him, Hegel’s principal focus was on the experiences of ourselves and others inherent in the ordinary life required by such a productive system. These issues are often misleadingly marginalized as “psychological,” but as recent events have shown, they are crucial to the possibility of the social bonds without which no society can survive.

Although the nineteenth-century philosopher G.W.F. Hegel is known as a defender of bourgeois society and so of what came to be known after him as capitalism, I think the evidence suggests that his answer to these questions is far more negative than is widely recognized, and this in a distinctive sense that remains relevant today. I want to try to explain this counterintuitive claim. Hegel, of course, writing in Germany in the early nineteenth century, had no idea of the full scope of the industrial capitalism to come, but he certainly saw that a largely agricultural and artisanal/craft/predominantly homebound economy was changing into a wage-labor economy, and his worries about that alone are apposite. What makes him especially worth returning to in our present circumstances, however, is that while material inequalities and the resulting systematic unfairness were important to him, Hegel’s principal focus was on the experiences of ourselves and others inherent in the ordinary life required by such a productive system. These issues are often misleadingly marginalized as “psychological,” but as recent events have shown, they are crucial to the possibility of the social bonds without which no society can survive. The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has renewed academic and clinical interest in an old vaccine,

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has renewed academic and clinical interest in an old vaccine,