Worthy of a Ghazal

…—for Tammara Claire

Had the heart been a bird it would have flown

to your courtyard carefully wrapping a ghazal

in a paper drenched in some Arabian aromas

landing on the bricked cope of a rural home

dropping words on your head making you

look for me but my absence is meager in this

world where love is not a panegyric rather

a dirge of nations, of mobs, of oligarchies

latching to thrones but you need not worry

feeding white ducks removing that curl from

your sweating forehead squeezing clothes on

a creaky bucket, let me give you a hand making

another ghazal on your hennaed feet, last night

you smiled through patterns embroiling your

wheatish skin on which I sit like a long memory

but earth-bound I review my majestic plans of

wooing you out of a structure surrounded by

marsh and yelping night-dogs but in my maqta

you appear free and shying, deserving conclusion.

by Rizwan Akhtar

from blognostics.net

*Maqta is the last couplet in ghazal in which the poet uses his name

“I spoke for you,” the qawwal said.

“I spoke for you,” the qawwal said. The skull in Vanitas Still Life, while undoubtedly grim, bears a wry, gapped grin—a grin missing four front teeth. Stripped of its flesh, our bone structure apparently discloses a faint, effortless smile. The skull’s stark, denuded presence signals gravity, but its blithe affect signals buoyancy. Perhaps this face of death reflects both the weeping Heraclitus and the laughing Democritus, pointing viewers back to Ecclesiastes: there is “a time to weep and a time to laugh.” Wisdom here comes lodged in apposition—pairs of apparent opposites, united by the word and: “a time to be born, and a time to die … a time to break down, and a time to build up … a time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together.” These lines in Ecclesiastes encourage readers to imagine a world in which the poles of existence create vibrant tension, in which life and death, gathering and releasing, embracing and refraining, weeping and laughing, do not negate each other but instead balance and enrich. There is aggregation and integration—even with loss, even in death.

The skull in Vanitas Still Life, while undoubtedly grim, bears a wry, gapped grin—a grin missing four front teeth. Stripped of its flesh, our bone structure apparently discloses a faint, effortless smile. The skull’s stark, denuded presence signals gravity, but its blithe affect signals buoyancy. Perhaps this face of death reflects both the weeping Heraclitus and the laughing Democritus, pointing viewers back to Ecclesiastes: there is “a time to weep and a time to laugh.” Wisdom here comes lodged in apposition—pairs of apparent opposites, united by the word and: “a time to be born, and a time to die … a time to break down, and a time to build up … a time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together.” These lines in Ecclesiastes encourage readers to imagine a world in which the poles of existence create vibrant tension, in which life and death, gathering and releasing, embracing and refraining, weeping and laughing, do not negate each other but instead balance and enrich. There is aggregation and integration—even with loss, even in death. More and more young Christians, disillusioned by the political binaries, economic uncertainties and spiritual emptiness that have come to define modern America, are finding solace in a decidedly anti-modern vision of faith. As the coronavirus and the subsequent lockdowns throw the failures of the current social order into stark relief, old forms of religiosity offer a glimpse of the transcendent beyond the present.

More and more young Christians, disillusioned by the political binaries, economic uncertainties and spiritual emptiness that have come to define modern America, are finding solace in a decidedly anti-modern vision of faith. As the coronavirus and the subsequent lockdowns throw the failures of the current social order into stark relief, old forms of religiosity offer a glimpse of the transcendent beyond the present. In the spring of 1822 an employee in one of the world’s first offices – that of the East India Company in London – sat down to write a letter to a friend. If the man was excited to be working in a building that was revolutionary, or thrilled to be part of a novel institution which would transform the world in the centuries that followed, he showed little sign of it. “You don’t know how wearisome it is”, wrote Charles Lamb, “to breathe the air of four pent walls, without relief, day after day, all the golden hours of the day between ten and four.” His letter grew ever-less enthusiastic, as he wished for “a few years between the grave and the desk”. No matter, he concluded, “they are the same.” The world that Lamb wrote from is now long gone. The infamous East India Company collapsed in ignominy in the 1850s. Its most famous legacy, British colonial rule in India, disintegrated a century later. But his letter resonates today, because, while other empires have fallen, the empire of the office has triumphed over modern professional life. The dimensions of this empire are awesome. Its population runs into hundreds of millions, drawn from every nation on Earth. It dominates the skylines of our cities – their tallest buildings are no longer cathedrals or temples but multi-storey vats filled with workers. It delineates much of our lives. If you are a hardworking citizen of this empire you will spend more waking hours with the irritating colleague to your left whose spare shoes invade your footwell than with your husband or wife, lover or children.

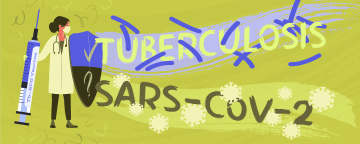

In the spring of 1822 an employee in one of the world’s first offices – that of the East India Company in London – sat down to write a letter to a friend. If the man was excited to be working in a building that was revolutionary, or thrilled to be part of a novel institution which would transform the world in the centuries that followed, he showed little sign of it. “You don’t know how wearisome it is”, wrote Charles Lamb, “to breathe the air of four pent walls, without relief, day after day, all the golden hours of the day between ten and four.” His letter grew ever-less enthusiastic, as he wished for “a few years between the grave and the desk”. No matter, he concluded, “they are the same.” The world that Lamb wrote from is now long gone. The infamous East India Company collapsed in ignominy in the 1850s. Its most famous legacy, British colonial rule in India, disintegrated a century later. But his letter resonates today, because, while other empires have fallen, the empire of the office has triumphed over modern professional life. The dimensions of this empire are awesome. Its population runs into hundreds of millions, drawn from every nation on Earth. It dominates the skylines of our cities – their tallest buildings are no longer cathedrals or temples but multi-storey vats filled with workers. It delineates much of our lives. If you are a hardworking citizen of this empire you will spend more waking hours with the irritating colleague to your left whose spare shoes invade your footwell than with your husband or wife, lover or children. One of the oldest vaccines could protect us against our newest infectious disease, COVID-19. The vaccine has been given to babies to protect them against tuberculosis for almost a century, but has been shown to shield them from other infections too, prompting scientists to investigate whether it can protect against the coronavirus. This Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, named after two French microbiologists, consists of a live weakened strain of Mycobacterium bovis, a cousin of M. tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. BCG has been given to more than 4 billion individuals, making it the most widely administered vaccine globally. Because BCG protects babies against some viral infections in addition to TB, researchers decided to compare data from countries with and without mandatory BCG vaccination to see if immunization policies are linked to the number or severity of COVID-19 infections. A handful of preprint publications in the last two months noted that countries with an ongoing BCG vaccination program are experiencing lower death rates from COVID-19 than those without.

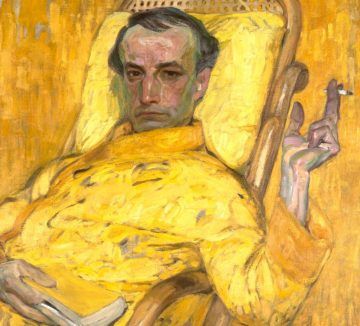

One of the oldest vaccines could protect us against our newest infectious disease, COVID-19. The vaccine has been given to babies to protect them against tuberculosis for almost a century, but has been shown to shield them from other infections too, prompting scientists to investigate whether it can protect against the coronavirus. This Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, named after two French microbiologists, consists of a live weakened strain of Mycobacterium bovis, a cousin of M. tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. BCG has been given to more than 4 billion individuals, making it the most widely administered vaccine globally. Because BCG protects babies against some viral infections in addition to TB, researchers decided to compare data from countries with and without mandatory BCG vaccination to see if immunization policies are linked to the number or severity of COVID-19 infections. A handful of preprint publications in the last two months noted that countries with an ongoing BCG vaccination program are experiencing lower death rates from COVID-19 than those without. I’m not ashamed to say that I bought Joris-Karl Huysmans’s Against Nature because of the cover: Frantisek Kupka’s The Yellow Scale (Self-Portrait) from 1907 is an exhilarating study of the color yellow. Its human subject, slouched in a wicker armchair, a cigarette dangling from one hand while a single, louche finger marks the page of a book, could be the perfect image of Des Esseintes, the dissolute antihero of Huysmans’s novel. Strictly speaking, the painting is a self-portrait of the habitually mustached Kupka, but it bears more than a passing resemblance to Charles Baudelaire, who haunts almost every page of Against Nature. This novel, about a dyspeptic aesthete who “took pleasure in a life of studious decrepitude,” spends some two hundred pages luxuriating in excess and opulence while the hero cuts himself off from the rest of society.

I’m not ashamed to say that I bought Joris-Karl Huysmans’s Against Nature because of the cover: Frantisek Kupka’s The Yellow Scale (Self-Portrait) from 1907 is an exhilarating study of the color yellow. Its human subject, slouched in a wicker armchair, a cigarette dangling from one hand while a single, louche finger marks the page of a book, could be the perfect image of Des Esseintes, the dissolute antihero of Huysmans’s novel. Strictly speaking, the painting is a self-portrait of the habitually mustached Kupka, but it bears more than a passing resemblance to Charles Baudelaire, who haunts almost every page of Against Nature. This novel, about a dyspeptic aesthete who “took pleasure in a life of studious decrepitude,” spends some two hundred pages luxuriating in excess and opulence while the hero cuts himself off from the rest of society. Stephen Wolfram blames himself for not changing the face of physics sooner.

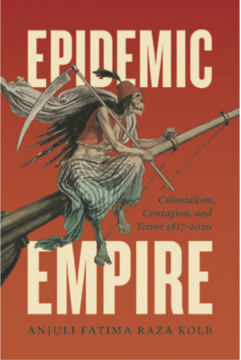

Stephen Wolfram blames himself for not changing the face of physics sooner. As the coronavirus began to take hold of our lives, our news, and became our undeniable, global, shared reality, I kept thinking about Anjuli Raza Kolb’s upcoming book,

As the coronavirus began to take hold of our lives, our news, and became our undeniable, global, shared reality, I kept thinking about Anjuli Raza Kolb’s upcoming book,  The book is Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day. Mayer wrote it, the whole thing, every word, on December 22, 1978. Before today, I’d read only parts, but this is a book to be swallowed whole, hour by hour, the way Mayer wrote it. Therefore, I’m currently parked in a chair in the Lebanon, New Hampshire, public library, attempting a small degree of penance through reading.

The book is Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day. Mayer wrote it, the whole thing, every word, on December 22, 1978. Before today, I’d read only parts, but this is a book to be swallowed whole, hour by hour, the way Mayer wrote it. Therefore, I’m currently parked in a chair in the Lebanon, New Hampshire, public library, attempting a small degree of penance through reading. I can’t think of another song that better approximates the soft, giddy feeling of something new suddenly opening up. The song’s first few movements—the album version is almost twenty-three minutes, in total—make me feel as if I have just crested a long hill. Kraftwerk wrote often about motion—the band was interested in ideas of repetition, inertia, speed—which might be part of why its records feel so transporting. To anyone who feels a desire to briefly depart Earth, I say cue up “

I can’t think of another song that better approximates the soft, giddy feeling of something new suddenly opening up. The song’s first few movements—the album version is almost twenty-three minutes, in total—make me feel as if I have just crested a long hill. Kraftwerk wrote often about motion—the band was interested in ideas of repetition, inertia, speed—which might be part of why its records feel so transporting. To anyone who feels a desire to briefly depart Earth, I say cue up “ Rashid Khalidi’s account of Jewish settlers’ conquest of Palestine is informed and passionate. It pulls no punches in its critique of Jewish-Israeli policies (policies that have had wholehearted US support after 1967), but it also lays out the failings of the Palestinian leadership. Khalidi participated in this history as an activist scion of a leading Palestinian family: in Beirut during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and as part of the Palestinian negotiating team prior to the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian peace accords. He slams Israel but his is also an elegy for the Palestinians, for their dispossession, for their failure to resist conquest. It is a relentless story of Jewish-Israeli bad faith, alongside one of Palestinian corruption and political short-sightedness.

Rashid Khalidi’s account of Jewish settlers’ conquest of Palestine is informed and passionate. It pulls no punches in its critique of Jewish-Israeli policies (policies that have had wholehearted US support after 1967), but it also lays out the failings of the Palestinian leadership. Khalidi participated in this history as an activist scion of a leading Palestinian family: in Beirut during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and as part of the Palestinian negotiating team prior to the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian peace accords. He slams Israel but his is also an elegy for the Palestinians, for their dispossession, for their failure to resist conquest. It is a relentless story of Jewish-Israeli bad faith, alongside one of Palestinian corruption and political short-sightedness. There’s an old belief that truth will always overcome error. Alas, history tells us something different. Without someone to fight for it, to put error on the defensive, truth may languish. It may even be lost, at least for some time. No one understood this better than the renowned Italian scientist Galileo Galilei. It is easy to imagine the man who for a while almost single-handedly founded the methods and practices of modern science as some sort of Renaissance ivory-tower intellectual, uninterested and unwilling to sully himself by getting down into the trenches in defense of science. But Galileo was not only a relentless advocate for what science could teach the rest of us. He was a master in outreach and a brilliant pioneer in the art of getting his message across. Today it may be hard to believe that science needs to be defended. But a political storm that denies the facts of science has swept across the land. This denialism ranges from the initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic to the reality of climate change. It’s heard in the preposterous arguments against vaccinating children and Darwin’s theory of evolution by means of natural selection. The scientists putting their careers, reputations, and even their health on the line to educate the public can take heart from Galileo, whose courageous resistance led the way.

There’s an old belief that truth will always overcome error. Alas, history tells us something different. Without someone to fight for it, to put error on the defensive, truth may languish. It may even be lost, at least for some time. No one understood this better than the renowned Italian scientist Galileo Galilei. It is easy to imagine the man who for a while almost single-handedly founded the methods and practices of modern science as some sort of Renaissance ivory-tower intellectual, uninterested and unwilling to sully himself by getting down into the trenches in defense of science. But Galileo was not only a relentless advocate for what science could teach the rest of us. He was a master in outreach and a brilliant pioneer in the art of getting his message across. Today it may be hard to believe that science needs to be defended. But a political storm that denies the facts of science has swept across the land. This denialism ranges from the initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic to the reality of climate change. It’s heard in the preposterous arguments against vaccinating children and Darwin’s theory of evolution by means of natural selection. The scientists putting their careers, reputations, and even their health on the line to educate the public can take heart from Galileo, whose courageous resistance led the way. Seventeen years after his death, Edward Said remains a powerful intellectual presence in academic and public discourse, a fact attested to by the appearance of two important new books. After Said, edited by Bashir Abu-Manneh, offers assessments of Said’s vast body of scholarship by a dozen noted writers and academics. The Selected Works of Edward Said, 1966–2006, edited by Moustafa Bayoumi and Andrew Rubin, two former students, is an expanded version of The Edward Said Reader, which was published a few years before his death in 2003. The Reader offered us a full picture of Said’s breadth and influence as a public intellectual; the new collection is more than 150 pages longer and includes eight essays that didn’t appear in the earlier volume, plus a new preface and an expanded introduction. The newly included essays range from overtly political sallies to reflective meditations on the “late style” in music and literature that were published posthumously. Some of them, like “Freud and the Non-European,” reflect concerns that preoccupied him toward the end of his life and are among the most complex and subtle of his writings. Others remind us how widely read he was, how broad his interests were, and how penetrating his insights could be. Coupled with the reflections on his major works in After Said, they also give the reader a sense of the consistency of his politics, imbued with a universalist and cosmopolitan humanism that sat at the center of his literary and political writings.

Seventeen years after his death, Edward Said remains a powerful intellectual presence in academic and public discourse, a fact attested to by the appearance of two important new books. After Said, edited by Bashir Abu-Manneh, offers assessments of Said’s vast body of scholarship by a dozen noted writers and academics. The Selected Works of Edward Said, 1966–2006, edited by Moustafa Bayoumi and Andrew Rubin, two former students, is an expanded version of The Edward Said Reader, which was published a few years before his death in 2003. The Reader offered us a full picture of Said’s breadth and influence as a public intellectual; the new collection is more than 150 pages longer and includes eight essays that didn’t appear in the earlier volume, plus a new preface and an expanded introduction. The newly included essays range from overtly political sallies to reflective meditations on the “late style” in music and literature that were published posthumously. Some of them, like “Freud and the Non-European,” reflect concerns that preoccupied him toward the end of his life and are among the most complex and subtle of his writings. Others remind us how widely read he was, how broad his interests were, and how penetrating his insights could be. Coupled with the reflections on his major works in After Said, they also give the reader a sense of the consistency of his politics, imbued with a universalist and cosmopolitan humanism that sat at the center of his literary and political writings. Upton Sinclair published

Upton Sinclair published