by Rafiq Kathwari

Mother passed away in her sleep at Hebrew Home, The Bronx. The last time I visited her was on 7th March. Hebrew Home locked down on the 10th. Mother died alone on 31 March. She was 96.

Mother’s caregiver, Sabila from Nepal, who over the last 10 years created an extraordinary bond with mother, called her Ami Jan, an endearment, and who follows the Hindu faith, once gave Mother a framed picture of Mother India or Bharat Mata, which Sabila thought symbolized her relationship with Mother who, in turn, taught Sabila to recite the first surah of the Koran which, consequently, Sabila did most beautifully and by heart.

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story.

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story.

One day, God Rama saw Sita bathing nude in Sitaharan a spring near the Line of Control in Kashmir: It was lust at first sight. Enter Ravana, demon king who abducted Sita to Sri Lanka to avenge a previous wrong, angering Rama who flew south to Lanka in his glitzy winged chariot Made in Prehistoric India using indigenous materials, piloted by a crew of monkeys.Rama, who shot a divine arrow which pierced Ravana in the heart and killed him, flew Sita back to Kashmir where legend has it they lived happily until India divided herself 73 years ago.

Mother said, broods of the Dogras want their land back, flora, fauna, valleys, peaks, pashmina goats, Mother said after I told her that Hindutva goons are calling it Zameen jihad. Of course, they will, she said. It’s the nature of fascists to clasp opposite concepts to serve their own propaganda. Read more »

For centuries western culture has been permeated by the idea that humans are selfish creatures. That cynical image of humanity has been proclaimed in films and novels, history books and scientific research. But in the last 20 years, something extraordinary has happened. Scientists from all over the world have switched to a more hopeful view of mankind. This development is still so young that researchers in different fields often don’t even know about each other.

For centuries western culture has been permeated by the idea that humans are selfish creatures. That cynical image of humanity has been proclaimed in films and novels, history books and scientific research. But in the last 20 years, something extraordinary has happened. Scientists from all over the world have switched to a more hopeful view of mankind. This development is still so young that researchers in different fields often don’t even know about each other. On a crisp afternoon, four cyclists pedaled mountain bikes along the serpentine two-lane byway on the southern shores of

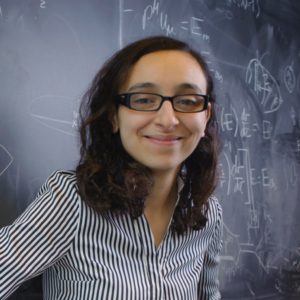

On a crisp afternoon, four cyclists pedaled mountain bikes along the serpentine two-lane byway on the southern shores of  The past few centuries of scientific progress have displaced humanity from the center of it all: the Earth is not at the middle of the Solar System, the Sun is but one star in a large galaxy, there are trillions of galaxies, and so on. Now we know that we’re not even made of the same stuff as most of the universe; for every amount of ordinary atoms and other known particles, there is five times as much dark matter, some kind of stuff we haven’t identified in laboratory experiments. But we do know a great deal about the behavior of dark matter. I talk with Lina Necib about why we think there’s dark matter, what it might be, and how it’s distributed in the galaxy. The latter question has seen enormous recent progress, especially from high-precision measurements of the distribution of stars in the Milky Way.

The past few centuries of scientific progress have displaced humanity from the center of it all: the Earth is not at the middle of the Solar System, the Sun is but one star in a large galaxy, there are trillions of galaxies, and so on. Now we know that we’re not even made of the same stuff as most of the universe; for every amount of ordinary atoms and other known particles, there is five times as much dark matter, some kind of stuff we haven’t identified in laboratory experiments. But we do know a great deal about the behavior of dark matter. I talk with Lina Necib about why we think there’s dark matter, what it might be, and how it’s distributed in the galaxy. The latter question has seen enormous recent progress, especially from high-precision measurements of the distribution of stars in the Milky Way. This is a good moment, then, for the Belgian architect Jean Dethier to release a 512-page survey chronicling earth construction from prehistory onwards across five continents. Proportioned and priced as a coffee table filler, the book is in fact ferociously polemical. Within pages, Dethier is raging against the climate-wrecking paradigm of contemporary construction: ‘The excessive use of industrialized building materials, often under the pretext of rationality, is one of the main causes of climate change.’ He argues that ‘prevailing building practices of today are often exploitative and dangerous, forced upon us by a lobby of multinational manufacturers of industrialized materials that have come to dominate our lives’.

This is a good moment, then, for the Belgian architect Jean Dethier to release a 512-page survey chronicling earth construction from prehistory onwards across five continents. Proportioned and priced as a coffee table filler, the book is in fact ferociously polemical. Within pages, Dethier is raging against the climate-wrecking paradigm of contemporary construction: ‘The excessive use of industrialized building materials, often under the pretext of rationality, is one of the main causes of climate change.’ He argues that ‘prevailing building practices of today are often exploitative and dangerous, forced upon us by a lobby of multinational manufacturers of industrialized materials that have come to dominate our lives’. “I hope you are able to work hard on science & thus banish, as far as may be possible, painful remembrances,” Charles Darwin wrote in the spring of 1864 to a young and obscure German correspondent who had just sent him two folios of his

“I hope you are able to work hard on science & thus banish, as far as may be possible, painful remembrances,” Charles Darwin wrote in the spring of 1864 to a young and obscure German correspondent who had just sent him two folios of his  A few years ago, one of my students came to me and spoke about her mother who was undergoing treatment for breast cancer. She said her mother was losing her memory and her bearings, and was very worried because nobody knew what to do about her symptoms. The oncologist sent her to the psychiatrist. The psychiatrist sent her back, saying that her symptoms were a result of the cancer treatment. This experience prompted my student and me to begin studying the problem of ‘chemobrain’ or ‘chemofog’ – the

A few years ago, one of my students came to me and spoke about her mother who was undergoing treatment for breast cancer. She said her mother was losing her memory and her bearings, and was very worried because nobody knew what to do about her symptoms. The oncologist sent her to the psychiatrist. The psychiatrist sent her back, saying that her symptoms were a result of the cancer treatment. This experience prompted my student and me to begin studying the problem of ‘chemobrain’ or ‘chemofog’ – the

The story of Trump’s rise is often told as a hostile takeover. In truth, it is something closer to a joint venture, in which members of America’s élite accepted the terms of Trumpism as the price of power. Long before anyone imagined that Trump might become President, a generation of unwitting patrons paved the way for him. From Greenwich and places like it, they launched a set of financial, philanthropic, and political projects that have changed American ideas about government, taxes, and the legitimacy of the liberal state.

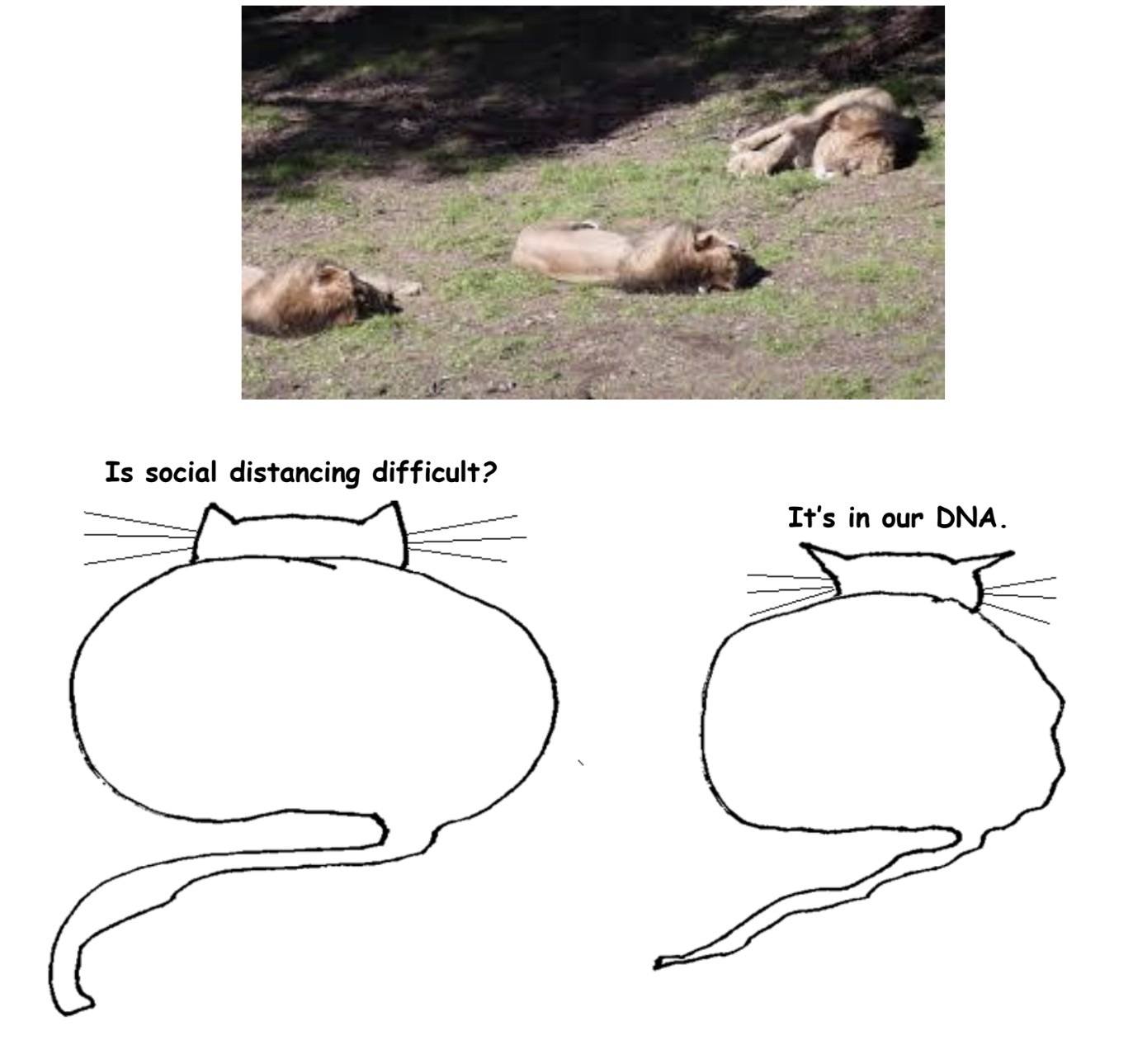

The story of Trump’s rise is often told as a hostile takeover. In truth, it is something closer to a joint venture, in which members of America’s élite accepted the terms of Trumpism as the price of power. Long before anyone imagined that Trump might become President, a generation of unwitting patrons paved the way for him. From Greenwich and places like it, they launched a set of financial, philanthropic, and political projects that have changed American ideas about government, taxes, and the legitimacy of the liberal state. Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague.

Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague. What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.

What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story.

So, here she is Bharat Mata, or as Sabila saw my mother, wrapped in a bright sari, superimposed on a map of India painted on a box of safety matches. It’s incendiary. Kashmir crowns the Mata who wields a trident in her right hand. A multi-color flag erases Afghanistan and Pakistan. Left-hand shadows Bangla Desh gesturing towards Myanmar. Her foot seems bigger than pearl-shaped Sri Lanka which forms the central story of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Here’s how Sabila told Mother the story. One of the things that fascinates me about history is the different ways we know historical periods. We know the times we live through in a very deep way, not just the events and how they affect us, but the details of daily life. We know the slang, the jokes, the mid-list books; the forgettable songs and the ephemeral news; what the world smells like and how it tastes and sounds. It’s very hard to know another time period in anything like the detail we know our own: what people wore to work, what they did on Saturday afternoons, what all the machines did and why they were made.

One of the things that fascinates me about history is the different ways we know historical periods. We know the times we live through in a very deep way, not just the events and how they affect us, but the details of daily life. We know the slang, the jokes, the mid-list books; the forgettable songs and the ephemeral news; what the world smells like and how it tastes and sounds. It’s very hard to know another time period in anything like the detail we know our own: what people wore to work, what they did on Saturday afternoons, what all the machines did and why they were made.