From Phys.Org:

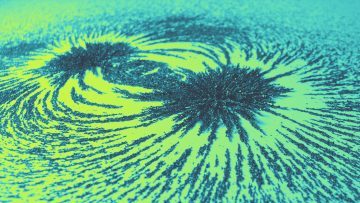

Scientists at the University of South Carolina and Columbia University have developed a faster way to design and make gas-filtering membranes that could cut greenhouse gas emissions and reduce pollution. Their new method, published today in Science Advances, mixes machine learning with synthetic chemistry to design and develop new gas-separation membranes more quickly. Recent experiments applying this approach resulted in new materials that separate gases better than any other known filtering membranes. The discovery could revolutionize the way new materials are designed and created, Brian Benicewicz, the University of South Carolina SmartState chemistry professor, said. “It removes the guesswork and the old trial-and-error work, which is very ineffective,” Benicewicz said. “You don’t have to make hundreds of different materials and test them. Now you’re letting the machine learn. It can narrow your search.”

Scientists at the University of South Carolina and Columbia University have developed a faster way to design and make gas-filtering membranes that could cut greenhouse gas emissions and reduce pollution. Their new method, published today in Science Advances, mixes machine learning with synthetic chemistry to design and develop new gas-separation membranes more quickly. Recent experiments applying this approach resulted in new materials that separate gases better than any other known filtering membranes. The discovery could revolutionize the way new materials are designed and created, Brian Benicewicz, the University of South Carolina SmartState chemistry professor, said. “It removes the guesswork and the old trial-and-error work, which is very ineffective,” Benicewicz said. “You don’t have to make hundreds of different materials and test them. Now you’re letting the machine learn. It can narrow your search.”

Plastic films or membranes are often used to filter gases. Benicewicz explained that these membranes suffer from a tradeoff between selectivity and permeability—a material that lets one gas through is unlikely to stop a molecule of another gas. “We’re talking about some really small molecules,” Benicewicz said. “The size difference is almost imperceptible. If you want a lot of permeability, you’re not going to get a lot of selectivity.” Benicewicz and his collaborators at Columbia University wanted to see if big data could design a more effective membrane. The team at Columbia University created a machine learning algorithm that analyzed the chemical structure and effectiveness of existing membranes used for separating carbon dioxide from methane. Once the algorithm could accurately predict the effectiveness of a given membrane, they turned the question around: What chemical structure would make the ideal gas separation membrane?

Sanat K. Kumar, the Bykhovsky Professor of Chemical Engineering at Columbia, compared it to Netflix’s method for recommending movies. By examining what a viewer has watched and liked before, Netflix determines features that the viewer enjoys and then finds videos to recommend. His algorithm analyzed the chemical structures of existing membranes and determined which structures would be more effective. The computer produced a list of 100 hypothetical materials that might surpass current limits.

More here.

According to the government, we are now supposed to be getting back to work. But what does “work” mean in the time of Covid-19? Amid the debates about how we might return to work, what is being forgotten is that work is a crucial part of what the 20th-century political philosopher Hannah Arendt called the human condition. The government’s Covid-19 recovery strategy, published on 11 May, states that people will be “eased back into work” as into a dentist chair: carefully, and with face masks.

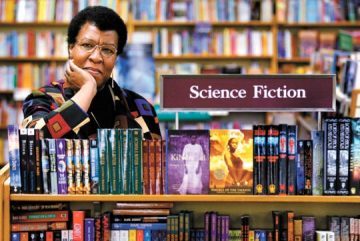

According to the government, we are now supposed to be getting back to work. But what does “work” mean in the time of Covid-19? Amid the debates about how we might return to work, what is being forgotten is that work is a crucial part of what the 20th-century political philosopher Hannah Arendt called the human condition. The government’s Covid-19 recovery strategy, published on 11 May, states that people will be “eased back into work” as into a dentist chair: carefully, and with face masks. A revolutionary voice in her lifetime, Butler has only become more popular and influential since her death 14 years ago, at age 58. Her novels, including “Dawn,” “Kindred” and “Parable of the Sower,” sell more than 100,000 copies each year, according to her former literary and the manager of her estate, Merrillee Heifetz. Toshi Reagon has adapted “Parable of the Sower” into an opera, and Viola Davis and Ava DuVernay are among those working on streaming series based on her work. Grand Central Publishing is reissuing many of her novels this year and the Library of America welcomes her to the canon in 2021 with a volume of her fiction.

A revolutionary voice in her lifetime, Butler has only become more popular and influential since her death 14 years ago, at age 58. Her novels, including “Dawn,” “Kindred” and “Parable of the Sower,” sell more than 100,000 copies each year, according to her former literary and the manager of her estate, Merrillee Heifetz. Toshi Reagon has adapted “Parable of the Sower” into an opera, and Viola Davis and Ava DuVernay are among those working on streaming series based on her work. Grand Central Publishing is reissuing many of her novels this year and the Library of America welcomes her to the canon in 2021 with a volume of her fiction. Edward Luce in the FT:

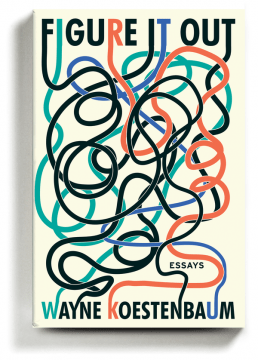

Edward Luce in the FT: Our most ecstatic modern practitioner might be Wayne Koestenbaum, the polymathic poet and essayist. (He’s also a painter and pianist.) His work — rueful, cerebral, gloriously smutty — includes trance poetry and automatic writing. He has published sections of his notebooks, trippy discursions into his obsessions with opera (“The Queen’s Throat”) and Jacqueline Onassis (“Jackie Under My Skin”), a novel about a hotel where the guest services include having your certainties shredded (“Hotel Theory”). Whatever his subject — favorites include porn, punctuation and the poetry of Frank O’Hara — the goal is always to jigger logic and language free of its moorings. “The writer’s obligation,” he states in his new essay collection, “Figure It Out,” “is to play with words and to keep playing with them, not to deracinate or deplete them, but to use them as vehicles for discovering history, recovering wounds, reciting damage and awakening conscience.”

Our most ecstatic modern practitioner might be Wayne Koestenbaum, the polymathic poet and essayist. (He’s also a painter and pianist.) His work — rueful, cerebral, gloriously smutty — includes trance poetry and automatic writing. He has published sections of his notebooks, trippy discursions into his obsessions with opera (“The Queen’s Throat”) and Jacqueline Onassis (“Jackie Under My Skin”), a novel about a hotel where the guest services include having your certainties shredded (“Hotel Theory”). Whatever his subject — favorites include porn, punctuation and the poetry of Frank O’Hara — the goal is always to jigger logic and language free of its moorings. “The writer’s obligation,” he states in his new essay collection, “Figure It Out,” “is to play with words and to keep playing with them, not to deracinate or deplete them, but to use them as vehicles for discovering history, recovering wounds, reciting damage and awakening conscience.” Kevin Hartnett in Quanta Magazine:

Kevin Hartnett in Quanta Magazine: Thomas Meaney in The New Yorker:

Thomas Meaney in The New Yorker: Rudrangshu Mukherjee reviews Partha K. Chatterjee’s I Am The People, in The India Forum:

Rudrangshu Mukherjee reviews Partha K. Chatterjee’s I Am The People, in The India Forum: Alex Gourevitch and Corey Robin in Polity:

Alex Gourevitch and Corey Robin in Polity: Inequality is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political.” Thomas Piketty’s latest book,

Inequality is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political.” Thomas Piketty’s latest book,  How will we live, or be forced to live, after the pandemic? “I don’t know” is—

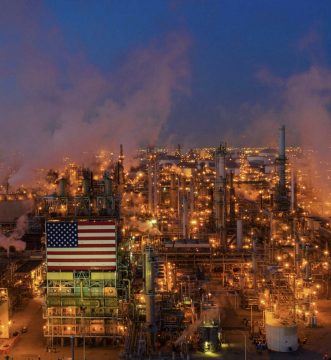

How will we live, or be forced to live, after the pandemic? “I don’t know” is— Recently, the Federal Reserve announced that it would be loosening its lending guidelines so that more corporations, even those with massive pre-existing debts, could take part in the bailout feeding frenzy.

Recently, the Federal Reserve announced that it would be loosening its lending guidelines so that more corporations, even those with massive pre-existing debts, could take part in the bailout feeding frenzy.  On a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility.

On a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility. Catherine the Great is a monarch mired in misconception. Derided both in her day and in modern times as a hypocritical warmonger with an unnatural sexual appetite, Catherine was a woman of contradictions whose brazen exploits have long overshadowed the accomplishments that won her “the Great” moniker in the first place.

Catherine the Great is a monarch mired in misconception. Derided both in her day and in modern times as a hypocritical warmonger with an unnatural sexual appetite, Catherine was a woman of contradictions whose brazen exploits have long overshadowed the accomplishments that won her “the Great” moniker in the first place. Beginning thousands of years before the first dairy restaurant appeared, Katchor’s book attempts to explicate the laws of kashruth—the separation of milk and meat—and other dietary notions and origin myths. (The mixture of causal logic and total irrationality recalls Katchor’s musical-theater piece The Slug Bearers of Kayrol Island, in which exploited workers transport tiny lead weights to place inside and give heft to small appliances.) Coffeehouse culture stimulates the Enlightenment. Radical puritans imagine a prelapsarian Hebrew vegetarian diet while, having internalized certain liberal values advanced by the French Revolution, eighteenth-century Parisians invent the “restaurant” and the “menu,” consecrated to individual rights and freedom of choice.

Beginning thousands of years before the first dairy restaurant appeared, Katchor’s book attempts to explicate the laws of kashruth—the separation of milk and meat—and other dietary notions and origin myths. (The mixture of causal logic and total irrationality recalls Katchor’s musical-theater piece The Slug Bearers of Kayrol Island, in which exploited workers transport tiny lead weights to place inside and give heft to small appliances.) Coffeehouse culture stimulates the Enlightenment. Radical puritans imagine a prelapsarian Hebrew vegetarian diet while, having internalized certain liberal values advanced by the French Revolution, eighteenth-century Parisians invent the “restaurant” and the “menu,” consecrated to individual rights and freedom of choice.