by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

Editor’s Note: Dear Reader, if you could share this interview on social media, by email, etc., it might be helpful in securing Ding Jiaxi’s release.

by Emrys Westacott

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.

One such person is Ding Jiaxi.

By any standards, Ding is a remarkable individual. Born in 1967 in a remote village in the mountains of Hubei province in central China, he won admission to Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, one of the top institutions for engineering research in the country. After graduation he conducted research in aircraft engineering, and while doing this simultaneously studied law and passed the bar exam. In 1997 he decided to switch careers and began working as a lawyer. In 2003, with a few partners he started a law firm that under his direction became highly successful over the next ten years, eventually bringing in an annual income of 25 million RMB. Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

As many of us head into our second month of shelter in place orders (or not in some cases), we are looking to the past for guidance on what comes next. Unsurprisingly, many wonder when does “normal” return. It’s a hopeful question, as after all, this is hardly the first devastating disease that humanity has wrestled with historically. Those previous pandemics brought out massive disruptions, sometimes for centuries after. Events like the Black Death in the 14th century, the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918, the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, and more recent scares such as swine flu, ebola, and zika, all had (or are still having) long lasting impacts—the aftermath was not back to normal, but a world transformed. But even the more recent public health emergencies seem distant problems to some.

AIDS for many still remains a “gay problem” rather than an actual, ongoing public health problem that needs a systemic response. For many white, straight people it was a “non-event” in their communities, something they experienced via the news rather than in their daily lives. The ones further in the past seem even less impactful, with the Spanish Flu as a prime example. Most narratives of the Great War told to the public ignore or downplay the role of the 1918 flu in reshaping the world. Part of that is a failure to understand how complexity of historical cause and effect. We don’t think of the Spanish Flu as disruptive, as it came at the end of the War, which gets all the public attention. But the world was pretty radically altered by the events of both the War and the pandemic: “normal” never fully returned. People lived transformed lives in the wake of both events. Here I want to argue that “normal” as we’ve come to experience it will most likely not return. Whatever changes come out of this pandemic need not be a negative if we proactively address the real cracks being revealed in our system. To quote the great Leonard Cohen, “there is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.” I argue we need to use that illumination to create a system of sustainability rather than one based on endless growth to nowhere. Read more »

by Katie Poore

A few months ago, before the news had spiraled into an endless spiral of public health precautions and death tolls, I was scrolling through Instagram, thinking, as one does while scrolling through Instagram, of nothing in particular. It had been a long day, and I was eager for those ten minutes of blank-mindedness, a strange and temporary forgetting as one melts into a digital universe. News of COVID-19 had just begun to spike where I had been living in Chambéry, France, close to the northern Italian border, and although it didn’t feel particularly urgent, I felt, as I almost always do, unsettled by the endless news cycle and the catastrophic events that have become so commonplace that the word catastrophic has begun to feel itself quotidian.

The news was bad, but Instagram was mostly anesthetizing, and anesthesia is what I sought. Thoughtlessness.

But it didn’t last long. Rather quickly I stumbled across a few snippets of a poem:

Praise crazy. Praise sad.

Praise the path on which we’re led.

Praise the roads on earth and water.

Praise the eater and the eaten.

Praise beginnings; praise the end.

Praise the song and praise the singer.

This was my first introduction to Joy Harjo, who has recently been reappointed a second term as the U.S. Poet Laureate. It was posted on an account called The On Being Project, created and led by Krista Tippett, who might be most familiar as host of the On Being podcast. She excerpted Harjo’s poem, “Praise the Rain,” as a promotion for what was then the most recent episode of her latest podcast project hosted by Irish poet Pádraig Ó Tuama, Poetry Unbound. A meditation on the spiritual nature of gratitude and of scrupulous attention (in another line, she says we ought to praise the “curl of plant”), Harjo’s poem was a perfect antidote to both my own mindlessness and the chaos that inspired it. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

It’s a peculiarity of the wine community that when designating the highest quality, we sometimes refer to a score assigned by a critic. But that tells us how much that critic liked the wine in comparison to similar wines. It doesn’t tell us why it deserves such a rating. We have criteria to judge wine quality such as complexity, intensity, balance, and focus. But these refer to various dimensions of a wine, not an overall judgement of quality.

Although most wines provide pleasure, some wines are not merely pleasurable. They stand out from the ordinary and have a special claim on our attention. We need a way of describing the depth and meaning of that experience. In the history of aesthetics “beauty” has filled this role as an indicator of remarkable aesthetic quality. It is less frequently used today than in centuries past since many works of modern or contemporary art do not aim at aesthetic pleasure. After the disruptions of 20th Century art, it seems most people in the art world are disillusioned by beauty as if it were a fusty old term genuflecting toward conventions left behind, something false or inflated that reflective people no longer believe in. Read more »

Patrick Heller in The Hindu:

Patrick Heller in The Hindu:

The global coronavirus pandemic is a natural, albeit brutal experiment. Just about every part of the world has been impacted and the range of responses we are seeing at the national and subnational levels reveal not only existing inequalities but also the political and institutional capacity of governments to respond. Nowhere is this more so true than in India. The national government ordered a lockdown but it is States that are actually implementing measures, both in containing the spread and addressing the welfare consequences of the lockdown. A number of States have been especially proactive, none more so than Kerala.

Flattening the curve and how

Though Kerala was the first State with a recorded case of coronavirus and once led the country in active cases, it now ranks 10th of all States and the total number of active cases (in a State that has done the most aggressive testing in India) has been declining for over a week and is now below the number of recovered cases. Given Kerala’s population density, deep connections to the global economy and the high international mobility of its citizens, it was primed to be a hotspot. Yet not only has the State flattened the curve but it also rolled out a comprehensive ₹20,000 crore economic package before the Centre even declared the lockdown. Why does Kerala stand out in India and internationally?

More here.

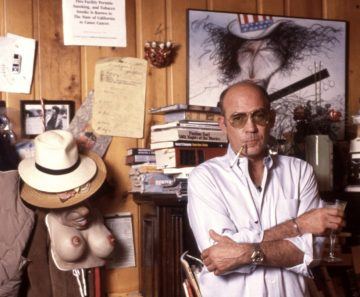

David S. Wills in Quillette:

Fifty years ago today, Hunter S. Thompson and Ralph Steadman drunkenly negotiated the pitfalls of Louisville’s Churchill Downs, home of the world-famous Kentucky Derby. At the time, Thompson was a moderately successful writer who had published an acclaimed book a few years earlier about his time among the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang. Steadman was a talented young artist from Wales who had traveled to the United States in search of work.

For Steadman and Thompson, it would be their first meeting, but it was hardly Thompson’s first derby. He had grown up in Louisville’s Cherokee Park area and was familiar with the whisky gentry who would be in attendance. As a teenager, Thompson’s wit, charm, intellect, and surly insubordination had made him popular among the city’s wealthy young men and women. However, he had never felt fully accepted and, when he was arrested along with a couple of classmates for holding up a car just shy of his graduation, his rich friends abandoned him to his fate—two months in prison.

More here.

Michael Schulson in Undark:

Over the past two decades, John Ioannidis, a professor of medicine, epidemiology, and population health at Stanford University, has gained a reputation as a widely respected gadfly of global science. His work consistently highlights flaws in research methods, pushing scientists and physicians to be more rigorous in evaluating and applying evidence. Ioannidis’ most famous paper, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False,” has been downloaded millions of times and cited in thousands of other studies since its publication in 2005. A 2010 profile in The Atlantic stated that “Ioannidis may be one of the most influential scientists alive.”

Over the past two decades, John Ioannidis, a professor of medicine, epidemiology, and population health at Stanford University, has gained a reputation as a widely respected gadfly of global science. His work consistently highlights flaws in research methods, pushing scientists and physicians to be more rigorous in evaluating and applying evidence. Ioannidis’ most famous paper, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False,” has been downloaded millions of times and cited in thousands of other studies since its publication in 2005. A 2010 profile in The Atlantic stated that “Ioannidis may be one of the most influential scientists alive.”

Ioannidis’ latest work, though, has sparked pushback from many of his colleagues, with some suggesting that the researcher may be succumbing to the very sloppiness he has spent his career fighting. Since mid-March, Ioannidis has been arguing that the fatality rate of Covid-19 may be much lower than initially feared — and that, as a result, current public health restrictions could be overly strict. Last week, a Stanford-led study of Covid-19 infection rates in Santa Clara County, California, which lists Ioannidis as an author, seemed to offer some of the most forceful backing for that argument. The paper suggests that the fatality rate for Covid-19 may be 0.2 percent or less — lower than many other estimates, and much closer to the seasonal flu.

These arguments have earned Ioannidis widespread attention in conservative media, where many commentators are skeptical of the overall risk of Covid-19, and critical of the restrictions currently in place across much of the world.

In the past week, though, the Stanford study, and a related effort in Los Angeles, have come under fierce criticism from prominent statisticians and infectious disease experts.

More here.

Leanne Ogasawara in the Dublin Review of Books:

A bewildering beginning. A German man has a dream that his wife is cheating on him. He wakes up enraged and boards a flight to Tokyo. Why? He has no idea. Arriving in Tokyo, he encounters a young man trying to commit suicide. The German man, Gilbert Silvester, is an adjunct professor, specialising in the religious significance of beards in art and film. Because of his occupation, he can’t help but notice the young man standing precariously on the edge of the train station platform ‑ not because the young man seems in peril but because he has prominent facial hair, something Gilbert did not expect to find in Japan. Striking up a conversation, he learns that the young man is trying to commit suicide. To distract him, Gilbert suggests a trip to find a more poetic place to die. And so, this odd couple embark on a journey north to Matsushima.

A bewildering beginning. A German man has a dream that his wife is cheating on him. He wakes up enraged and boards a flight to Tokyo. Why? He has no idea. Arriving in Tokyo, he encounters a young man trying to commit suicide. The German man, Gilbert Silvester, is an adjunct professor, specialising in the religious significance of beards in art and film. Because of his occupation, he can’t help but notice the young man standing precariously on the edge of the train station platform ‑ not because the young man seems in peril but because he has prominent facial hair, something Gilbert did not expect to find in Japan. Striking up a conversation, he learns that the young man is trying to commit suicide. To distract him, Gilbert suggests a trip to find a more poetic place to die. And so, this odd couple embark on a journey north to Matsushima.

People in Japan go to Matsushima for the scenery. Oysters too. But mostly it’s for the scenery. Countless pine-clad islands scattered around the bay make for an unforgettable sight. No less a figure than Matsuo Basho set off on his famous trip, recounted in The Narrow Road to the Deep North, because he “could hardly think of anything else but seeing the moon over Matsushima”. Basho travelled to Matsushima with his trusty companion Sora, much as Gilbert travels with Yosa Tomagotchi, the suicidal youth.

More here.

Anne Applebaum in The Atlantic:

Propaganda also works best in a vacuum, when there are no competing messages, or when the available alternative messengers inspire no trust. Since mid-March, China has been sending messages out into precisely this kind of vacuum: a world that has been profoundly changed not just by the virus, but by the American president’s simultaneously catastrophic and ridiculous failure to cope with it. The tone of news headlines ranges from straight-faced in Kompas, a major Indonesian news outlet—Trump Usulkan Suntik Disinfektan dan Sinar UV untuk Obati Covid-19, or “Trump Proposes Disinfectant Injection and UV Rays to Treat COVID-19”—to snide, from Le Monde in France—Les élucubrations du « docteur » Trump, or “The Rantings of ‘Doctor’ Trump.” The incredulous first paragraph of an article in Sowetan, from South Africa, declares that “US President Donald Trump has again left people stunned and confused with his bizarre suggestion that disinfectant and ultraviolet light could possibly be used to treat Covid-19.” El Comercio, a distinguished Peruvian newspaper, treated its readers to photographs of Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus-response coordinator, grimacing as the president asked her whether the injection of disinfectant might be a cure.

Propaganda also works best in a vacuum, when there are no competing messages, or when the available alternative messengers inspire no trust. Since mid-March, China has been sending messages out into precisely this kind of vacuum: a world that has been profoundly changed not just by the virus, but by the American president’s simultaneously catastrophic and ridiculous failure to cope with it. The tone of news headlines ranges from straight-faced in Kompas, a major Indonesian news outlet—Trump Usulkan Suntik Disinfektan dan Sinar UV untuk Obati Covid-19, or “Trump Proposes Disinfectant Injection and UV Rays to Treat COVID-19”—to snide, from Le Monde in France—Les élucubrations du « docteur » Trump, or “The Rantings of ‘Doctor’ Trump.” The incredulous first paragraph of an article in Sowetan, from South Africa, declares that “US President Donald Trump has again left people stunned and confused with his bizarre suggestion that disinfectant and ultraviolet light could possibly be used to treat Covid-19.” El Comercio, a distinguished Peruvian newspaper, treated its readers to photographs of Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus-response coordinator, grimacing as the president asked her whether the injection of disinfectant might be a cure.

Quotations from the president’s astonishing April 23 press conference have appeared on every continent, via countless television channels, radio stations, magazines, and websites, in hundreds of thousands of variations and dozens of languages—often accompanied by warnings, in case someone was fooled, not to drink disinfectant or bleach. In years past, many of these outlets presumably published articles critical of this or that aspect of U.S. foreign policy, blaming one U.S. president or another. But the kind of coverage we see now is something new. This time, people are not attacking the president of the United States. They are laughing at him. Beppe Severgnini, one of Italy’s best-known columnists, told me that while Italians feel enormous empathy for Americans who have suffered as they have, they feel differently about Trump: “In this time of darkness and depression, he keeps us entertained.”

But if Trump is ridiculous, his administration is invisible.

More here.

Yuval Noah Harari in The Guardian:

The modern world has been shaped by the belief that humans can outsmart and defeat death. That was a revolutionary new attitude. For most of history, humans meekly submitted to death. Up to the late modern age, most religions and ideologies saw death not only as our inevitable fate, but as the main source of meaning in life. The most important events of human existence happened after you exhaled your last breath. Only then did you come to learn the true secrets of life. Only then did you gain eternal salvation, or suffer everlasting damnation. In a world without death – and therefore without heaven, hell or reincarnation – religions such as Christianity, Islam and Hinduism would have made no sense. For most of history the best human minds were busy giving meaning to death, not trying to defeat it. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, the Bible, the Qur’an, the Vedas, and countless other sacred books and tales patiently explained to distressed humans that we die because God decreed it, or the Cosmos, or Mother Nature, and we had better accept that destiny with humility and grace. Perhaps someday God would abolish death through a grand metaphysical gesture such as Christ’s second coming. But orchestrating such cataclysms was clearly above the pay grade of flesh-and-blood humans.

The modern world has been shaped by the belief that humans can outsmart and defeat death. That was a revolutionary new attitude. For most of history, humans meekly submitted to death. Up to the late modern age, most religions and ideologies saw death not only as our inevitable fate, but as the main source of meaning in life. The most important events of human existence happened after you exhaled your last breath. Only then did you come to learn the true secrets of life. Only then did you gain eternal salvation, or suffer everlasting damnation. In a world without death – and therefore without heaven, hell or reincarnation – religions such as Christianity, Islam and Hinduism would have made no sense. For most of history the best human minds were busy giving meaning to death, not trying to defeat it. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, the Bible, the Qur’an, the Vedas, and countless other sacred books and tales patiently explained to distressed humans that we die because God decreed it, or the Cosmos, or Mother Nature, and we had better accept that destiny with humility and grace. Perhaps someday God would abolish death through a grand metaphysical gesture such as Christ’s second coming. But orchestrating such cataclysms was clearly above the pay grade of flesh-and-blood humans.

Then came the scientific revolution. For scientists, death isn’t a divine decree – it is merely a technical problem. Humans die not because God said so, but because of some technical glitch. The heart stops pumping blood. Cancer has destroyed the liver. Viruses multiply in the lungs. And what is responsible for all these technical problems? Other technical problems. The heart stops pumping blood because not enough oxygen reaches the heart muscle. Cancerous cells spread in the liver because of some chance genetic mutation. Viruses settled in my lungs because somebody sneezed on the bus. Nothing metaphysical about it.

And science believes that every technical problem has a technical solution. We don’t need to wait for Christ’s second coming in order to overcome death. A couple of scientists in a lab can do it. Whereas traditionally death was the speciality of priests and theologians in black cassocks, now it’s the folks in white lab coats. If the heart flutters, we can stimulate it with a pacemaker or even transplant a new heart. If cancer rampages, we can kill it with radiation. If viruses proliferate in the lungs, we can subdue them with some new medicine.

True, at present we cannot solve all technical problems. But we are working on them. The best human minds no longer spend their time trying to give meaning to death. Instead, they are busy extending life.

More here.

Narcissus, I no longer haunt the canyons

and the crypts. I thrive and multiply;

uncounted daughters are my new companions.

We are the voicemail’s ponderous reply

to the computers making random calls.

We are the Muzak in the empty malls,

the laughtrack on the reruns late at night,

the distant siren’s chilling lullaby,

the steady chirp of things that simplify

their scheduled lives. You know I could recite

more, but you never cared for my recitals.

I do not miss you, do not need you here —

I can repeat the words of your disciples

telling lovers what they want to hear.

A.M. Juster

from A.M. Juster.net

Linda Heuman in Tricycle:

When the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi announced to his parents, secular Hindus, that he planned to convert to Buddhism and ordain as a monk, his father convened 76 members of his extended family to discuss the matter. Over several hours his relatives plied him with questions, an ordeal Priyadarshi calls “trial by family” in his memoir, Running Toward Mystery: The Adventure of an Unconventional Life, coauthored by Zara Houshmand. To understand his parents’ severe reaction, it helps to know that at the time of the interrogation Priyadarshi was only 10 years old. He had just run away from boarding school in West Bengal, India, and vanished without a trace. His family had spent two anguished weeks trying to locate him and finally tracked him down at a Japanese Buddhist temple in Bihar, nearly 300 kilometers from the school where he was supposed to be. At that moment, they were not feeling very sympathetic.

When the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi announced to his parents, secular Hindus, that he planned to convert to Buddhism and ordain as a monk, his father convened 76 members of his extended family to discuss the matter. Over several hours his relatives plied him with questions, an ordeal Priyadarshi calls “trial by family” in his memoir, Running Toward Mystery: The Adventure of an Unconventional Life, coauthored by Zara Houshmand. To understand his parents’ severe reaction, it helps to know that at the time of the interrogation Priyadarshi was only 10 years old. He had just run away from boarding school in West Bengal, India, and vanished without a trace. His family had spent two anguished weeks trying to locate him and finally tracked him down at a Japanese Buddhist temple in Bihar, nearly 300 kilometers from the school where he was supposed to be. At that moment, they were not feeling very sympathetic.

The members of Priyadarshi’s clan were familiar with spiritual seekers— this was India—but these were modern, educated, and secular Brahmins. One stated flatly, “Full-time religion is what people do when they have no education, no prospects, no other way to survive.”

More here.

Nouriel Roubini in The Guardian:

Nouriel Roubini in The Guardian:

A fifth issue is the broader digital disruption of the economy. With millions of people losing their jobs or working and earning less, the income and wealth gaps of the 21st-century economy will widen further. To guard against future supply-chain shocks, companies in advanced economies will re-shore production from low-cost regions to higher-cost domestic markets. But rather than helping workers at home, this trend will accelerate the pace of automation, putting downward pressure on wages and further fanning the flames of populism, nationalism, and xenophobia.

This points to the sixth major factor: deglobalisation. The pandemic is accelerating trends toward balkanisation and fragmentation that were already well underway. The US and China will decouple faster, and most countries will respond by adopting still more protectionist policies to shield domestic firms and workers from global disruptions. The post-pandemic world will be marked by tighter restrictions on the movement of goods, services, capital, labour, technology, data, and information. This is already happening in the pharmaceutical, medical-equipment, and food sectors, where governments are imposing export restrictions and other protectionist measures in response to the crisis.

The backlash against democracy will reinforce this trend.

More here.

Sonya Aragon in n+1:

Sonya Aragon in n+1:

ONE OF THE LAST TIMES I saw a client in person, before New York City’s now-hardened shelter-in-place order, we met in an oddly decorated hotel room in downtown Brooklyn. It was our second meeting, but I had the keen sense that he would become a regular. This, because following our first meeting, we had begun the complicated dance of declaring our feelings—our “connection”—as being out of the ordinary for the transactional circumstances that brought us together. And this was true, to a degree, for me. At our first meeting, I’d earnestly wanted him, something I had never felt with a client prior. He was young and tattooed, a former anarchist punk. He still went to shows sometimes, he said; based on his description of a new DIY space, it seemed like we had attended the same benefit a couple months back. (My boyfriend had been convinced that the bottle of tequila he passed around that show, a bottle that, unimaginably now, twenty people must have sipped from, was ground zero for the flu we all caught in December—the one everyone retroactively seems to think was Covid, despite the improbability.) I liked the idea that someone I could have met as me—a me without the pretense of a different, more appealing me—was paying me, and I liked tracing the skulls and knives on his chest with my fingers, and I liked his implied antipathy toward authority, even if it seemed like he was probably aging into a quieter liberalism.

More here.