by Sarah Firisen

Many years ago in 1991, in my first job out of college, I worked for a small investment bank. By 1994, I was working in its IT department. One of my tasks was PC support and I had a modem attached to my computer so that I could connect to Compuserve for research on technical issues. Yes, this was the heydey of Compuserve, the year that the first web browser came out and a time when most people had very little idea, if any, what this Internet thing was.

Many years ago in 1991, in my first job out of college, I worked for a small investment bank. By 1994, I was working in its IT department. One of my tasks was PC support and I had a modem attached to my computer so that I could connect to Compuserve for research on technical issues. Yes, this was the heydey of Compuserve, the year that the first web browser came out and a time when most people had very little idea, if any, what this Internet thing was.

As a tech geek, I signed up for one of the early, local Internet Service Providers and had an email account on their Unix based system. I actually met my now ex-husband through that email account, which is a whole other story. During this period, the ex and I were just starting our email correspondence and I would dial into my ISP at work to check my email. At some point, these minimal phone charges came to the attention of the firm’s Managing Director who took me aside and asked what I was doing. I told him about this wonderful new thing, the Internet! He told me to stop using the company’s modem to connect to anything but Compuserve. I protested, somewhat, and tried to tell him what a wonderful innovation the Internet was (and bear in mind, at the time, there weren’t a lot of websites and they loaded incredibly slowly, so even a geek had to use some imagination to see the future possibilities). He told me that the company would not be doing anything with the Internet anytime in the future. And by the way, this is a company who had already made a lot of its money from deals and IPOs in the entertainment and technology sector, so that they might have been interested in what I had to say wasn’t an outrageous idea.

Suffice it to say, that Managing Director was wrong and over the years that investment bank has been involved in many of the most significant deals with some of the biggest Internet-related companies. So what was the missed opportunity there? Clearly, that Managing Director was no visionary but my old company also ended up doing just fine and caught onto the Internet early enough to make a lot of money anyway. But, how much more money could they have made if someone had listened to me back then? I was young and very junior at the company and felt ashamed to have been “caught” and told off. But in hindsight, what I could have done was tell him a better story about this new, disruptive technology. Read more »

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there. In the fall of 1971, I set out from the small New Hampshire town where I’d spent the first 17 years of my life and rode a Greyhound bus to New Haven. I had a trunk of clothes, a portable stereo housed in a red Samsonite suitcase, and a couple dozen vinyl albums—Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, the Rolling Stones—that I hauled up three flights of stairs to a fourth-floor dormitory room. Yale had gone coed two years before, but ours was the first class in which women would complete the full four years.

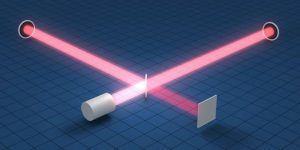

In the fall of 1971, I set out from the small New Hampshire town where I’d spent the first 17 years of my life and rode a Greyhound bus to New Haven. I had a trunk of clothes, a portable stereo housed in a red Samsonite suitcase, and a couple dozen vinyl albums—Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, the Rolling Stones—that I hauled up three flights of stairs to a fourth-floor dormitory room. Yale had gone coed two years before, but ours was the first class in which women would complete the full four years. Light always moves at the same, constant speed: c, or 299,792,458 m/s. That’s the speed of light in a vacuum, and LIGO has vacuum chambers inside both arms. The thing is, when a gravitational wave passes through each arm, lengthening or shortening the arm, it also lengthens or shortens the wavelength of the light within it by a corresponding amount.

Light always moves at the same, constant speed: c, or 299,792,458 m/s. That’s the speed of light in a vacuum, and LIGO has vacuum chambers inside both arms. The thing is, when a gravitational wave passes through each arm, lengthening or shortening the arm, it also lengthens or shortens the wavelength of the light within it by a corresponding amount. After the crash of 2008, the language of inequality began to trickle into the popular discourse. Then the Occupy movement launched it into the mainstream; the fall of 2011 was the first time in generations that concerns about distributive justice drove crowds into the streets and made front-page news. Scholars, pundits, and politicians all took note, and before long, Gornick and her colleagues found themselves at the center of what President Barack Obama

After the crash of 2008, the language of inequality began to trickle into the popular discourse. Then the Occupy movement launched it into the mainstream; the fall of 2011 was the first time in generations that concerns about distributive justice drove crowds into the streets and made front-page news. Scholars, pundits, and politicians all took note, and before long, Gornick and her colleagues found themselves at the center of what President Barack Obama  In his appearance before the Senate Judiciary Committee last week, Brett Kavanaugh put on a prodigious display of vacuity and mendacity. Kavanaugh is the retrograde jurist picked by Donald Trump to fill the Supreme Court vacancy that arose when the Court’s “swing vote,” Anthony Kennedy, retired. His politics is god awful, but that is hardly news. It was a sure thing that Trump would nominate someone with god-awful politics. Because he knows little and cares less about the judicial system, except when it impinges on his financial shenanigans, and because, as part of his pact with “conservatives” Trump outsourced judicial appointments to the Federalist Society, anyone he would nominate was bound to come with god-awful politics. At least, this particular god-awful jurist is well schooled, well spoken (in the way that lawyers are), and intelligent enough to talk like a lawyer or judge, while dissembling shamelessly and saying nothing of substance. That puts him leagues ahead of Trump. It also puts him head and shoulders above the average Republican. But let’s not praise him too much on that account; much the same could be said of Ted Cruz. Because politically the two of them are so much alike, it is instructive to compare Kavanaugh with that villainous Texas Senator.

In his appearance before the Senate Judiciary Committee last week, Brett Kavanaugh put on a prodigious display of vacuity and mendacity. Kavanaugh is the retrograde jurist picked by Donald Trump to fill the Supreme Court vacancy that arose when the Court’s “swing vote,” Anthony Kennedy, retired. His politics is god awful, but that is hardly news. It was a sure thing that Trump would nominate someone with god-awful politics. Because he knows little and cares less about the judicial system, except when it impinges on his financial shenanigans, and because, as part of his pact with “conservatives” Trump outsourced judicial appointments to the Federalist Society, anyone he would nominate was bound to come with god-awful politics. At least, this particular god-awful jurist is well schooled, well spoken (in the way that lawyers are), and intelligent enough to talk like a lawyer or judge, while dissembling shamelessly and saying nothing of substance. That puts him leagues ahead of Trump. It also puts him head and shoulders above the average Republican. But let’s not praise him too much on that account; much the same could be said of Ted Cruz. Because politically the two of them are so much alike, it is instructive to compare Kavanaugh with that villainous Texas Senator. How can arts respond to conflict, human rights violations and impunity? What role can they play in peace building and reconciliation? These questions are raised by Milo Rau’s Congo Tribunal, a multimedia project, consisting of a film, a book, a website, a 3D installation, an exhibition in The Hague and, most centrally, a performance that took place in Bukavu and Berlin. The project has an ambitious bottomline: “where politics fail, only art can take over.” The failure of politics, in this case, lie in the blatant impunity and perpetuation of the violence that engulfs eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since more than twenty years. Milo Rau is very explicit in his political aims,

How can arts respond to conflict, human rights violations and impunity? What role can they play in peace building and reconciliation? These questions are raised by Milo Rau’s Congo Tribunal, a multimedia project, consisting of a film, a book, a website, a 3D installation, an exhibition in The Hague and, most centrally, a performance that took place in Bukavu and Berlin. The project has an ambitious bottomline: “where politics fail, only art can take over.” The failure of politics, in this case, lie in the blatant impunity and perpetuation of the violence that engulfs eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since more than twenty years. Milo Rau is very explicit in his political aims,  On the Other Side of Freedom is filled with short bursts of this kind of beauty. In service of what, though? In twelve chapters covering organizing, identity, activism, and more, Mckesson sets out to provide an “intellectual, pragmatic political framework for a new liberation movement.”But he doesn’t move much beyond poetic rhapsodizing about protest, which he romanticizes to the exclusion of most other aspects of resistance. Indeed, he’s outright dismissive of some. In the chapter “On Organizing,” he recounts his frustrations at a training session led by a national organizer, which wasn’t, he felt, useful to the situation in Ferguson. This could have been a great opportunity to describe new directions that activism might take, but his description of the meeting’s shortcomings are frustratingly vague. He is unhappy with the notion of the “top-down model in which an organizing body or institution confers knowledge, gives direction, grants permission.” The protesters, he points out, don’t need this kind of guidance—they already possess the skills necessary for effective activism. “The tactics that were effective in bringing about change in the sixties, seventies, and eighties are well known to all,” he explains. “And thus we needed new tactics for a new time.” And what are those new tactics? “To ignore the role of social media as difference-maker in organizing is perilous.”

On the Other Side of Freedom is filled with short bursts of this kind of beauty. In service of what, though? In twelve chapters covering organizing, identity, activism, and more, Mckesson sets out to provide an “intellectual, pragmatic political framework for a new liberation movement.”But he doesn’t move much beyond poetic rhapsodizing about protest, which he romanticizes to the exclusion of most other aspects of resistance. Indeed, he’s outright dismissive of some. In the chapter “On Organizing,” he recounts his frustrations at a training session led by a national organizer, which wasn’t, he felt, useful to the situation in Ferguson. This could have been a great opportunity to describe new directions that activism might take, but his description of the meeting’s shortcomings are frustratingly vague. He is unhappy with the notion of the “top-down model in which an organizing body or institution confers knowledge, gives direction, grants permission.” The protesters, he points out, don’t need this kind of guidance—they already possess the skills necessary for effective activism. “The tactics that were effective in bringing about change in the sixties, seventies, and eighties are well known to all,” he explains. “And thus we needed new tactics for a new time.” And what are those new tactics? “To ignore the role of social media as difference-maker in organizing is perilous.” [Bob] Woodward has never been a very good writer, but his literary failures have never been more apparent than in Fear, where the mismatch between the prose and the protagonists is almost avant-garde. Many sentences are overwrought to the point of being nonsensical. (“The first act of the Bannon drama is his appearance—the old military field jacket over multiple tennis polo shirts. The second act is his demeanor—aggressive, certain and loud.”) His reliance on cliché is laughable, particularly in his descriptions of characters with whom all of the book’s readers are already well-acquainted. Kellyanne Conway is “feisty” and Reince Priebus—a source whom Woodward conspicuously flatters—is an “empire builder.” Mohammed bin Salman is “charming” and has “vision, energy,” which suggests Woodward has been reading Tom Friedman columns. Jared Kushner has a “self-possessed, almost aristocratic bearing” (possibly the most self-evidently false detail in a book full of them). And the late John McCain is (of course) “outspoken” and a “maverick.” Woodward seems to have a fascination with the bodies and demeanor of older, military men: both Jim Mattis and H.R. McMaster have “ramrod-straight posture,” and the latter is described as “high and tight,” even though he is conspicuously bald. Trump goes “through the roof” twice in a single chapter. And so on.

[Bob] Woodward has never been a very good writer, but his literary failures have never been more apparent than in Fear, where the mismatch between the prose and the protagonists is almost avant-garde. Many sentences are overwrought to the point of being nonsensical. (“The first act of the Bannon drama is his appearance—the old military field jacket over multiple tennis polo shirts. The second act is his demeanor—aggressive, certain and loud.”) His reliance on cliché is laughable, particularly in his descriptions of characters with whom all of the book’s readers are already well-acquainted. Kellyanne Conway is “feisty” and Reince Priebus—a source whom Woodward conspicuously flatters—is an “empire builder.” Mohammed bin Salman is “charming” and has “vision, energy,” which suggests Woodward has been reading Tom Friedman columns. Jared Kushner has a “self-possessed, almost aristocratic bearing” (possibly the most self-evidently false detail in a book full of them). And the late John McCain is (of course) “outspoken” and a “maverick.” Woodward seems to have a fascination with the bodies and demeanor of older, military men: both Jim Mattis and H.R. McMaster have “ramrod-straight posture,” and the latter is described as “high and tight,” even though he is conspicuously bald. Trump goes “through the roof” twice in a single chapter. And so on. One week last month, when it was unseasonably cold and rainy—which I loved because I was in a depression—there were suddenly mice flurrying everywhere in the courtyard, in and out of a pneumatic HVAC unit they installed last summer. The mice seemed extra small. Maybe they were babies. Maybe it was because two summers ago we had raccoons in the yard. Then last summer, rats, and a few roaches.

One week last month, when it was unseasonably cold and rainy—which I loved because I was in a depression—there were suddenly mice flurrying everywhere in the courtyard, in and out of a pneumatic HVAC unit they installed last summer. The mice seemed extra small. Maybe they were babies. Maybe it was because two summers ago we had raccoons in the yard. Then last summer, rats, and a few roaches. Norman Ernest Borlaug was an American agronomist and humanitarian born in Iowa in 1914. After receiving a PhD from the University of Minnesota in 1944, Borlaug moved to Mexico to work on agricultural development for the Rockefeller Foundation. Although Borlaug’s taskforce was initiated to teach Mexican farmers methods to increase food productivity, he quickly became obsessed with developing better (i.e., higher-yielding and pest-and-climate resistant) crops.

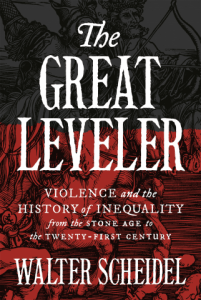

Norman Ernest Borlaug was an American agronomist and humanitarian born in Iowa in 1914. After receiving a PhD from the University of Minnesota in 1944, Borlaug moved to Mexico to work on agricultural development for the Rockefeller Foundation. Although Borlaug’s taskforce was initiated to teach Mexican farmers methods to increase food productivity, he quickly became obsessed with developing better (i.e., higher-yielding and pest-and-climate resistant) crops. In an age of widening inequality, Walter Scheidel believes he has cracked the code on how to overcome it. In “The Great Leveler”, the Stanford professor posits that throughout history, economic inequality has only been rectified by one of the “Four Horsemen of Leveling”: warfare, revolution, state collapse and plague.

In an age of widening inequality, Walter Scheidel believes he has cracked the code on how to overcome it. In “The Great Leveler”, the Stanford professor posits that throughout history, economic inequality has only been rectified by one of the “Four Horsemen of Leveling”: warfare, revolution, state collapse and plague. So he sets off, offering the things Sinclair fans will know well: the rhythms of urban walks that turn into sentences and paragraphs, the tracing and retracing of old and new ground, the eternal return to the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor that he has been performing since his Lud Heat of 1975, long before Peter Ackroyd got in on the act. Also the cadences of mordancy and mortality, the attraction to putrefaction. The streets and walls of Sinclair City have the odour and texture of things found floating on canals, but are iridescent with unexpected beauty.

So he sets off, offering the things Sinclair fans will know well: the rhythms of urban walks that turn into sentences and paragraphs, the tracing and retracing of old and new ground, the eternal return to the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor that he has been performing since his Lud Heat of 1975, long before Peter Ackroyd got in on the act. Also the cadences of mordancy and mortality, the attraction to putrefaction. The streets and walls of Sinclair City have the odour and texture of things found floating on canals, but are iridescent with unexpected beauty.