Tim Martin in New Statesman:

Seventy-five years ago, in April 1943, the research chemist Albert Hofmann did something distinctly out of scientific character. Impelled by what he later called a “peculiar presentiment”, he resolved to take a second look at the 25th in a series of molecules derived from the ergot fungus, a drug he had discovered some years earlier and dismissed as of no scientific interest. As he synthesised it for the second time, it made contact with his skin, giving rise to an unprecedented experience: a “stream of fantastic pictures [and] extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colours”. Five days later, on 19 April, he decided to test the chemical on himself under controlled conditions, thus becoming the first person in history knowingly to embark on an acid trip.

Seventy-five years ago, in April 1943, the research chemist Albert Hofmann did something distinctly out of scientific character. Impelled by what he later called a “peculiar presentiment”, he resolved to take a second look at the 25th in a series of molecules derived from the ergot fungus, a drug he had discovered some years earlier and dismissed as of no scientific interest. As he synthesised it for the second time, it made contact with his skin, giving rise to an unprecedented experience: a “stream of fantastic pictures [and] extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colours”. Five days later, on 19 April, he decided to test the chemical on himself under controlled conditions, thus becoming the first person in history knowingly to embark on an acid trip.

Intermittently ever since, psychonauts and countercultural enthusiasts have celebrated 19 April as “Bicycle Day”, in recognition of this Ground Zero of Western psychedelia. After cautiously ingesting a dose of LSD-25, Hofmann enlisted the help of a lab assistant and wobbled home on his bicycle, while his vision “wavered and distorted as though in a curved mirror”. Sprawled on the sofa, he underwent a “severe crisis” that, viewed through the telescope of 75 years of psychedelic experience, looks endearingly familiar: one in which demonic terrors, mystical encounters and loss of ego alternated with fantastic imagery, synaesthetic perception and a desire to drink “more than two litres” of the milk provided by a neighbour. This year, however, those celebrating Bicycle Day did so against a new background. After decades in the shadow of the 1960s counterculture, psychedelic drugs have emerged once again into the light of scientific orthodoxy. Researchers at major universities – Johns Hopkins in the US, Imperial College in London – have, over the past 20 years, been conducting experiments at growing scale to assess the effects of substances such as LSD, MDMA and psilocybin, the psychedelic compound in magic mushrooms. Their results suggest that these powerful molecules, long stigmatised as drugs of self-gratification or abuse, may instead be miracle treatments for the most intractable disorders of our time: depression, isolation, addiction and post-traumatic stress.

More here.

The storms of rivalry and feud currently blowing through America’s internet portals rise to the wind-scale force of Wagnerian opera, but it’s hard to know whether the sound and fury is personal, political, or pathological. The stagings of vengeful lies to destroy a graven Facebook image, or the voicing of competitive truth that is the vitality of a democratic republic? The problem doesn’t yield to zero-sum solution.

The storms of rivalry and feud currently blowing through America’s internet portals rise to the wind-scale force of Wagnerian opera, but it’s hard to know whether the sound and fury is personal, political, or pathological. The stagings of vengeful lies to destroy a graven Facebook image, or the voicing of competitive truth that is the vitality of a democratic republic? The problem doesn’t yield to zero-sum solution.  Recent primaries have given Democrats reasons for hope, but they have also exposed fault lines within the party. Divisions are visible in the very labels used to describe them. Many use the word “liberal” as a catchall to describe left-of-center politics in general, but self-described leftists and members of the Democratic Socialists of America often characterize liberals and Democrats as their opponents—viewing them as the compromising centrists standing in the way of a more progressive or socialist agenda.

Recent primaries have given Democrats reasons for hope, but they have also exposed fault lines within the party. Divisions are visible in the very labels used to describe them. Many use the word “liberal” as a catchall to describe left-of-center politics in general, but self-described leftists and members of the Democratic Socialists of America often characterize liberals and Democrats as their opponents—viewing them as the compromising centrists standing in the way of a more progressive or socialist agenda. Psychologists are in the midst of an ongoing, difficult reckoning. Many believe that their field is experiencing a “

Psychologists are in the midst of an ongoing, difficult reckoning. Many believe that their field is experiencing a “ The dead books are on the top floor of Southern Methodist University’s law library.

The dead books are on the top floor of Southern Methodist University’s law library. In 1969 the painter Jack Whitten arrived in the town of Agia Galini, on the Greek island of Crete. Shortly before leaving New York he’d had a dream in which he was commanded to find a tree and carve it. From the bus window he spied the tree from his dream. He approached the owner, but because Whitten couldn’t speak Greek, the man thought he was saying he wanted to cut it down. Whitten came up with a plan to communicate his aim: “I went into the surrounding hills, found some wood and set up shop on the harbor beneath some trees.” The owner understood immediately and even lent Whitten his tools. The totem he carved still stands in the town—a fisherman looks to the sea, an octopus winds around the trunk, and at the very top “is a large fish with its tail pointing to the sky.” This account, published in Notes from the Woodshed, a volume of the artist’s reflections on his art and practice, provides a key to understanding the gestural, communicative power of Whitten’s sculpture. Just as he was able to impart meaning by doing rather than speaking that first day on Crete, his sculptures—currently exhibited for the first time in a show that has arrived at the Met Breuer (New York)—express their strong emotional and spiritual content by foregrounding the physical acts of their creation. Carved, chiseled, polished, and hammered into insinuating, assertive shapes, these pieces make viewers feel the actual work, and sense the very grip of the artist’s hand on the hammer as it finds the chisel’s head.

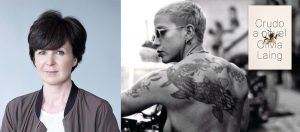

In 1969 the painter Jack Whitten arrived in the town of Agia Galini, on the Greek island of Crete. Shortly before leaving New York he’d had a dream in which he was commanded to find a tree and carve it. From the bus window he spied the tree from his dream. He approached the owner, but because Whitten couldn’t speak Greek, the man thought he was saying he wanted to cut it down. Whitten came up with a plan to communicate his aim: “I went into the surrounding hills, found some wood and set up shop on the harbor beneath some trees.” The owner understood immediately and even lent Whitten his tools. The totem he carved still stands in the town—a fisherman looks to the sea, an octopus winds around the trunk, and at the very top “is a large fish with its tail pointing to the sky.” This account, published in Notes from the Woodshed, a volume of the artist’s reflections on his art and practice, provides a key to understanding the gestural, communicative power of Whitten’s sculpture. Just as he was able to impart meaning by doing rather than speaking that first day on Crete, his sculptures—currently exhibited for the first time in a show that has arrived at the Met Breuer (New York)—express their strong emotional and spiritual content by foregrounding the physical acts of their creation. Carved, chiseled, polished, and hammered into insinuating, assertive shapes, these pieces make viewers feel the actual work, and sense the very grip of the artist’s hand on the hammer as it finds the chisel’s head. Yes, it was incredibly liberating, both to invent the character and to help myself to the ravishing grab-bag of Acker’s own work. Crudo is probably the only book I’ve really enjoyed writing, because it was so fast and so free. It was such a relief to ditch the I, but to keep all the real details of the world, to collage it together rather than inventing it afresh. I definitely have a horror of making shit up, but I also have a horror of confessional writing. It’s like the case studies in I Love Dick, I do want to write about the personal (mine, Acker’s, David Wojnarowicz’s and so on), but for political reasons.

Yes, it was incredibly liberating, both to invent the character and to help myself to the ravishing grab-bag of Acker’s own work. Crudo is probably the only book I’ve really enjoyed writing, because it was so fast and so free. It was such a relief to ditch the I, but to keep all the real details of the world, to collage it together rather than inventing it afresh. I definitely have a horror of making shit up, but I also have a horror of confessional writing. It’s like the case studies in I Love Dick, I do want to write about the personal (mine, Acker’s, David Wojnarowicz’s and so on), but for political reasons. Democrats may scoff at Republicans’ work requirements, but they have yet to challenge the dominant conception of poverty that feeds such meanspirited politics. Instead of offering a counternarrative to America’s moral trope of deservedness, liberals have generally submitted to it, perhaps even embraced it, figuring that the public will not support aid that doesn’t demand that the poor subject themselves to the low-paying jobs now available to them. Even stalwarts of the progressive movement seem to reserve economic prosperity for the full-time worker. Senator Bernie Sanders once declared, echoing a long line of Democrats who have come before and after him, “Nobody who works 40 hours a week should be living in poverty.” Sure, but what about those who work 20 or 30 hours, like Vanessa?

Democrats may scoff at Republicans’ work requirements, but they have yet to challenge the dominant conception of poverty that feeds such meanspirited politics. Instead of offering a counternarrative to America’s moral trope of deservedness, liberals have generally submitted to it, perhaps even embraced it, figuring that the public will not support aid that doesn’t demand that the poor subject themselves to the low-paying jobs now available to them. Even stalwarts of the progressive movement seem to reserve economic prosperity for the full-time worker. Senator Bernie Sanders once declared, echoing a long line of Democrats who have come before and after him, “Nobody who works 40 hours a week should be living in poverty.” Sure, but what about those who work 20 or 30 hours, like Vanessa?

From bulging biceps to 7-foot wingspans to a striking paucity of fat, elite athletes’ bodies often look quite different from those of the rest of us. But it’s not only athletes’ bodies that are different; their brains are just as finely tuned to the mental demands of a particular sport. Here are seven areas of the brain that enable seven different athletes to pull off extraordinary feats.

From bulging biceps to 7-foot wingspans to a striking paucity of fat, elite athletes’ bodies often look quite different from those of the rest of us. But it’s not only athletes’ bodies that are different; their brains are just as finely tuned to the mental demands of a particular sport. Here are seven areas of the brain that enable seven different athletes to pull off extraordinary feats. In the highly controversial area of human intelligence, the ‘Greater Male Variability Hypothesis’ (GMVH) asserts that there are more idiots and more geniuses among men than among women. Darwin’s research on evolution in the nineteenth century found that, although there are many exceptions for specific traits and species, there is generally more variability in males than in females of the same species throughout the animal kingdom.

In the highly controversial area of human intelligence, the ‘Greater Male Variability Hypothesis’ (GMVH) asserts that there are more idiots and more geniuses among men than among women. Darwin’s research on evolution in the nineteenth century found that, although there are many exceptions for specific traits and species, there is generally more variability in males than in females of the same species throughout the animal kingdom. I was disturbed recently by reading about an incident in which a paper was accepted by the Mathematical Intelligencer and then rejected, after which it was accepted and published online by the New York Journal of Mathematics, where it lasted for three days before disappearing and being replaced by another paper of the same length. The reason for this bizarre sequence of events? The paper concerned the “variability hypothesis”, the idea, apparently backed up by a lot of evidence, that there is a strong tendency for traits that can be measured on a numerical scale to show more variability amongst males than amongst females. I do not know anything about the quality of this evidence, other than that there are many papers that claim to observe greater variation amongst males of one trait or another, so that if you want to make a claim along the lines of “you typically see more males both at the top and the bottom of the scale” then you can back it up with a long list of citations.

I was disturbed recently by reading about an incident in which a paper was accepted by the Mathematical Intelligencer and then rejected, after which it was accepted and published online by the New York Journal of Mathematics, where it lasted for three days before disappearing and being replaced by another paper of the same length. The reason for this bizarre sequence of events? The paper concerned the “variability hypothesis”, the idea, apparently backed up by a lot of evidence, that there is a strong tendency for traits that can be measured on a numerical scale to show more variability amongst males than amongst females. I do not know anything about the quality of this evidence, other than that there are many papers that claim to observe greater variation amongst males of one trait or another, so that if you want to make a claim along the lines of “you typically see more males both at the top and the bottom of the scale” then you can back it up with a long list of citations. For something of such obvious importance, money is kind of mysterious. It can, as Homer Simpson once memorably noted, be exchanged for goods and services. But who decides exactly how many goods/services a given unit of money can buy? And what maintains the social contract that we all agree to go along with it? Technology is changing what money is and how we use it, and Neha Narula is a leader in thinking about where money is going. One much-hyped aspect is the advent of blockchain technology, which has led to cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. We talk about what the blockchain really is, how it enables new kinds of currency, and from a wider perspective whether it can help restore a more individualistic, decentralized Web.

For something of such obvious importance, money is kind of mysterious. It can, as Homer Simpson once memorably noted, be exchanged for goods and services. But who decides exactly how many goods/services a given unit of money can buy? And what maintains the social contract that we all agree to go along with it? Technology is changing what money is and how we use it, and Neha Narula is a leader in thinking about where money is going. One much-hyped aspect is the advent of blockchain technology, which has led to cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. We talk about what the blockchain really is, how it enables new kinds of currency, and from a wider perspective whether it can help restore a more individualistic, decentralized Web. In halls and moods of violent possession, we speak of languages as things we “have.” This mood comes easy when the books are small and green—a Loeb’s fits in the palm like a secret jewel, a perfect bun. Its loose-woven ribbon reminds us the gift is inside, our reading an unwrapping—happy birthday to our most serious, our highest mind. In the early aughts, I was often high haha.

In halls and moods of violent possession, we speak of languages as things we “have.” This mood comes easy when the books are small and green—a Loeb’s fits in the palm like a secret jewel, a perfect bun. Its loose-woven ribbon reminds us the gift is inside, our reading an unwrapping—happy birthday to our most serious, our highest mind. In the early aughts, I was often high haha. GORONGOSA NATIONAL PARK, Mozambique — We are flying in a Bat Hawk aircraft — which may be named for a raptor that preys on bats but looks more like a giant, lime-green dragonfly — and my hair, thanks to the open cockpit, has gone full Phyllis Diller. Scudding above flood plains the color of worn pool table felt and mud flats split like jigsaw puzzles, we dip toward the treetops and see herds of waterbuck scatter with an impatient flash of their bull’s-eye rumps. We are searching for the elusive tuskless elephants of Gorongosa, elephants that naturally lack the magnificent ivory staffs all too tragically coveted by wealthy collectors worldwide. Tuskless elephants

GORONGOSA NATIONAL PARK, Mozambique — We are flying in a Bat Hawk aircraft — which may be named for a raptor that preys on bats but looks more like a giant, lime-green dragonfly — and my hair, thanks to the open cockpit, has gone full Phyllis Diller. Scudding above flood plains the color of worn pool table felt and mud flats split like jigsaw puzzles, we dip toward the treetops and see herds of waterbuck scatter with an impatient flash of their bull’s-eye rumps. We are searching for the elusive tuskless elephants of Gorongosa, elephants that naturally lack the magnificent ivory staffs all too tragically coveted by wealthy collectors worldwide. Tuskless elephants