Andrew Sullivan in The New York Times:

It isn’t until you start reading it that you realize how much we need a book like this one at this particular moment. “These Truths,” by Jill Lepore — a professor at Harvard and a staff writer at The New Yorker — is a one-volume history of the United States, constructed around a traditional narrative, that takes you from the 16th to the 21st century. It tries to take in almost everything, an impossible task, but I’d be hard-pressed to think she could have crammed more into these 932 highly readable pages. It covers the history of political thought, the fabric of American social life over the centuries, classic “great man” accounts of contingencies, surprises, decisions, ironies and character, and the vivid experiences of those previously marginalized: women, African-Americans, Native Americans, homosexuals. It encompasses interesting takes on democracy and technology, shifts in demographics, revolutions in economics and the very nature of modernity. It’s a big sweeping book, a way for us to take stock at this point in the journey, to look back, to remind us who we are and to point to where we’re headed.

It isn’t until you start reading it that you realize how much we need a book like this one at this particular moment. “These Truths,” by Jill Lepore — a professor at Harvard and a staff writer at The New Yorker — is a one-volume history of the United States, constructed around a traditional narrative, that takes you from the 16th to the 21st century. It tries to take in almost everything, an impossible task, but I’d be hard-pressed to think she could have crammed more into these 932 highly readable pages. It covers the history of political thought, the fabric of American social life over the centuries, classic “great man” accounts of contingencies, surprises, decisions, ironies and character, and the vivid experiences of those previously marginalized: women, African-Americans, Native Americans, homosexuals. It encompasses interesting takes on democracy and technology, shifts in demographics, revolutions in economics and the very nature of modernity. It’s a big sweeping book, a way for us to take stock at this point in the journey, to look back, to remind us who we are and to point to where we’re headed.

This is not an account of relentless progress. It’s much subtler and darker than that. It reminds us of some simple facts so much in the foreground that we must revisit them: “Between 1500 and 1800, roughly two and a half million Europeans moved to the Americas; they carried 12 million Africans there by force; and as many as 50 million Native Americans died, chiefly of disease. … Taking possession of the Americas gave Europeans a surplus of land; it ended famine and led to four centuries of economic growth.” Nothing like this had ever happened in world history; and nothing like it is possible again. The land was instantly a refuge for religious dissenters, a new adventure in what we now understand as liberalism and a brutal exercise in slave labor and tyranny. It was a vast, exhilarating frontier and a giant, torturing gulag at the same time. Over the centuries, in Lepore’s insightful telling, it represented a giant leap in productivity for humankind: “Slavery was one kind of experiment, designed to save the cost of labor by turning human beings into machines. Another kind of experiment was the invention of machines powered by steam.” It was an experiment in the pursuit of happiness, but it was in effect the pursuit of previously unimaginable affluence.

More here.

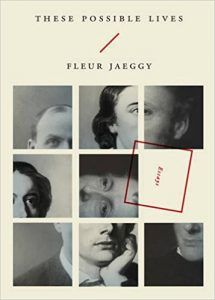

Consider Oliver Munday’s striking cover for These Possible Lives, one of the slim, sharp, dark works of Swiss/Italian author Fleur Jaeggy. The tile motif, bearing eight gray, equal segments from historical portraits of the book’s subjects, is immediately captivating; one glimpses mouths and eyes, poignant gazes into a mercurial unknown, or unsettling direct eye contact that seems to say, there are truths within this small book, but whose truth may they be? This obfuscation is furthered by Munday’s decision to create a ninth tile without image, choosing instead a tilted red box containing that imprecise, strange word, “Essays.” I pick up the book, read the title, These Possible Lives, and think to myself, what is possible about historically recorded lives. A simple red backslash wants to point me down, to the broken mosaic of possibility below, however, I realize red warns, and the indirect backslash conveys hesitation. This cover does a wonderful job trying to dissuade one from any clear preconceptions of the text within, while equally stoking my intense curiosity.

Consider Oliver Munday’s striking cover for These Possible Lives, one of the slim, sharp, dark works of Swiss/Italian author Fleur Jaeggy. The tile motif, bearing eight gray, equal segments from historical portraits of the book’s subjects, is immediately captivating; one glimpses mouths and eyes, poignant gazes into a mercurial unknown, or unsettling direct eye contact that seems to say, there are truths within this small book, but whose truth may they be? This obfuscation is furthered by Munday’s decision to create a ninth tile without image, choosing instead a tilted red box containing that imprecise, strange word, “Essays.” I pick up the book, read the title, These Possible Lives, and think to myself, what is possible about historically recorded lives. A simple red backslash wants to point me down, to the broken mosaic of possibility below, however, I realize red warns, and the indirect backslash conveys hesitation. This cover does a wonderful job trying to dissuade one from any clear preconceptions of the text within, while equally stoking my intense curiosity.

The manuscript for My Life With

The manuscript for My Life With  It isn’t until you start reading it that you realize how much we need a book like this one at this particular moment. “These Truths,” by

It isn’t until you start reading it that you realize how much we need a book like this one at this particular moment. “These Truths,” by  There are images on the walls of caves, whether we put them there or not. Or, more precisely, we create images on the walls of caves, whether with charcoal and manganese or simply with our imaginations. Michelangelo’s well-known claim that he simply released from stone what was already there is straightforwardly true of Paleolithic artists. They placed their lines where the contours already suggested animal motion.

There are images on the walls of caves, whether we put them there or not. Or, more precisely, we create images on the walls of caves, whether with charcoal and manganese or simply with our imaginations. Michelangelo’s well-known claim that he simply released from stone what was already there is straightforwardly true of Paleolithic artists. They placed their lines where the contours already suggested animal motion. In the 1940s, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department began trying to move bighorns back into their historic habitats. Those relocations continue today, and they’ve been increasingly successful at restoring the extirpated herds. But the lost animals aren’t just lost bodies. Their knowledge also died with them—and that is not easily replaced.

In the 1940s, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department began trying to move bighorns back into their historic habitats. Those relocations continue today, and they’ve been increasingly successful at restoring the extirpated herds. But the lost animals aren’t just lost bodies. Their knowledge also died with them—and that is not easily replaced. ‘If we don’t do this

‘If we don’t do this THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACEBOOK

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACEBOOK When the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle was asked whether he read novels, he famously replied, without missing a beat, “Oh, yes—all six, every year.” And without missing a beat we get the joke, of course, not because we believe that Jane Austen’s novels throw all others into the shadows (though we do), and not because they bear annual rereading (though they do), but rather because we all know—or think we know—that she wrote six of them.

When the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle was asked whether he read novels, he famously replied, without missing a beat, “Oh, yes—all six, every year.” And without missing a beat we get the joke, of course, not because we believe that Jane Austen’s novels throw all others into the shadows (though we do), and not because they bear annual rereading (though they do), but rather because we all know—or think we know—that she wrote six of them. A massive study of nearly 4,000 variants in a gene associated with cancer could help to pinpoint people at risk for breast or ovarian tumours. The information is sorely needed: millions of people have had their BRCA1 gene sequenced. Some variations in the DNA sequence of BRCA1are linked to breast and ovarian cancer; others are thought to be safe. But

A massive study of nearly 4,000 variants in a gene associated with cancer could help to pinpoint people at risk for breast or ovarian tumours. The information is sorely needed: millions of people have had their BRCA1 gene sequenced. Some variations in the DNA sequence of BRCA1are linked to breast and ovarian cancer; others are thought to be safe. But

Film and theatre are not the only cultural sectors to have come into Fidesz’s crosshairs – the offensive was indeed ‘total’. For example, shortly after Orbán assumed power, the National Cultural Fund was restructured. Originally an independent body, it was responsible for distributing subsidies across all cultural sectors. A great advantage of the cultural fund was that it was independent of government. But Orbán subordinated it to a minister and a secretary of state, who henceforth had the power to revise the decisions of the committees responsible for the various cultural sectors. In summer 2010, members of the Cultural Fund’s councils responsible for publishing were replaced with Fidesz sympathizers. The procedure appeared paradoxical. The state created a fund which was charged not only with distributing money, but also with ensuring that decisions be made by qualified representatives. However, the government then intervened to ensure that these qualified, elected experts could not make democratic decisions about the money.

Film and theatre are not the only cultural sectors to have come into Fidesz’s crosshairs – the offensive was indeed ‘total’. For example, shortly after Orbán assumed power, the National Cultural Fund was restructured. Originally an independent body, it was responsible for distributing subsidies across all cultural sectors. A great advantage of the cultural fund was that it was independent of government. But Orbán subordinated it to a minister and a secretary of state, who henceforth had the power to revise the decisions of the committees responsible for the various cultural sectors. In summer 2010, members of the Cultural Fund’s councils responsible for publishing were replaced with Fidesz sympathizers. The procedure appeared paradoxical. The state created a fund which was charged not only with distributing money, but also with ensuring that decisions be made by qualified representatives. However, the government then intervened to ensure that these qualified, elected experts could not make democratic decisions about the money. The Bureau had received credible evidence regarding Sontag’s trip to Hanoi—a feature in Esquire describing her experiences talking to leading figures of the North Vietnamese government, including Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, that would later be adapted into the book Trip to Hanoi.

The Bureau had received credible evidence regarding Sontag’s trip to Hanoi—a feature in Esquire describing her experiences talking to leading figures of the North Vietnamese government, including Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, that would later be adapted into the book Trip to Hanoi. It would be uncool, priggish, unthinking to care too much about the artist’s intoxication. Torments require relief and expression: numbing and utterance; alcohol and art. You can’t unpick the work from the circumstances of its creation, nor should you want to. In 1975, the critic Lewis Hyde tried caring about Berryman. A few years after the poet’s death, Hyde published an essay, an angry blast against the romanticization of the inebriated artist. When Hyde read The Dream Songs he didn’t hear the genius so much as “the booze talking”. “Its tone is a moan that doesn’t revolve.” Hyde seemed to believe – unfashionably – that Berryman’s work would have been better had he been sober.

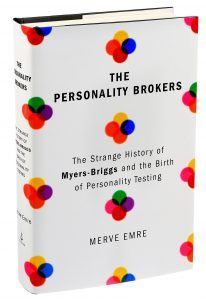

It would be uncool, priggish, unthinking to care too much about the artist’s intoxication. Torments require relief and expression: numbing and utterance; alcohol and art. You can’t unpick the work from the circumstances of its creation, nor should you want to. In 1975, the critic Lewis Hyde tried caring about Berryman. A few years after the poet’s death, Hyde published an essay, an angry blast against the romanticization of the inebriated artist. When Hyde read The Dream Songs he didn’t hear the genius so much as “the booze talking”. “Its tone is a moan that doesn’t revolve.” Hyde seemed to believe – unfashionably – that Berryman’s work would have been better had he been sober. Merve Emre’s new book begins like a true-crime thriller, with the tantalizing suggestion that a number of unsettling revelations are in store. Early in “The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing,” she recalls the “low-level paranoia” she started to feel as she researched her subject: “Files disappear. Tapes are erased. People begin to watch you.” Archival gatekeepers were by turns controlling and evasive, acting like furtive trustees of terrible secrets. What, she wanted to know, were they trying to hide?

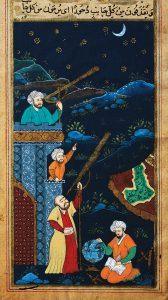

Merve Emre’s new book begins like a true-crime thriller, with the tantalizing suggestion that a number of unsettling revelations are in store. Early in “The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing,” she recalls the “low-level paranoia” she started to feel as she researched her subject: “Files disappear. Tapes are erased. People begin to watch you.” Archival gatekeepers were by turns controlling and evasive, acting like furtive trustees of terrible secrets. What, she wanted to know, were they trying to hide? As I prepared to teach my class ‘Science and Islam’ last spring, I noticed something peculiar about the book I was about to assign to my students. It wasn’t the text – a wonderful translation of a medieval Arabic encyclopaedia – but the cover. Its illustration showed scholars in turbans and medieval Middle Eastern dress, examining the starry sky through telescopes. The miniature purported to be from the premodern Middle East, but something was off.

As I prepared to teach my class ‘Science and Islam’ last spring, I noticed something peculiar about the book I was about to assign to my students. It wasn’t the text – a wonderful translation of a medieval Arabic encyclopaedia – but the cover. Its illustration showed scholars in turbans and medieval Middle Eastern dress, examining the starry sky through telescopes. The miniature purported to be from the premodern Middle East, but something was off. So effectively has the Beltway establishment captured the concept of national security that, for most of us, it automatically conjures up images of terrorist groups, cyber warriors, or “rogue states.” To ward off such foes, the United States maintains a historically unprecedented

So effectively has the Beltway establishment captured the concept of national security that, for most of us, it automatically conjures up images of terrorist groups, cyber warriors, or “rogue states.” To ward off such foes, the United States maintains a historically unprecedented