by Timothy Don

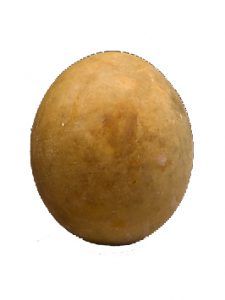

Speak the word “discovery” and familiar images of explorers, scientists, ships, and treasure chests come to mind. To look into the visual record of “discovery” over the past 50,000 years, however, is to witness the concept expand, swell, and overwhelm the imagination. There is a wonder that arises in the wake of one’s research with the realization that the deeper and closer one looks, the wider, richer, and more capacious the topic at hand becomes. Consider the egg.

A simple egg. The familiarity of its shape is unnerving, even disarming. Hovering there, alone in space, it has the weight of a moon or a planet. A red planet. A symbol of discovery in its expansive, exploratory sense: to discover is to reach out into space, to land on the moon, to plan for Mars. But…this object is not Mars. It is an egg. It is an ostrich egg, more than 5,000 years old, from the predynastic period of Northern Upper Egypt, dug out of a tomb. Mars remains undiscovered. This is an artifact from an era now lost to us, uncovered by a forgotten Egyptologist from the 19th century. It belongs to the past. This is an actual discovery. And it is wonderful. It is pure potential. It has been discovered, but it remains uncracked. Full of mystery, this old egg from the past, it fills you with wonder. At that moment a gestalt switch gets thrown, and one realizes that discovery’s arrow points not only forward and outward to unexplored planets, but backward and inward to things lost, buried, and forgotten. To discover a thing is also to discover the past, and the act of discovery is about the recovery of the past just as much as it is about the probing of the future. And so a planet (symbol of the undiscovered future) becomes an artifact (material expression of the discovered past), and the artifact (the egg) becomes a mystery, a wonder, a promise. To be an egg is to promise discovery. Every egg, from this one (c. 3400bc) to the one you opened into a frying pan this morning, contains and shelters something utterly familiar and utterly unique, something waiting for you to find it. Every egg is a discovery.

There are certain artists who seem to have something to say about everything and whose work as a result appears regularly in the pages of the journal at which I serve as visual curator. Hieronymus Bosch is one. Caravaggio is another. Paul Klee and William Kentridge make the list. The genius of these artists (and many others) makes their work ever-contemporary, as immediate and compelling today as it was when they made it. The density of their work allows it to absorb the assault of time, so that its meaning can shift and apply itself to any period without diluting the purity of its original conception and execution. Read more »

Little Miracles 2:

Little Miracles 2:

The dangers of climate change pose a threat to all of humankind and to ecosystems all over the world. Does this mean that all humans need to equally shoulder the responsibility to mitigate climate change and its effects? The concept of CBDR (common but differentiated responsibilities) is routinely discussed at international negotiations about climate change mitigation. The basic principle of CBDR in the context of climate change is that highly developed countries have historically contributed far more than to climate change and therefore need to reduce their carbon footprint far more than less developed countries. The per capita rate of vehicles in the United States is approximately 90 cars per 100 people, whereas the rate in India is 5 cars per 100 people. The total per capita carbon footprint includes a plethora of factors such as carbon emissions derived from industry, air travel and electricity consumption of individual households. As of 2015, the

The dangers of climate change pose a threat to all of humankind and to ecosystems all over the world. Does this mean that all humans need to equally shoulder the responsibility to mitigate climate change and its effects? The concept of CBDR (common but differentiated responsibilities) is routinely discussed at international negotiations about climate change mitigation. The basic principle of CBDR in the context of climate change is that highly developed countries have historically contributed far more than to climate change and therefore need to reduce their carbon footprint far more than less developed countries. The per capita rate of vehicles in the United States is approximately 90 cars per 100 people, whereas the rate in India is 5 cars per 100 people. The total per capita carbon footprint includes a plethora of factors such as carbon emissions derived from industry, air travel and electricity consumption of individual households. As of 2015, the

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel

It must be hard for

It must be hard for  In 1961, Piero Manzoni created his most famous art work—ninety small, sealed tins, titled “Artist’s Shit.” Its creation was said to be prompted by Manzoni’s father, who owned a canning factory, telling his son, “Your work is shit.” Manzoni intended “Artist’s Shit” in part as a commentary on consumerism and the obsession we have with artists. As Manzoni put it, “If collectors really want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit.”

In 1961, Piero Manzoni created his most famous art work—ninety small, sealed tins, titled “Artist’s Shit.” Its creation was said to be prompted by Manzoni’s father, who owned a canning factory, telling his son, “Your work is shit.” Manzoni intended “Artist’s Shit” in part as a commentary on consumerism and the obsession we have with artists. As Manzoni put it, “If collectors really want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit.” As the EU struggles to rein in some member states that are backsliding on democratic standards, a critical vote in the European Parliament next week could be a decisive moment.

As the EU struggles to rein in some member states that are backsliding on democratic standards, a critical vote in the European Parliament next week could be a decisive moment. On a late Friday afternoon in November last year,

On a late Friday afternoon in November last year,  In a

In a  It could all go wrong in an instant. In Yasmina Reza’s unsettling new novel, Elisabeth, the narrator, looks back on an evening in a Paris suburb that began in the most ordinary way — a casual evening party for family, friends and neighbors — and ended in catastrophe. The nature of the disaster unfolds across a brisk 200 pages, but it is foreshadowed from the very beginning, when Elisabeth observes her neighbor, Jean-Lino, rigid in an uncomfortable chair, surrounded by the detritus of the festivities, “all the leavings of the party arranged in an optimistic moment. Who can determine the starting point of events?”

It could all go wrong in an instant. In Yasmina Reza’s unsettling new novel, Elisabeth, the narrator, looks back on an evening in a Paris suburb that began in the most ordinary way — a casual evening party for family, friends and neighbors — and ended in catastrophe. The nature of the disaster unfolds across a brisk 200 pages, but it is foreshadowed from the very beginning, when Elisabeth observes her neighbor, Jean-Lino, rigid in an uncomfortable chair, surrounded by the detritus of the festivities, “all the leavings of the party arranged in an optimistic moment. Who can determine the starting point of events?”