Month: September 2018

George Walker (1922 – 2018)

How to Play Our Way to a Better Democracy

Haidt and Lukianoff in The New York Times:

Before he died, Senator John McCain wrote a loving farewell statement to his fellow citizens of “the world’s greatest republic, a nation of ideals, not blood and soil.” Senator McCain also described our democracy as “325 million opinionated, vociferous individuals.” How can that many individuals bind themselves together to create a great nation? What special skills do we need to develop to compensate for our lack of shared ancestry? When Alexis de Tocqueville toured America in 1831, he concluded that one secret of our success was our ability to solve problems collectively and cooperatively. He praised our mastery of the “art of association,” which was crucial, he believed, for a self-governing people.

Before he died, Senator John McCain wrote a loving farewell statement to his fellow citizens of “the world’s greatest republic, a nation of ideals, not blood and soil.” Senator McCain also described our democracy as “325 million opinionated, vociferous individuals.” How can that many individuals bind themselves together to create a great nation? What special skills do we need to develop to compensate for our lack of shared ancestry? When Alexis de Tocqueville toured America in 1831, he concluded that one secret of our success was our ability to solve problems collectively and cooperatively. He praised our mastery of the “art of association,” which was crucial, he believed, for a self-governing people.

In recent years, however, we have become less artful, particularly about crossing party lines. It’s not just Congress that has lost the ability to cooperate. As partisan hostility has increased, Americans report feeling fear and loathing toward people on the other side and have become increasingly less willing to date or marry someone of a different party. Some restaurants won’t serve customers who work for — or even just support — the other team or its policies. Support for democracy itself is in decline. What can we do to reverse these trends? Is there some way to teach today’s children the art of association, even when today’s adults are poor models? There is. It’s free, it’s fun and it confers so many benefits that theAmerican Academy of Pediatrics recently urged Americans to give far more of it to their children. It’s called play — and it matters not only for the health of our children but also for the health of our democracy.

More here.

The First Day’s Interview

Norman Mailer in The Paris Review (1961):

Sometimes I think my work may be seen eventually as some literary equivalent (obviously much reduced in scale) to Picasso. My vice, my strength, is beginnings. Usually I begin well—it is just that I seem to have little interest in finishing. It seems adequate to start a piece, go far enough to glimpse what the possibilities and limitations might be, and then move on. Which for that matter is close to the discrete temper of our time.

Sometimes I think my work may be seen eventually as some literary equivalent (obviously much reduced in scale) to Picasso. My vice, my strength, is beginnings. Usually I begin well—it is just that I seem to have little interest in finishing. It seems adequate to start a piece, go far enough to glimpse what the possibilities and limitations might be, and then move on. Which for that matter is close to the discrete temper of our time.

This interview was an experiment. Unfinished one obviously. As an attempt to breach an opening into The Psychology of the Orgy, it has a few charms. It may even be possible to write a good book this way; such a book would be a novel. I can think of nothing very much like it, except perhaps for Gide’s Corydon, but the difference is most particular. In Corydon, Gide stepped aside from his Self, and appeared nominally as André Gide-the-Interviewer speaking to some young talented homosexual artist, a man not unlike the hero of The Immoralist. He thus divided his dialogue between two Gides: a young, conventional, severe, most well-mannered and rather agitated young prig, (the ”I” of Corydon) and the subject, a saturnine, scientifically articulated, rather sinister (in the proper tone of the period) man of talent.

In this fragment—The First Day’s Interview—the encounter is less narcissistic. The subject is a Norman Mailer, a weary, cynical, now philosophically turned hipster of middle years; the interviewer is a young man of a sort the author was never very close to. The vector of the dialogue is therefore opposite to Corydon. In that book, Gide appears in a conventional suit and tries to take a trip across the room into himself. He is hoping to seduce his readers. On the contrary, in this piece printed here, the author in full panoply is pretending to travel back to society in order to seduce the brain of the young critic he never was. One might call it a Counter-Diabolism to Gide’s method, and be not at all presumptuous—if one managed, small matter, to finish the book.

More here.

Prince – Jazz Funk Sessions 1977 (Instrumental)

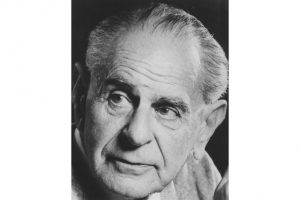

The Paradox of Karl Popper

John Horgan in Scientific American:

John Horgan in Scientific American:

I began to discern the paradox lurking at the heart of Karl Popper’s career when, prior to interviewing him in 1992, I asked other philosophers about him. Queries of this kind usually elicit dull, generic praise, but not in Popper’s case. Everyone said this opponent of dogmatism was almost pathologically dogmatic. There was an old joke about Popper: The Open Society and its Enemies should have been titled The Open Society by One of its Enemies.

To arrange an interview, I telephoned the London School of Economics, where Popper had taught since the late 1940s. A secretary said he generally worked at his home in a London suburb. When I called, a woman with an imperious, German-accented voice answered. Mrs. Mew, housekeeper and assistant to “Sir Karl.” Before he would see me, I had to send her a sample of my writings. She gave me a list of a dozen or so books by Sir Karl that I should read before the meeting. After numerous faxes and calls, she set a date. When I asked for directions from a nearby train station, Mrs. Mew assured me that all the cab drivers knew where Sir Karl lived. “He’s quite famous.”

More here.

Silicon Valley and the Quest for a Utopian Workplace

Chris Mackin in TNR:

Chris Mackin in TNR:

…developments at Google and Tesla signal a new reckoning by employees—white collar and blue collar—with the limitations of the modern utopian workplace. They describe pent-up forces, now apparently loosened, that will not be tamed by vague managerial assurances, or yogurt stands. Facebook, Amazon, and Apple may not be far behind.

The problems highlighted are structural and longstanding. They point to a fundamental flaw with a particular and peculiar institution, the employment relationship, which is so ubiquitous that it appears natural. A fundamental fact haunts that relationship across all kinds of workplaces, modern and traditional. Employees without substantial ownership and governance rights, employees who are not members of democratic corporations, have no standing. They are merely rented humans. They are visitors on someone else’s planet.

Union representation can mitigate these problems. It can circumscribe the terms of that rental arrangement, but it cannot cure it. It is not likely that stability or real progress will be found at these workplaces without something more comprehensive—without a genuine workplace democracy that turns employees into part-owners of the companies where they work.

More here.

The Limits of Reason

Philip Pullman at The Guardian:

But rationalism doesn’t make the magical universe go away. Possibly because I earn my living as a writer of fiction, and possibly because it’s just the sensible thing to do, I like to pay attention to everything I come across, including things that evoke the uncanny or the mysterious. Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto (I am human, I consider nothing human alien to me). My attitude to magical things is very much like that attributed to the great physicist Niels Bohr. Asked about the horseshoe that used to hang over the door to his laboratory, he’s claimed to have said that he didn’t believe it worked but he’d been told that it worked whether he believed in it or not. When it comes to belief in lucky charms, or rings engraved with the names of angels, or talismans with magic squares, it’s impossible to defend it and absurd to attack it on rational grounds because it’s not the kind of material on which reason operates. Reason is the wrong tool. Trying to understand superstition rationally is like trying to pick up something made of wood by using a magnet.

But rationalism doesn’t make the magical universe go away. Possibly because I earn my living as a writer of fiction, and possibly because it’s just the sensible thing to do, I like to pay attention to everything I come across, including things that evoke the uncanny or the mysterious. Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto (I am human, I consider nothing human alien to me). My attitude to magical things is very much like that attributed to the great physicist Niels Bohr. Asked about the horseshoe that used to hang over the door to his laboratory, he’s claimed to have said that he didn’t believe it worked but he’d been told that it worked whether he believed in it or not. When it comes to belief in lucky charms, or rings engraved with the names of angels, or talismans with magic squares, it’s impossible to defend it and absurd to attack it on rational grounds because it’s not the kind of material on which reason operates. Reason is the wrong tool. Trying to understand superstition rationally is like trying to pick up something made of wood by using a magnet.

more here.

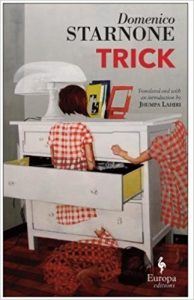

‘Trick’ by Domenico Starnone

Elizabeth de Cleyre at The Quarterly Conversation:

Perhaps it is Starnone’s newness in the English-speaking world that explains why reviewers have tended to jump over his proven track record and speculate about his connections to the mysterious and pseudonymous Italian author Elena Ferrante. Their rumored personal relationship is beside the point, but their books are similarly staggering—and the resemblances between their styles and subjects is hard to ignore.

Perhaps it is Starnone’s newness in the English-speaking world that explains why reviewers have tended to jump over his proven track record and speculate about his connections to the mysterious and pseudonymous Italian author Elena Ferrante. Their rumored personal relationship is beside the point, but their books are similarly staggering—and the resemblances between their styles and subjects is hard to ignore.

Set in modern-day Naples, Trick follows seventy-something illustrator Daniele Mallarico as he decamps to the house where he grew up. There, he cares for his grandson Mario while the boy’s parents are at a conference. Only four years old, Mario possesses an uncanny breadth of vocabulary, and an unsettling grasp of how the world functions.

more here.

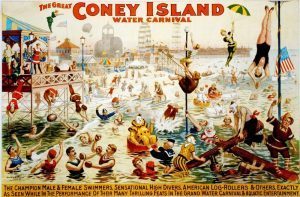

Coney Island: The Aristocracy of Freakdom

ee cummings at The Paris Review:

The incredible temple of pity and terror, mirth and amazement, which is popularly known as Coney Island, really constitutes a perfectly unprecedented fusion of the circus and the theatre. It resembles the theatre, in that it fosters every known species of illusion. It suggests the circus, in that it puts us in touch with whatever is hair-raising, breath-taking and pore-opening. But Coney has a distinct drop on both theatre and circus. Whereas at the theatre we merely are deceived, at Coney we deceive ourselves. Whereas at the circus we are merely spectators of the impossible, at Coney we ourselves perform impossible feats—we turn all the heavenly somersaults imaginable and dare all the delirious dangers conceivable; and when, rushing at horrid velocity over irrevocable precipices, we beard the force of gravity in his lair, no acrobat, no lion tamer, can compete with us.

The incredible temple of pity and terror, mirth and amazement, which is popularly known as Coney Island, really constitutes a perfectly unprecedented fusion of the circus and the theatre. It resembles the theatre, in that it fosters every known species of illusion. It suggests the circus, in that it puts us in touch with whatever is hair-raising, breath-taking and pore-opening. But Coney has a distinct drop on both theatre and circus. Whereas at the theatre we merely are deceived, at Coney we deceive ourselves. Whereas at the circus we are merely spectators of the impossible, at Coney we ourselves perform impossible feats—we turn all the heavenly somersaults imaginable and dare all the delirious dangers conceivable; and when, rushing at horrid velocity over irrevocable precipices, we beard the force of gravity in his lair, no acrobat, no lion tamer, can compete with us.

more here.

A Grisly Fable of Ottoman Albania

Jason Goodwin in the New York Times:

After World War II, tiny Albania became a hermit state, rigidly controlled by a Stalinist dictator, Enver Hoxha, who broke with both the Soviet Union and Maoist China, desecrated the country’s mosques and churches and planted the beaches across from the Greek island of Corfu with pillboxes before his regime collapsed in 1990, five years after his death. But the Albanian writer Ismail Kadare’s 1978 novel, “The Traitor’s Niche,” is an allegorical fable, finally (and very elegantly) translated into English by John Hodgson, about an earlier Albania, which for centuries formed part of the sprawling Ottoman Empire.

After World War II, tiny Albania became a hermit state, rigidly controlled by a Stalinist dictator, Enver Hoxha, who broke with both the Soviet Union and Maoist China, desecrated the country’s mosques and churches and planted the beaches across from the Greek island of Corfu with pillboxes before his regime collapsed in 1990, five years after his death. But the Albanian writer Ismail Kadare’s 1978 novel, “The Traitor’s Niche,” is an allegorical fable, finally (and very elegantly) translated into English by John Hodgson, about an earlier Albania, which for centuries formed part of the sprawling Ottoman Empire.

The novel begins with a severed head sitting in a dish of honey. It occupies a special niche in a square of the imperial capital, Istanbul, where it outstares the milling crowds. The head belonged to a hapless pasha who failed to suppress a rebellion in the distant province of Albania; it is tended by Abdulla, the guardian of the heads, and regularly inspected for signs of decay by a benign doctor who also advises Abdulla on how to overcome his impotence.

More here.

Can we choose our own identity?

Kwame Anthony Appiah in The Guardian:

In April 2015, after a long and very public career, first as a male decathlete, then as a reality TV star, Caitlyn Jenner announced to the world she was a trans woman. Asked about her sexuality, Jenner explained that she had always been heterosexual, and indeed she had fathered six children in three marriages. She understood, though, that many people were confused about the distinction between sexual orientation and gender identity, and so she said: “Let’s go with ‘asexual’ for now.”

In April 2015, after a long and very public career, first as a male decathlete, then as a reality TV star, Caitlyn Jenner announced to the world she was a trans woman. Asked about her sexuality, Jenner explained that she had always been heterosexual, and indeed she had fathered six children in three marriages. She understood, though, that many people were confused about the distinction between sexual orientation and gender identity, and so she said: “Let’s go with ‘asexual’ for now.”

Isn’t it up to her? What could be more personal than the question of who she is – what she is? Isn’t your identity, as people often say, “your truth”? The question is straightforward; the answer is anything but. And that’s because a seismic fault line runs through contemporary talk of identity, regularly issuing tremors and quakes. Your identity is meant to be the truth of who you are. But what’s the truth about identity? An identity, at its simplest, is a label we apply to ourselves and to others. Your gender. Your sexuality. Your class, nationality, ethnicity, region, religion, to start a list of categories. (Raise your hand if you are a straight, male, working-class, Afro-Latinx evangelical US southerner.) Labels always come with rules of ascription. When we apply a label to ourselves, we’re accepting that we have some qualifying trait – say, Latin or African ancestry, male or female sex organs, attractions to one gender or another, the right to a German passport.

More here.

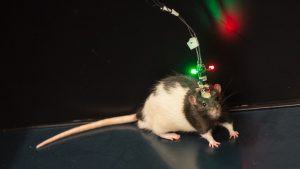

Scientists found brain’s internal clock that influences how we perceive time

Jennifer Ouellette in Ars Technica:

How the brain fixes the timing of the events we experience depends on episodic memory. Whenever you remember key events from your past, you are tapping into episodic memory, which encodes what happened, where it happened, and when it happened, doing so for all our remembered experiences. Neuroscientists know the brain must have a kind of internal clock or pacemaker to help it track those experiences and record them as memories.

How the brain fixes the timing of the events we experience depends on episodic memory. Whenever you remember key events from your past, you are tapping into episodic memory, which encodes what happened, where it happened, and when it happened, doing so for all our remembered experiences. Neuroscientists know the brain must have a kind of internal clock or pacemaker to help it track those experiences and record them as memories.

In a new paper in Nature, researchers at the Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience (KISN) in Norway report that they have pinpointed a collection of interconnected brain cells that provides this clock. And it just happens to be located right next to the brain region that keeps track of where we are in space.

Scientists have known how the brain encodes the aspect of space in our memories since 2005, with the Nobel Prize-winning discovery of grid cells. These reside in a brain region called the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC), and they collectively map our environment into hexagonal units.

More here.

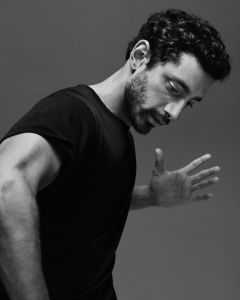

Riz Ahmed Acts His Way Out of Every Cultural Pigeonhole

Carvell Wallace in The New York Times:

When I let it slip that the press kit I’d been given had referred to him as a ‘Renaissance man,’ Riz Ahmed looked angrily down into his breakfast, a chicken-quinoa bowl with extra chicken. It lasted for just a moment, but the image stayed with me, because it was the only time during our approximately 10 hours together — breakfast in Brooklyn, private sessions with the Islamic art collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, YouTube sessions listening to 1970s Qawwali-inspired Iraqi disco, talks on park benches in Fort Greene, tea on the sidewalk of Fulton Avenue and even dinner in Boston, where Ahmed was filming an independent feature about a heavy-metal drummer who’s losing his hearing — that the 35-year-old actor seemed to be truly, genuinely upset.

When I let it slip that the press kit I’d been given had referred to him as a ‘Renaissance man,’ Riz Ahmed looked angrily down into his breakfast, a chicken-quinoa bowl with extra chicken. It lasted for just a moment, but the image stayed with me, because it was the only time during our approximately 10 hours together — breakfast in Brooklyn, private sessions with the Islamic art collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, YouTube sessions listening to 1970s Qawwali-inspired Iraqi disco, talks on park benches in Fort Greene, tea on the sidewalk of Fulton Avenue and even dinner in Boston, where Ahmed was filming an independent feature about a heavy-metal drummer who’s losing his hearing — that the 35-year-old actor seemed to be truly, genuinely upset.

It’s not that he doesn’t get animated. He does. Talking with Ahmed can be a little like sparring, a little like co-writing a constitution, a little like saving the world in an 11th-hour meeting. He interrupts, then apologizes for interrupting, then interrupts again. He can deliver entirely publishable essays off the top of his head. He pounds the table when talking about global injustices, goes back to edit his sentences minutes after they were spoken, challenges the premises of your sentences before you’re halfway through speaking. This is what happens when you cut your teeth on both prep-school debate teams and late-night freestyle rap battles, as Ahmed has. He is like someone who wants to speak truth to power but now ispower — famous enough, at least, to have people listen to his ideas. He is like someone very smart who also cares a lot. He is like someone who doesn’t want to be misunderstood.

More here.

Blast from the past: Meta-Free-Phor-All

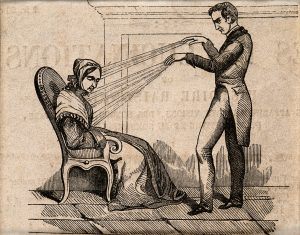

He Blinded Me with Science

Emily Ogden in Lapham’s Quarterly:

In 1784, America’s soon-to-be second, third, and fourth presidents celebrated the publication of a report debunking the practices of Franz Anton Mesmer, a Vienna-educated physician whose name gives us the word mesmerizing. John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madisonall rejoiced to know that Mesmer would no longer impose on credulous Parisians with his invisible fluid of animal magnetism, a living or vital counterpart of mineral magnetism. Mesmer said that animal magnetism crackled all around us, though it was especially concentrated in human nerves. He claimed he could cure illnesses by manipulating this invisible fluid in the ailing body. His theory did not seem as implausible in 1784 as it does now; it crossed ancient humoral medicine with the best accounts then available of how electricity and magnetism worked. Mesmer had made a few false starts in Austria, including the time he promoted a theory of “animal gravitation,” before taking Paris by storm in 1778. While he called his practice animal magnetism, his opponents would coin, and his successors would eventually adopt, the term mesmerism.

In 1784, America’s soon-to-be second, third, and fourth presidents celebrated the publication of a report debunking the practices of Franz Anton Mesmer, a Vienna-educated physician whose name gives us the word mesmerizing. John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madisonall rejoiced to know that Mesmer would no longer impose on credulous Parisians with his invisible fluid of animal magnetism, a living or vital counterpart of mineral magnetism. Mesmer said that animal magnetism crackled all around us, though it was especially concentrated in human nerves. He claimed he could cure illnesses by manipulating this invisible fluid in the ailing body. His theory did not seem as implausible in 1784 as it does now; it crossed ancient humoral medicine with the best accounts then available of how electricity and magnetism worked. Mesmer had made a few false starts in Austria, including the time he promoted a theory of “animal gravitation,” before taking Paris by storm in 1778. While he called his practice animal magnetism, his opponents would coin, and his successors would eventually adopt, the term mesmerism.

Mesmer’s patients—most of them female and well-to-do—found him through word-of-mouth and in pamphlets advertising his metaphysical talents. They met in his richly appointed treatment salon, where they gathered around a bucket filled with shards of glass and water that concentrated the life-giving animal-magnetic fluid. Mesmer said all illnesses had the same cause: a blockage in the flow of animal magnetism.

More here.

Saturday Poem

The Problem of Describing Trees

The aspen glitters in the wind

And that delights us.

The leaf flutters, turning,

Because that motion in the heat of August

Protects its cells from drying out. Likewise the leaf

Of the cottonwood.

The gene pool threw up a wobbly stem

And the tree danced. No.

The tree capitalized.

No. There are limits to saying,

In language, what the tree did.

It is good sometimes for poetry to disenchant us.

Dance with me, dancer. Oh, I will.

Mountains, sky,

The aspen doing something in the wind.

.

by Robert Hass

from Time and Materials

publisher: Ecco, 2007