by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

1. Roses

1. Roses

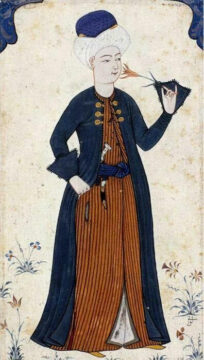

Miniatures and illuminated manuscripts from the Islamic world offer up an abundance of floral depictions. Cultivating gardens and replicating them in art, has a spiritual dimension, as gardens symbolize paradise; “Jannah” in the Qur’an is a “hidden garden” that inspires to be revealed and realized in the creative arts. Gardens have a place in the realm of earthly power too; from Spain to India, some of the most elaborate garden designs were commissioned under Muslim rule. In portraits of princes and noblemen, there is often a sprig of flowers or a single rose in one hand, slightly raised, whereas the body is angled to show the regalia: jewels, sashes and belts with daggers or swords. While a flower in bloom in an imperial image may symbolize vitality, refinement, and a concern for balancing the fierce with the tender, the true poignancy it evokes lies in its vulnerability and inevitable decline.

A famed ghazal verse captures a most spectacular swing of empire’s pendulum: the end of one of the wealthiest and culturally most opulent empires in history, the Mughal empire, whose dominion over large swathes of territory in South Asia was wrested from it by the British Raj. As he lies dying in exile (1862), the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar writes:

How hapless is Zafar, for his burial

Not even two yards of land could be found in the beloved’s neighborhood

Some of his most finely wrought poems are in the Sufi vein, exquisite verses that stand apart in the Urdu cannon. I would if I could, bring roses as homage to his resting place, left unmarked, in Burma where he died.

While the king yearns for two yards of burial ground in the land his ancestors ruled over with such pomp for centuries, the British Empire, though destined to be short-lived, is fast expanding, and by the nineteenth century, comprises nearly one-quarter of the world’s land surface. Read more »

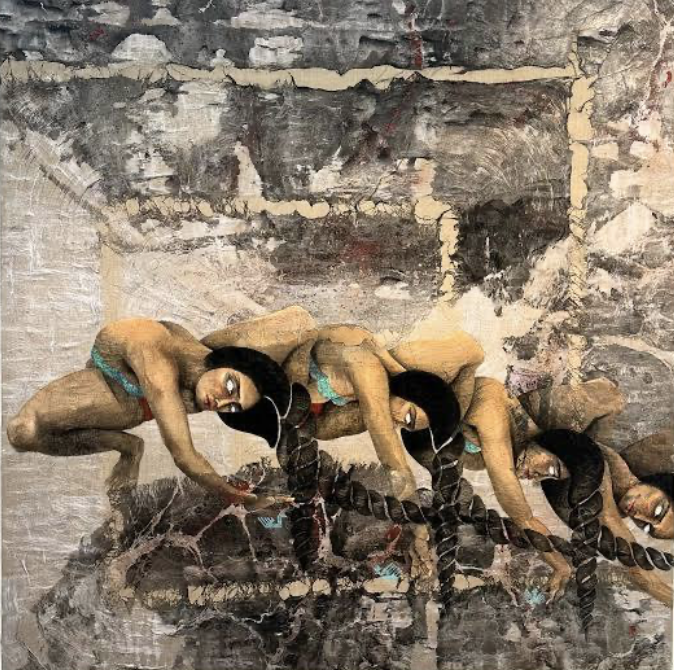

Hayv Kahraman. Rain Birds Ritual, 2025.

Hayv Kahraman. Rain Birds Ritual, 2025. Morgan Meis and I have been talking about art for years. We’re friends and interlocutors, so I’ll refer to him by first name here for the sake of transparency. Morgan writes about painting; I write about movies. We spent the pandemic exchanging letters with each other about films by Terrence Malick, Lars von Trier, and Krzysztof Kieślowski. These letters were later collected in a mad book called

Morgan Meis and I have been talking about art for years. We’re friends and interlocutors, so I’ll refer to him by first name here for the sake of transparency. Morgan writes about painting; I write about movies. We spent the pandemic exchanging letters with each other about films by Terrence Malick, Lars von Trier, and Krzysztof Kieślowski. These letters were later collected in a mad book called

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.

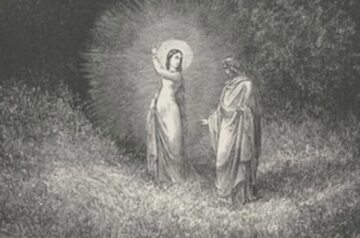

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing.

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing.