by Mindy Clegg

I think about this Le Guin quote often, especially in the current political climate. Far too many of us have embraced a kind of learned helplessness in the face of what are undoubtedly some of the most difficult and thorny of issues to face our species in our history. These overwhelming problems—climate change, systemic gun violence, exploitation of labor and resources, the rise of authoritarianism, and so on—are all byproducts of the modern neoliberal capitalist system. The current globalized socio-political-economic system seems so entrenched and solutions feel so impossible that many of us have given up trying to solve them via government regulation. Instead many of us embrace a cynical nihilism. We shrug our shoulders and accept that this is the only possible world, maybe pushing back against the worst edges of these problems, focusing on symptoms rather than the disease. Le Guin’s quote from a speech at an award ceremony offers us a different direction—that change can emerge out of the world of popular, mass produced culture. In recent years, our media seems more divided since the rise of cable TV and then social media. But the increasingly centralized corporate control of mass media has limited alternative voices and increased divisions among us. Many feel that there is no way to create a counterweight, given corporate capture of government regulation. Since the 1970s, many of us no longer see government regulation as a workable solution to dealing with various social problems. But given how many of these problems are a byproduct of unfettered capitalism, a strong, robust regulatory state designed to enhance the rights of the public can help solve these problems. But in order to ensure that does not become tyrannical itself, we also need strong independent, non-commercial cultural production to ensure the voices of the marginalized are heard. What does this look like and has it happened before? Absolutely. Let’s see some of this history to understand what is possible. Read more »

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

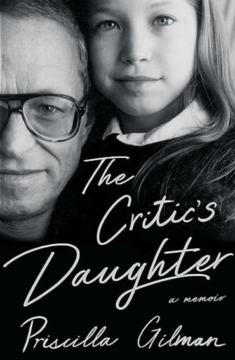

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

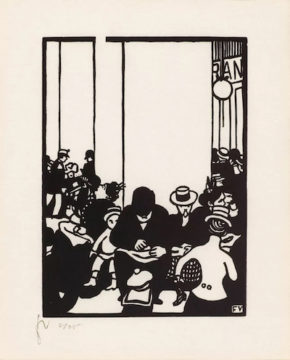

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

In the decade before World War I, the newspaper dominated life like it never would again. The radio was not yet fit for mass use, and neither was film or recording. It was then common for major cities to have a dozen or so morning papers competing for attention. Deceit, exaggeration, and gimmicks were typical, even expected, to boost readership. Rarely were reporters held to account.

You don’t have to fuck me. Or give me any money. You don’t have to shave your head or adopt a peculiar diet or wear an ugly smock or come live in my compound among fellow cult members. You don’t even have to believe in anything.

You don’t have to fuck me. Or give me any money. You don’t have to shave your head or adopt a peculiar diet or wear an ugly smock or come live in my compound among fellow cult members. You don’t even have to believe in anything.