by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

I walked through woods muddy and wet, feet sinking down into the boggy earth. With each step, mosquitoes rose up in clouds. It felt more like I was forging a river than walking a path through woods.

I was told that it was less than two miles to Robert Frost’s writing cabin in the woods. According to the Bread Crumb, the daily newsletter put out by the Bread Loaf Writers Conference, it was a must-see. Just follow the pink ribbons…it instructed. And sure enough, pretty pink ribbons were tied to tree branches, marking the way, whenever two roads diverged through the woods.

I had only applied to the conference on a whim. Well, not a whim exactly, but more like a major disappointment and a bad experience with a literary agent sent me spiraling… but then after a week of tears, I decided to just get back up again. What else could I do anyway? “Fall down seven times, get back up eight” 七転び八起き says the old Japanese proverb.

And so, I applied to several workshops and one residency.

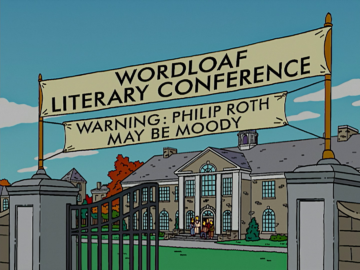

I don’t recall where or how I first heard about Bread Loaf. Maybe it was from that old Simpson’s episode, when Lisa launches tavern-owner Moe’s literary career by sending his poem to a magazine:

Howling at a concrete moon,

My soul smells like a dead pigeon after three weeks.

I shut my window and go to sleep.

In my dream I eat corn with my eyes.

Moe’s poem creates a literary splash, and he is immediately invited to attend Word Loaf, where Jonathan Franzen and Michael Chabon—both played by themselves—end up getting into a fight. And, everyone but Lisa goes on a hay ride.

Thinking about it, though, I wonder if I didn’t first hear about Bread Loaf in connection to the great American poet Robert Frost.

Do American kids in public schools still memorize his poems?

According to Frost biographer Jay Parini, it was in 1921, when “Wilfred Davison of Middlebury College founded the Bread Loaf School of English on the mountain campus of the college, twelve miles from the center of Middlebury itself.” And then five years after that when– at Frost’s suggestion– the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference was started by John Farrar, a New York publisher.

Parini writes that,

Frost once referred to the conference as the “Two Weeks Manuscript Sales Fair”—a sign that he resented the commercial aspects of the conference, which had been promoted by John Farrar.

These days the commercial side of the conference is much toned down—as the conference truly does feel like a celebration of all things literary.

And just as I’d imagined, Frost’s presence can be felt everywhere at Bread Loaf. His connection to “the mountain” has always been a huge part of Bread Loaf’s attraction to would-be writers~~~ including this would-be-writer.

I learned that a bit up the road, there is the interpretive nature walk, where his poems appear along the trail on signboards. And more than one faculty member, delivering their talk in the Little Theater would comment about feeling the ghost of Frost in this place. Frost did, after all, show up at Bread Loaf off and on for twenty years or more, living just down the road in Ripton—in the cottage where that muddy, boggy path through great clouds of mosquitoes and past orange-magenta mushrooms bright against the blue-green moss eventually led me.

The planned picnic that day had been rained out, but writers were assured that the cottage would be left unlocked for Bread Loafers between one and three that afternoon.

A man, who pointed the way, remarked that Frost’s mistress lived in the big white house at the foot of the hill.

Frost had bought the farm and moved in after the death of his wife. He lived down in the white house with his secretary and her husband—(an unusual arrangement) doing his writing maybe two hundred feet away up on a small hill in a small wooden cabin that smelled of long-ago fires in the fireplace.

2.

Robert Frost was already on my mind before I arrived in Vermont, since a few weeks before leaving for Bread Loaf, I was at the Sewanee Writers Conference in beautiful Tennessee. It really was a strange summer for me. At Sewanee, I attended an unforgettable lecture given by the newly appointed Oxford Professor of Poetry AE Stallings, who along with Camille Dungey are my favorite poets—and both were at Sewanee!

In her talk, Stallings spoke about “end-line rhymes.” She said “rhyme is a quantum entanglement of unrelated words.” It creates the terroir of the poem, she said. I really loved that idea.

She then shot an image up on the large screen behind her which showed a list of line-end words of a poem that, she promised, we would “immediately recognize.”

Know.

though;

here

snow.

queer

near

lake

year.

shake

mistake.

sweep

flake.

deep,

keep,

sleep,

sleep.

I am not very knowledgeable about poetry, so never expected to recognize anything. But suddenly my heart leapt as I instantaneously recalled the poem! Time-space dilation occurring as I found myself back in fifth grade, when my teacher read Robert Frost’s Stopping by Woods aloud to the class. We had to memorize the poem as well.

The immediacy of this experience reminded me a little bit of the way I could understand immediately the meaning of a Japanese sentence just at a glance. This only happened if the text was dense with kanji characters– but because you don’t sound out kanji like you do when reading a phonetic based script, you can grasp meaning in an instant. It is a different way of reading and understanding. And I was thrilled to experience it with AE Stallings.

On more than one occasion, I’ve been told by successful writers to stay as far away from MFA-style workshops as I could get.

And that, if I really want to learn how to write what I should do is copy out by hand my favorite novel.

“You have to write out the entire thing,” one of them told me. “You can’t imagine how illuminating it can be.”

I’ve never done this exercise myself, but I believe that I’ve experienced its intended effect doing literary translations. Translating a novel was a formative experience for me as a writer because I learned that writing is like any other art: while talent can’t be taught, technique can be learned.

While the novel never did get published in English, it was in working on the translation that I became fascinated—no, obsessed is the word!– with the “craft” of fiction.

This experience was without a doubt the start of my getting serious about learning how to write fiction. But other than the one failed novel translation, the majority of my experience with literary fiction was in poetry. Mainly, this was working on haiku referred to in academic papers on literature, as well as several Chinese poems used translating the subtitles of a documentary series on world heritage sites in China.

Without a doubt it was this work in poetry that lit up my imagination more than any other translation project I’ve ever done. You have to admit, it’s a daring thing to do: to translate a poem from one language into a poem in another. Even a poem of only three or four short lines in English can be something to fully occupy a person’s mind and heart. The challenge is great but so are the rewards.

Choices must be made. Something will always be lost.

Translation is always treachery!

Something I have started doing after Sewanee is to write out by hand the poems I love. Increasingly fascinated by meter and the slippery concept of the poetic line, I’ve been trying to just look under the hood of the poems I fall in love with. If a poet dispenses with rhyme and meter, what is the organizing form of the poem? How do the line breaks hold the form together?

George Oppen, for example, wrote that “the meaning of a poem is in the cadences and the shape of the lines and the pulse of the thought which is given by those lines;” while James Longenbach makes it simpler still when he says that “poetry is the sound of language organized in lines.”

4.

Logenbach’s “sound of language” immediately calls to mind Robert Frost’s idea of “the sound of sense.”

Jay Parini writes about Frost’s notion of “writing with your ear to the voice,” and how he singled out Wordsworth as a key predecessor:

“This is what Wordsworth did himself in all his best poetry, proving that there can be no creative imagination unless there is a summoning up of experience, fresh from life, which has not hitherto been evoked.”

Poets, like birders, are often praised for their extraordinary vivid sight –the way their poems evoke the details of how something looks. But for Frost it was always about the sound. In a fascinating lecture delivered in the Little Theater by literature professor Kamran Javadizadeh, he gave an analogy for the “sense of sound”: as a child he would listen to his parents speaking Farsi in their bedroom—and though he could not make out the words, the sense of what they were saying was usually clear enough. And that this is something that can be wonderfully captured in poetry—through rhyme and meter, and even in the construction of the poetic line.

The next day, I took an unforgettable class workshop on sound with Miciah Bay Gault (whose novel I am really enjoying). How can you evoke a crowded place not just in syntax but in ac long, crowded sentence with many commas. Or in breathless fragments connected by semi-colons. And, of course, by words that seem to teem and crawl. Toward the end of the class, she had us pick a bird and evoke the sense of the bird not only in the syntax of the sentences but in meter and the felt quality of sounds of words. Some of this is subjective but a lot isn’t.

Mine is not great but I had this:

In the time when young hawks learn to fly: again and again screeching, screaming, streaking past my kitchen window. A long hush falls across the bird feeder, finches hide in the lemon tree.

5.

After the long summer of three intense workshops back-to-back, I am surprisingly energized. I feel excited by the poetry of Robert Frost. But not just Robert Frost. I am lit up with all the sonic possibilities in my reading and also– with my writing.

I have read that during Confucius’ time, aristocrats wore jade pendants around their neck whose number was also prescribed by rank. When they walked around the halls, one could hear the bell-like tinkling sound of the jade pieces clinking against each other so that those of higher rank (who had on a greater number of pendants) could be heard louder than those of a lower rank (with less jade). This melodious sound 玲玲 (rei-rei), was called the “sound” of a virtuous person.

The sense of sound could be abstract like that. Like the sound of virtue. But Frost, I suppose was really trying to capture the sense of sound of the everyday.

A few months ago, I was walking around in the Huntington gardens in Pasadena when I saw a lone snail slowly making her way across the sidewalk, leaving a slimy trail in her wake.

When I was a little girl, I remember having to avoid the multitude of snails that appeared every morning on the sidewalks on my way to school. There were so many of them back then, and I used to love hopscotching around them to avoid accidentally harming one… But these days I can’t remember the last time I saw one. I’ve never seen a snail in our garden in Pasadena, though I suspect they are there based on all the little munch marks in my basil.

In this wonderful book called How to Speak Whale, there was mention of a tree snail in Hawaii that was supposed to make a beautiful sound. I think it’s just a legend but it’s incredible to imagine the forests reverberating with the song of snails!

How to evoke that sound in a poem?

++

Notes:

- I’ve had some discouraging experiences in writing workshops. I’ve written about my experiences in this essay at the Millions, called Culture Shock: Reassessing the Workshop. I was so worried that my three summer workshops (Lighthouse with Katie Kitamura in June; Sewanee with Vanessa Hua and Maurice Carlos Ruffin in July; and Bread Loaf with Jess Row and Sidik Fofana in August) would be disappointing as well. But nothing could be further from the truth. While it was not all great at Sewanee, I can say that this summer has me lit up in terms of reading and writing. I came back with so many new ideas for my manuscript as well as a long list of books to read, including these great recommendations: Anomaly, by Herve de Tellier; Theodore McComb’s incredible debut story collection The Uranians; Counterfeit by Kirstin Chen, People of the Book, by Geraldine Brooks (how did I never hear of her?), Loot by Tania James (I loved it!!) ; Eleanor Catton’s Birnam Woods; Jay Parini’s biography of Robert Frost; not to mention all the books by my teachers! I have been reading nonstop since I’ve been home (I loved Jess Row’s the New Earth and Sidikk’s Fofana’s Stories from the Tenants Downstairs!)

- The LARBs ran an essay about how the MFA program is not that bad… closer to my own thoughts was this lecture, given at Bread Loaf 2023, by Tiphanie Yanique. I also always liked Erik Hoel’s post on his Substack.

- A new book is coming out on soundscapes in writing called The Sound of Writing (John Hopkins Press)

- Other bad news was I missed the hay ride at Bread Loaf—because (to put it mildly) an unfortunate mishandling of a Covid outbreak. The fallout over it has already ignited much discussion online. Now that I am home, it looks like while Sewanee had followed the old pandemic protocol, Bread Loaf was following what we will be seeing going forward–limited contact tracing, limited public announcements, masking recommended not mandatory, etc.

- All the Bread Loaf talks were recorded—here is a place to listen.

- My report from Sewanee…

- About the sonic landscape: my review in the Rumpus of Kim Haines-Eitzen’s Sonorous Desert and my Substack post the Sonorous World (please consider subscribing!!)

NEVER AGAIN WOULD BIRD’S SONG BE THE SAME

He would declare and could himself believe

That the birds there in all the garden round

From having heard the daylong voice of Eve

Had added to their own an oversound,

Her tone of meaning but without the words.

Admittedly an eloquence so soft

Could only have had an influence on birds

When call or laughter carried it aloft.

Be that as may be, she was in their song.

Moreover her voice upon their voices crossed

Had now persisted in the woods so long

That probably it would never be lost.

Never again would birds’ song be the same.

And to do that to birds was why she came.

— Robert Frost